After Joe Biden tripped up his boss by voicing support for same-sex marriage while the president remained on the fence, speculation was rampant about whether the remarks were spontaneous or deliberate.

But to those who know Biden, there was no doubt. He was just speaking his mind.

“That’s what you get,” said John Marttila, a political strategist who worked alongside Biden in his first Senate campaign, and many others since. “You never have to worry, you never have to ask yourself the question, is this politician really telling me what he cares about, what’s on his mind? Not with Joe.”

Biden long has cast himself as a regular guy, who still relishes wading into a crowd or taking a microphone, searching for a way to connect with middle-class voters who remind him of his own Scranton, Pa. roots. He is the intensely devoted family man, prizing relationships strengthened by tragedy and turmoil that reconfigured a life of sometimes extraordinary luck.

But this is also the Joe Biden who is known for strong opinions grounded in experience and study, as well as the self-regard that makes him a wild card.

Biden took on the vice presidency after a 36-year Senate career he hoped would lead to the Oval Office. Instead, his assignment over the last 3 1/2 years has been to figure out a role in a White House where he is a junior partner despite his seniority, a well-known member of the establishment grafted to a team that promised to change politics as we know it. His job, which comes with few clearly defined responsibilities, has been to provide value to Obama, while staying true to himself.

It has not always gone smoothly, largely because of Biden’s well-known tendency to speak out loud and at length. But he has settled into the vice presidency while holding tight to the touchstones of his identity.

“There’s no delusions of grandeur. He’s not president. … Before Joe went into that situation, he had to resolve that in himself,” said his sister, Valerie Biden Owens, a political confidant since she managed his first campaign for a county seat in Delaware.

Biden has emerged as a very different vice president from predecessor Dick Cheney. He has worked hard to make his case on issues from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to the pursuit of health care reform, while accepting his place in a hierarchy that gives him the president’s ear, but not his decision-making power.

To understand Biden as vice president, though, requires knowing the journey that shaped him and brought him to this point. It began in a wood-frame house on Scranton’s North Washington Avenue, steps from the last stop on the streetcar line. In the Biden house, every Sunday started with Catholic Mass and ended with family, the younger ones listening in as the older men hashed out politics around the kitchen table.

MIDDLE-CLASS GUY

As the administration’s frequent ambassador to white, working-class voters, Biden has waxed so often about growing up in 1950s Scranton, the stories have taken on the gloss of fable. In a June speech, he joked that Obama had latched on to the theme, in a way that “makes me sound like I climbed out of a coal mine in Scranton with a lunch bucket.”

In fact, Biden, who turns 70 in November, grew up in a solid, middle-class neighborhood. Even so, his parent’s decision to move in with his grandfather when Biden was 5 was a step backward. Biden’s father had done well as a manager for a company servicing merchant marine ships. Then he lost his savings in a pair of business ventures, including one with a partner who ran off with the money. Scranton offered refuge.

Biden’s father found work cleaning boilers and selling pennants, before eventually managing a car dealership.

“My dad, Joseph Robinette Biden Sr., was a man of few words. What I learned from him, I learned from watching,” Biden wrote in his 2007 autobiography. “He’d been knocked down hard as a young man, lost something he knew he could never get back. But he never stopped trying … Get up! That was his phrase, and it has echoed throughout my life.”

Biden and his friends spent their days in Catholic school, returning home to waiting mothers before heading out into the neighborhood’s ball fields and woods.

The Biden household was a gathering point, welcoming various uncles and the friends of Biden’s grandfather. When Joe Biden’s family moved again to the suburbs of Wilmington, Del., the family drove back nearly every weekend.

“I remember distinctly as not having any feeling like he left,” says a Biden childhood friend, Tom Bell, now an insurance agent in the Scranton area.

Biden’s family and friends recall him as a leader. Bell recounts that after a neighborhood bully picked a fight, friend Charlie Roth called Biden, then 12 or 13 and living near Wilmington. When the Bidens returned the following weekend, Joe beat up the bully on their behalf, Bell says.

Joe Biden went on to the University of Delaware. On spring break of his junior year, he and a group of friends ended up in the Bahamas, where Joe met Neilia Hunter, a senior at Syracuse University. Smitten, he applied to law school at Syracuse so they could be together. The couple married and moved to Wilmington, where Biden accepted a job as a corporate lawyer. But he quickly became disillusioned representing companies and left for a job with the public defender’s office, practicing civil law part-time.

His boss took him along to Democratic political meetings and Biden was invited to run for a county council seat, representing a majority Republican district. Biden didn’t even know where the council met, but he ran and won in 1970. The following spring, he was asked to help recruit a candidate to run against Cale Boggs, a Republican former governor and congressman seeking his third term in the U.S. Senate.

On a summer morning in 1971, the 28-year-old Biden was shaving in a Delaware motel room when he heard a knock on the door. A pair of state Democratic leaders, one of them a former governor, barreled in. Biden, standing in his underwear with shaving cream cupped in his hand, worried he’d gotten himself into some sort of trouble.

