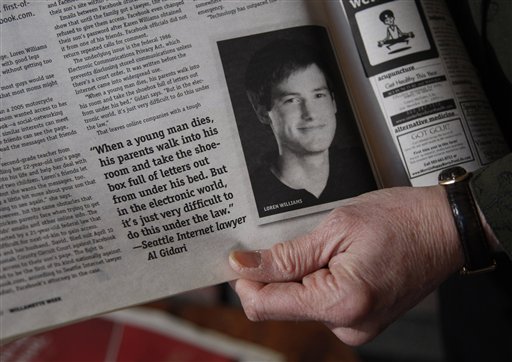

LINCOLN, Neb. — When Karen Williams’ son died in a motorcycle crash, the Oregon woman turned to his Facebook account in hopes of learning more about the young man she had lost.

Williams found his password and emailed the company, asking administrators to maintain 22-year-old Loren Williams’ account so she could pore through his posts and comments by his friends. But within two hours, she said, Facebook changed the password, blocking her efforts.

“I wanted full and unobstructed access, and they balked at that,” said Williams, recalling her son’s death in 2005. “It was heartbreaking. I was a parent grasping at straws to get anything I could get.”

Now lawmakers and attorneys in at least two states are considering proposals that would require Facebook and other social networks to grant access to loved ones when a family member dies, essentially making the site contents part of a person’s digital estate. The issue is growing increasingly important as people record more thoughts and experiences online and more disputes break out over that material.

Williams, a second-grade teacher from the Portland suburbs, ultimately got back into her son’s account, but it took a lawsuit and a two-year legal battle that ended with Facebook granting her 10 months of access before her son’s page was removed.

Nebraska is reviewing legislation modeled after a law in Oklahoma, which last year became the first state to take action.

“Mementos, shoeboxes with photos. That, we knew how to distribute once someone passed away,” said Ryan Kiesel, a former legislator who wrote the Oklahoma law. “We wanted to get state law and attorneys to begin thinking about the digital estate.”

Under Facebook’s current policy, deaths can be reported in an online form. When the site learns of a death, it puts that person’s account in a memorialized state. Certain information is removed, and privacy is restricted to friends only. The profile and wall are left up so friends and loved ones can make posts in remembrance.

Facebook will provide the estate of the deceased with a download of the account data “if prior consent is obtained from or decreed by the deceased or mandated by law.”

If a close relative asks that a profile be removed, Facebook will honor that request, too.

Like the Oklahoma law, the Nebraska bill would allow friends or relatives to take control of social media accounts if the deceased person lived in the state. The measure would treat Facebook, Twitter and email accounts as digital assets that could be closed or continued by an appointed representative.

Omaha lawyer William Lindsay, who specializes in estate planning, said his professional experience has taught him that the issue should be addressed in the law. But he also has a personal interest because of a cousin who died while serving in the Navy.

“We wanted to be able to get the email records, but we couldn’t because nobody knew the password,” Lindsay said. “We wanted to let her friends know she had died, but we didn’t know all of them.”

Sen. John Wightman, who sponsored the measure at the urging of the state bar association, said he expects the Judiciary Committee to approve the bill, sending it to the full Legislature.

Facebook spokesman Tucker Bounds said the company was surprised by the Oklahoma law and was working closely with Nebraska legislators on the latest proposal. The company declined to say how many people had requested access to accounts held by Oklahomans, but Bounds said it was relatively rare.

“I can tell you there aren’t people pouring out into the streets asking for access,” Bounds said.

Oregon could be the next state to take up the issue. The Oregon State Bar Association has formed a group to work on the matter and hopes to propose legislation next year.

Portland lawyer Victoria Blachly said the plan will mirror the Oklahoma law, but it will also include a “virtual asset instruction letter” that lists online information and passwords, along with instructions for when someone dies or becomes incapacitated.

“That’s the part that social media providers have been wrestling with,” Blachly said.

Like others, Blachly said she began studying the issue after a young relative died and left social media accounts in limbo.

Her top concern is the emotional value of social media accounts.

“Some people say ‘Well, if I get hit by a bus, what do I care?'” she said. “The people who love you care very much about it.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.