WAHSINGTON – The idea behind Paul Ryan’s Medicare plan is to slow growing costs and keep the program more affordable for the long haul.

But it’s all in the details. The Republican-backed shift to private insurance plans could saddle future retirees with thousands of dollars a year in additional bills.

That would leave the children of the baby boom generation with far less protection from medical expenses than their parents and grandparents have had in retirement.

And there’s another angle consumers need to look at: Medicaid.

The GOP vice presidential candidate has also proposed to sharply rein in that program and turn it over to the states. Usually thought of as part of the safety net for low-income people, Medicaid covers nursing home care for disabled elders from middle-class families as well.

Medicare and Medicaid cover about 100 million people between them, touching nearly every American family in some way.

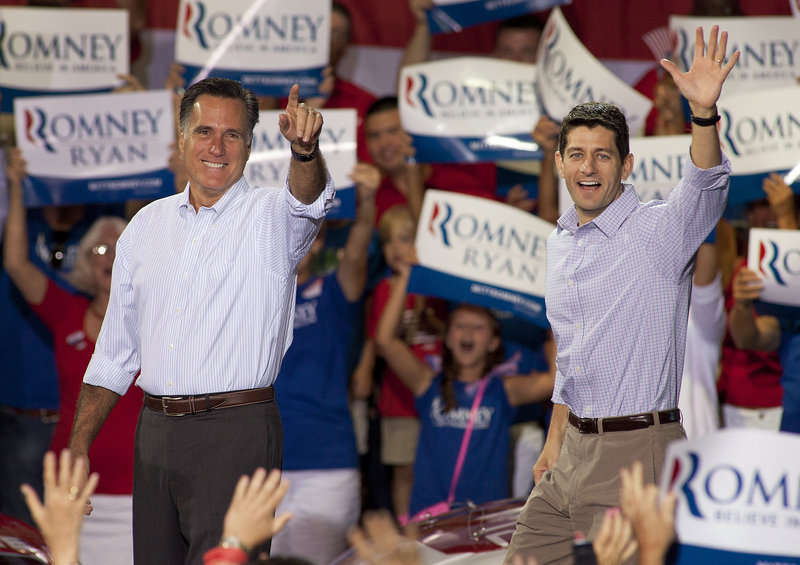

Pulling no punches, President Barack Obama’s campaign launched a new online video Monday attacking what it called the “Romney-Ryan” Medicare plan. It features anxious seniors and closes by accusing the Republicans of “ending Medicare as we know it” to pay for tax cuts for the wealthy.

Mindful of the risks, Romney is trying to put some distance between his agenda and the specifics of Ryan’s budget proposals.

In an interview Sunday on CBS’ “60 Minutes,” Romney and Ryan both offered words meant to reassure the elderly.

America is about more choices, Romney said, and “that’s how we make Medicare work down the road.” He said the program won’t change for seniors currently counting on it. Ryan pitched in that his mother is a “Medicare senior in Florida.”

In general terms, Romney has spoken of providing “generous” but undetermined subsidies to help future retirees buy private insurance, or let them have the option of traditional Medicare. He’s also endorsed a gradually increasing age to qualify for benefits.

During the Republican primary, Romney called Ryan’s budget a “bold and exciting effort” that was “very much needed” but held back from a full embrace.

Ryan, a conservative Wisconsin congressman and chairman of the House Budget Committee, calls his Medicare plan “premium support.” Future retirees would get a fixed amount to use for health insurance. Democrats call it a voucher plan.

In theory, Ryan’s plan could work, economists say. Instead of Medicare just paying all the medical bills that come in, the fixed government payment would limit how much taxpayer money flows into the program. That would force everyone, from individual retirees to the biggest hospitals, to watch costs.

Ryan has issued two versions of his plan with Democrats, showing it has some bipartisan appeal. But the versions passed by the House have had a hard partisan edge.

The devil’s in the details. And there are lots of them that have yet to be ironed out.

“From the standpoint of public understanding, the Romney-Ryan ticket has a hill to climb,” said health economist Joe Antos of the business-oriented American Enterprise Institute. “I think they can do it, but it’s going to require some explaining. I think there are a lot of independents who are going to be nervous.”

For the most part, Ryan’s plan would not directly affect people now in Medicare. One exception: In repealing Obama’s health care law, Ryan would re-open the Medicare prescription coverage gap called the doughnut hole.

Under his plan, people now 54 and younger would go into a very different sort of Medicare. Upon becoming eligible, they would receive a government payment that they could use to pick a private insurance plan or a government-run program like traditional Medicare. The payment would be indexed to account for inflation, and that could be a problem if health care costs race ahead of the inflation rate.

The private plans would be regulated by the government, and low-income people, as well as those with severe health problems, would get additional assistance. People who pick plans with relatively generous benefits would pay more out of their own pockets.

Ryan would also gradually raise the Medicare eligibility age from the current 65 to 67.

Backers say the result of his Medicare plan would be a more affordable and sustainable program, both for taxpayers and beneficiaries. Currently, Medicare’s giant trust fund for inpatient care is projected to run out of money in 2024.

But critics see a massive cost shift to beneficiaries.

“The only way to drive real savings is to set a lid on the growth in the voucher,” said Democratic economist Judy Feder. “That most likely means shifting costs to beneficiaries, not controlling costs.”

In an analysis earlier this year, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office said some of the effects of Ryan’s plan “would of necessity be a great deal stronger” than current law, which includes Medicare cuts in Obama’s health care law yet to take place.

Under the most likely current budget scenario, Medicare spending for the typical 66-year-old would rise to $9,600 in 2030, or about 75 percent more than now, the CBO projected.

But under Ryan’s plan, spending would rise more slowly to $7,400, or about 35 percent more than current levels.

That difference would result in a cost shift of thousands of dollars to individual retirees, critics say.

Under the previous version of Ryan’s plan, a typical 65-year-old retiree would have been responsible for about two-thirds of his or her health care costs in 2030, according to the budget office. That translates to a cost increase of $6,350 a year, says the Obama campaign.

The political sensitivities are clear. Polls find that Americans lean heavily on Medicare to help keep them secure after retirement and are suspicious of proposed alternatives, such as Ryan’s. Surveys also give Democrats an edge over Republicans when people are asked which party people most trust to handle Medicare. Democrats held a 48 percent-39 percent advantage on that issue in a June 2011 AP-GfK poll.

“This puts Medicare in play as a central issue in the campaign,” said John Rother, president of the National Coalition on Health Care, a nonpartisan group representing a broad swath of players in the health care system.

Send questions/comments to the editors.