We think you should be our Senate candidate, the men told him. Biden’s first thought: Was he even old enough under the Constitution to take the oath of office?

“When you’re from a small state, you’ve got to be extra good because everybody knows you,” said Henry Topel, the party chairman who was one of the two men who asked him to run. “I was extremely impressed with Joe. He was a phenomenal orator … and above all he knew his subject and he certainly knew the road he was on. He was a young shining star.”

SENATE YOUNGSTER

Early polls showed Biden running far behind.

“I’ve been following politics for 40 years and there’s never been a race in 40 years that was as much of a longshot as this,” said Ted Kaufman, a volunteer in that campaign who became Biden’s long-time chief of staff before being appointed to serve out his final Senate term. “I told him he couldn’t win.”

Biden’s shoestring campaign, headed by sister Valerie, cranked out weekly brochures on newsprint delivered by volunteers to nearly every Delaware home. Playing off the state’s size and the candidate’s knack for connecting with voters, the campaign leapfrogged to living room coffee gatherings, often six or seven in a day, attended mostly by housewives. Biden campaigned alongside his wife, sometimes with their three young children in tow.

“He presented himself the way he was. There’s no daylight between the private person and the public persona and there hasn’t been with Joe,” his sister said.

Pitted against a popular incumbent, Biden took to opening his suit jacket to reveal a button on the inside of the lapel that said “I like Cale,” putting voters at ease, said Ron Williams, who covered the race as a reporter for the Wilmington News-Journal.

Biden won by a little more than 3,000 votes. He turned 30 little more than a month before being sworn in, making him one of the youngest people ever elected to the Senate.

Weeks later he was in Washington to hire staff, leaving his wife in Delaware to shop for a Christmas tree. The office phone rang and Valerie picked up. “When she hung up the phone, she looked white,” Biden wrote.

Neilia Biden was dead, killed in a car accident along with the couple’s year-old daughter, Naomi. Biden’s two sons were critically injured.

In a speech this past May to families of U.S. soldiers killed in action, Biden recalled how the tragedy plunged him into anger and depression.

“For the first time in my life, I understood how someone could consciously decide to commit suicide,” he told the group.

“I remember being in the Rotunda, walking through to get to the plane to get home to get to identify (the bodies) … I remember looking up and saying ‘God … you can’t be good. How can you be good?'”

Biden’s sister moved in to care for her nephews. Biden told family and friends he would take a pass on the Senate.

But Majority Leader Mike Mansfield and others pleaded with Biden to give the job six months, with colleagues urging him to immerse himself in his work. Kaufman recalls days when Biden seemed fine, and then the next “it’d be every bit as bad as the first day. He’d just be coming in like he’d been blown away.”

Biden found a comfort zone in Washington by maintaining one outside it, taking Amtrak home to Wilmington each night to be with his sons. In the Senate, he became a student and observer of storied figures like Mansfield and Hubert Humphrey.

“He’s a very hierarchical guy,” Kaufman said. “His basic approach was I’m junior, they’re senior. … He was very comfortable in giving deference to the senior members.”

In 1975, a friend passed him the phone number of Jill Jacobs, an aspiring teacher eight years his junior, and the two began dating. But Biden proposed six times before she agreed. They married in 1977.

By 1980, Biden had built a reputation in the Senate as a comer, with some people encouraging him to think about a future run for the presidency, though he was not yet 40. In his book, Biden writes that he resisted because he could not yet answer a question posed by Marttila about why he wanted to be president.

With Ronald Reagan nearing the end of his second term, Biden decided the time might be right. He traveled the country as a candidate in 1987, still little known outside Delaware. That changed after Reagan nominated conservative judge Robert Bork to the Supreme Court to replace retiring moderate Lewis Powell. The nation’s attention turned to the Senate Judiciary Committee and its chairman, Biden.

MISTAKES MADE

By late summer, Biden was dividing his time and energy between stumping for the presidency and preparing to lead hearings on Bork, whose nomination drew heated opposition from liberals. The two sides of Biden’s political life collided as the hearings began, with newspaper reports that, during an Iowa debate, he had plagiarized a speech by British politician Neil Kinnock. Then came allegations that, while at Syracuse, Biden had inserted large parts of a law review article, without attribution, into a paper he wrote.

Biden admitted making mistakes, but insisted it would have no effect on his candidacy. Days later, he withdrew from the race and called Judiciary Committee colleagues into a private meeting.

“He was devastated. It was a hammer blow to the gut,” said former Sen. Alan Simpson, R-Wyo., who was in the room. “He called us in and he said ‘I’m very hurt, I’m embarrassed and I think if I’ve brought any embarrassment on any of you … I’d be glad to step down. It was very dramatic. There wasn’t anything contrived. It was just silence.”

The silence was broken by Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., followed by other senators, noting that at one time each of them had made mistakes. They urged Biden to stay on. He did, presiding over hearings that led to Bork’s rejection, but were praised for maintaining a respect that allowed all sides to air their views.

