WASHINGTON — A world-class runner from the Penobscot Nation who some believe has been neglected in the annals of great Maine athletes is getting national recognition this summer on the 100th anniversary of his Olympic feat.

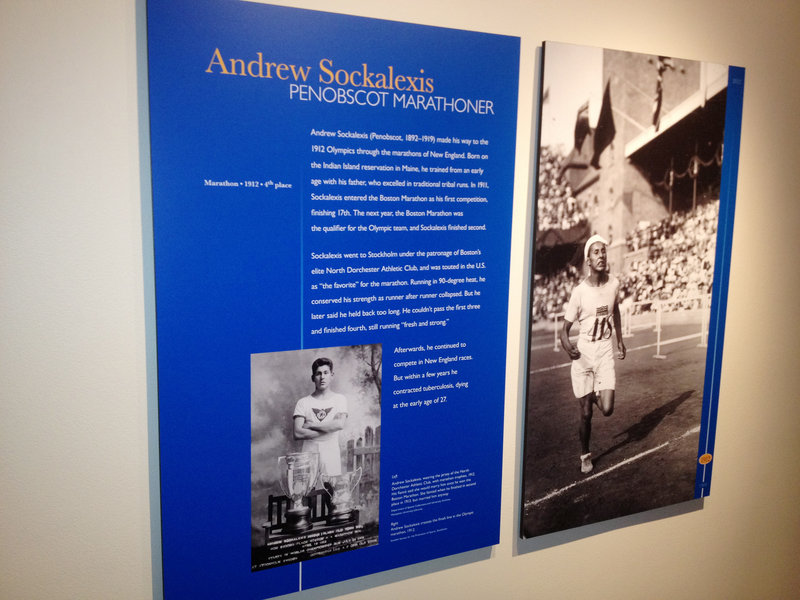

Andrew Sockalexis, who grew up on Indian Island in Old Town, is among five athletes individually profiled in an exhibit called “Best in the World: Native Athletes in the Olympics” on display at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

Sockalexis was just 20 years old and had been running in big-league races for about a year when he steamed across the Atlantic to compete in the 1912 Olympics held in Stockholm, Sweden.

As one of the original games held in every Olympics, the marathon was considered “the event” of the games, according to marathoner and Maine author Ed Rice. And unlike in other sports where Native Americans were barred from participating, running was an “open opportunity,” Rice said.

After finishing second at the 1912 Boston Marathon, Sockalexis was regarded as a major contender and potentially a favorite for gold in Sweden. He just missed the medal stand, however, by finishing fourth in a race during which half of the 68 runners never finished due to extreme heat. One participant died.

Rice, who has written a biography of Sockalexis, said he was a phenomenal, natural runner with enormous future potential. But Sockalexis had “slipped right off of the sporting pages” within several years after he contracted tuberculosis. He died in 1919 at age 27 and is buried on Indian Island.

“That 1911 Boston Marathon was his first official race. Can you imagine anyone today starting with the Boston marathon?” said Rice, author of “Native Trailblazer: Andrew Sockalexis — Penobscot Indian who followed the Maine running path to glory and tragedy.” “By the time of the 1912 Boston Marathon, he had only had four other marathons.”

Rice and Penobscot tribal members have suggested that both Andrew Sockalexis and his older cousin Louis Sockalexis often have been overlooked on lists of great Maine athletes.

Louis Sockalexis was the first Native American to play in Major League Baseball and is often credited with prompting his team, the Cleveland Spiders, to change its name to the Cleveland Indians.

A temporary exhibit at the National Museum of the American Indian, the “Best in the World” show pays special homage to the 1912 Games because of the significant role played by Native American athletes. The exhibit runs through Sept. 3.

The most exhibit space is devoted to Jim Thorpe, arguably the best-known Native American athlete. Thorpe was the first Olympian to win gold in both the pentathlon and decathlon that year — a feat that has yet to be repeated a century later.

Native Hawaiian Duke Kahanamoku also won gold, in the 100-meter freestyle, while Lewis Tewanima of the Hopi Tribe won silver in the 10,000-meter run.

“Although small in numbers, Native athletes were the third-largest medal-winning group in the large U.S. team,” the museum exhibit reads. “They became national and international heroes at a time when indigenous people sorely needed recognition.”

The exhibit also includes more than a dozen other Native American Olympians through the generations.

Washington Bureau Chief Kevin Miller can be contacted at 317-6256 or at:

kmiller@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.