SOUTH PORTLAND — The Maine coast could become home to a pilot project to create the country’s first deepwater, floating wind farm.

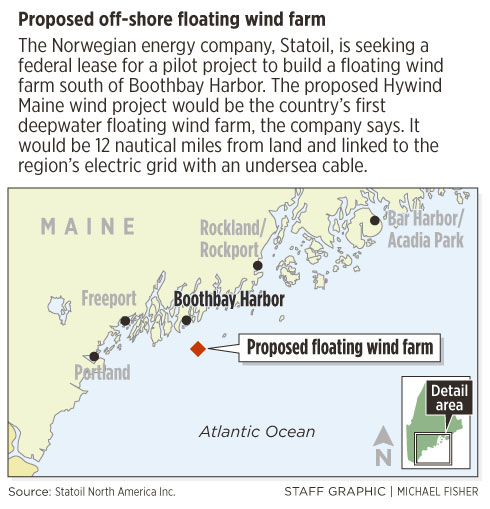

A task force formed by the federal Bureau of Energy Management met Thursday to consider a commercial lease for a test project on the outer continental shelf, roughly 12 miles from the nearest land, in deep water south of the Boothbay Harbor region.

If the four-turbine project wins approvals and the developer goes forward, it could be operating in 2016 and generate as much as 12 megawatts, equivalent to the power needs of about 18,000 homes.

The meeting was scheduled after the Norwegian energy giant Statoil North America Inc. filed an unsolicited application to the federal agency in October.

Statoil’s application is a major step for Maine’s ambition to create an offshore energy industry. Advocates say wind resources are better offshore, and the sites are far enough from land to minimize the visual impact for coastal residents.

“This is huge,” said Paul Williamson, executive director of the Maine Wind Energy Initiative. “If this goes forward and is built within the next five years, it would be the first commercial-scale floating project in the world.”

To go forward, Statoil will need timely permit approvals from various government agencies, and decide in pending studies that the project makes business sense, among other things. It also will have to conclude that Maine is the best place for a commercial test of the technology, which Statoil and other companies are exploring in other countries.

“This project would keep us in the game,” said Habib Dagher, the University of Maine professor who has led the state’s offshore wind power effort.

Statoil also will look for federal agencies to conduct an efficient review that doesn’t drag on indefinitely, he indicated. The bureau said it would make a decision in 2014.

“We don’t want the bureaucracy to get in the way of moving ahead,” Dagher said.

Maine has created a phased-in approach to developing floating offshore wind turbines.

It is starting with a small-scale test model off Monhegan Island in 2012, and demonstration projects generating as much as 25 megawatts by 2016 — equivalent to the power needs of roughly 37,000 homes. The Maine Public Utilities Commission issued a request earlier this year for demonstration projects.

The PUC has yet to disclose the outcome of that process, but a staff member said at Thursday’s meeting that the agency is negotiating with select bidders and may make an announcement in a couple of months. Statoil is among several companies that have made proposals.

Ultimately, the state is trying to encourage development of a commercial-scale wind farm with a capacity of 1,000 megawatts by 2020. Additional wind farms are contemplated by 2030, leading to what supporters say could be billions of dollars in investment for the state and supporting industries to manufacture, install and service hundreds of units. Statoil’s test project alone is valued at about $20 million, according to Dagher.

Statoil’s proposal, called Hywind Maine, could be a first step. In its application, the company says it ultimately wants to develop a full-scale project in the area.

That scenario depends in part on researchers being able to drive down the cost of producing power 20 miles offshore with turbines that float on the water, rather than being anchored to the seabed.

A UMaine study last year, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, concluded that in 2020 it will be possible to generate power in the 10-cent-per-kilowatt range, on par with conventional sources. The cost of producing power from Statoil’s four test turbines would be more than twice as much because it’s a small project, Dagher said, but by law the output can’t add more than a small fraction of a penny to utility rates in Maine.

Hywind Maine would have a capacity of 12 megawatts, generated by four, 3-megawatt turbines. According to Statoil’s lease application, the turbines would be tethered roughly 12 nautical miles from land in 460 to 520 feet of water. Good wind speeds have been measured in the area. The test site would be less than four square miles.

The turbines would be connected to substations by undersea cables. They could make landfall at a substation in Boothbay Harbor, said state Rep. Bruce MacDonald, D-Boothbay, a member of the task force.

During the pilot project, the power would feed into the region’s electricity grid. It remains unclear how Statoil will distribute or sell the energy if the project becomes operational as a commercial wind farm.

Fishermen and residents in the area have mixed views of the project, MacDonald said. Fishermen see the opportunity for other marine-related jobs, but they don’t want the turbines or cables to interfere with their boats or fishing grounds.

The need to maintain the turbines and platforms also holds the possibility for business development in the area, MacDonald said.

“It’s early days,” he said. “It’s still R&D. We don’t know if it will pan out.”

Statoil has identified an inshore location where the floating turbines could be assembled before being towed out to sea. Bath Iron Works has been working closely with off-shore wind advocates, as the shipbuilder seeks to diversify its business.

Statoil is testing a 2.3-megawatt floating turbine off the Norwegian coast. A similar test project was launched recently by an American company, off Portugal. Earlier this fall, Japan announced ambitious plans to build floating wind farms off Fukushima, to help replace the output of nuclear power plants that were destroyed by an earthquake and tsunami in March.

Send questions/comments to the editors.