Biden has said he viewed the Bork hearings as the beginning of a vindication. But his record four years later in presiding over the controversial nomination of Clarence Thomas — hearings charged with accusations of racism and sexism — remains the target of fierce criticism. While Biden writes about the Bork hearings at length in his book, he never mentions the Thomas confirmation.

During Biden’s short-lived pursuit of the presidency, Marttila recalls, he’d been concerned when a staffer mentioned Biden was popping 10 Tylenols at a time. But the headaches went overlooked in the blur of campaigning. In early 1988, though, Biden collapsed in a Rochester, N.Y., hotel room after a speech. Doctors discovered an aneurysm below the base of his brain.

His survival and recovery left Biden feeling that he’d won a second chance, sharpening his sense of priorities.

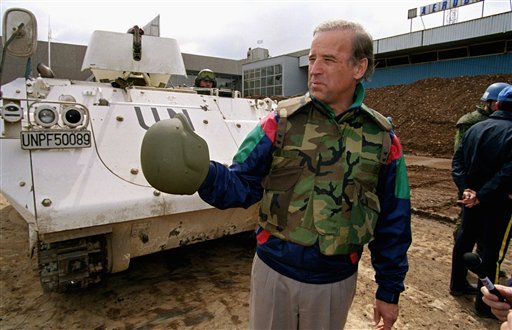

Back in the Senate, he pushed to increase funding for prosecution of domestic violence and sexual assault, and assistance to victims, winning passage of legislation in 1994 that became law. He also became an increasingly outspoken leader on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, urging Presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton to intervene in the wars splitting the former Yugoslavia.

After backing the second President Bush’s decision to send troops into Iraq, he became a critic of the war and the administration. But, as Biden did with the Balkans, he accompanied his rhetoric on Iraq with engagement, drawing up a proposal for a “soft partition” of the country into three ethno-religious regions and meeting with Iraqi leaders and military commanders. When Biden traveled to Iraq as vice president late last year before the U.S. pullout, it was his 16th trip to the country.

But after seeing Bush win a second term in 2004, he began to think anew about seeking the presidency.

COMMITMENT FROM OBAMA

In a 2008 primary season dominated by Democrats Barack Obama and Hillary Rodham Clinton, Biden got little traction among voters or political donors and dropped out after a poor showing in the Iowa caucuses. But his debate performances won praise, including from his opponents, and he was talked about as a candidate for secretary of state in a Democratic administration.

Instead, when Obama became the nominee and asked Biden to join the ticket, the Delaware veteran agreed on one condition.

“I said I want a commitment from you that in every important decision you’ll make, every critical decision, economic and political as well as foreign policy, I’ll get to be in the room,” Biden said in a late 2008 television interview.

Obama turned to Biden early, asking him to oversee administration of the $787 billion in economic stimulus money approved by Congress. Though Obama came to Washington opposing the Iraq war Biden initially supported, the vice president’s deep knowledge of the country made him a natural point-man in the administration’s dealings with Iraqi leaders, as well as defender against critics of the U.S. withdrawal.

Still, the agreement left important questions unsettled, with “a lot of uncertainty” about how Obama intended to use his vice president, Biden’s former chief of staff, Ron Klain, said in an interview with The Associated Press in late 2010.

While Obama asked for Biden’s opinion, he made key decisions that were at odds with that advice. Biden, for example, advised that the country’s financial condition was too shaky to pursue health care reform, but Obama moved ahead.

Yet when Obama signed the Affordable Care Act into law in March 2010, Biden was emphatic in recognizing the achievement and offering congratulations. He was caught on an open microphone proclaiming the legislation a big deal, with an expletive inserted for emphasis.

Biden also was the administration’s most strident opponent of proposals to sharply increase the number of U.S. troops in Afghanistan. Obama wound up dispatching 30,000 additional soldiers, but his decision to do so quickly and to set an end-date for most U.S. military involvement in Afghanistan has widely been seen as evidence of Biden’s influence.

Biden “played a very important counter-role to the generals,” said Jules Witcover, a veteran political journalist who wrote a 2010 biography of Biden.

“Although you could say Biden lost that fight,” because the additional troops were deployed, “in the long run he has prevailed, or is in the process of prevailing, with the combat troops coming out of Iraq and the movement toward getting out of Afghanistan,” Witcover said.

Biden also has shown a willingness to give his boss credit, even when his advice has been rejected, mostly notably after he urged Obama not to go ahead with the U.S. military raid that killed Osama bin Laden. When the raid succeeded, he praised the president’s resolve and decisiveness.

The relationship between Obama and Biden has worked, say those who know them, because Obama is comfortable hearing the vice president’s counsel, but also because of Biden’s embrace of his role as adviser rather than top decision-maker.

“They’ve been through a lot together and there’s a lot of mutual respect there,” Kaufman said. “The secret is Obama’s stood by the deal and Biden’s stood by the deal.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.