MEDWAY — Mike Michaud leaned into a table at a roadside diner and quietly sipped coffee.

It was mid-afternoon — halfway between the lunch and dinner rushes — and the wood-paneled dining room was motionless except for an attentive waitress, who regularly topped off the congressman’s cup.

Michaud’s sixth congressional campaign was suddenly in full swing. After a month of soft-selling his bid for re-election, Michaud entered October with a bang. Four debates against Republican challenger Kevin Raye had just been announced, and Michaud’s schedule was booked solid.

During the previous six months, the five-term Democratic incumbent maintained a comfortable, double-digit lead in the polls, but it was clear he didn’t intend to rest on his laurels.

Except for the moment.

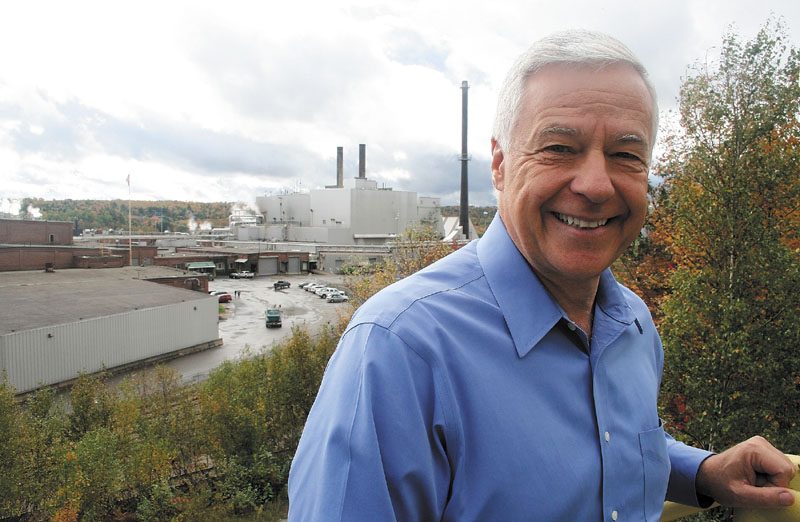

The 57-year-old had an hour to spare before he made tracks for his next appearance — a documentary screening in Waterville. By day’s end, the silver-haired Democrat would log more than 300 miles. He attended a new charter school opening in Fairfield, toured an adult learning center in East Millinocket, doubled back to Waterville, then spent the night in Portland before jetting back to the nation’s capital for a hearing with the American Legion.

The hearing was clearly on his mind.

Michaud is leading the charge in Washington to enforce compliance with the Berry Amendment, a provision that requires American service members to wear U.S.-made clothing, but allows an exemption for athletic footwear. In recent days, Michaud learned that some soldiers are also wearing boots made in China.

The thought doesn’t sit well with Michaud and he faults the White House for not closing the loopholes. Recently, President Barack Obama announced a $40 million challenge grant to bring jobs back to the United States, but Michaud proposes an easier solution.

He lightly thumped his hand on the table to emphasize his words.

“If the president really means what he says about bringing jobs back here to the United States, here’s a way he can do it,” he said of the Berry Amendment. “It’s good that he’ll spend money to try to bring jobs back here, but why doesn’t he have the secretary (of defense) comply fully and have our soldiers dress head to toe in American-made clothing? That wouldn’t cost a penny.”

Jobs and the economy are cornerstones for each candidate’s campaign in the 2nd Congressional District. Raye is focusing on Maine’s small businesses, while Michaud has touted its manufacturing.

It makes sense that Michaud would rally for factories, because they’re among the things he knows best.

Millworker mentality

For 29 years, Michaud was employed by the Great Northern Paper mill in East Millinocket.

In Millinocket and the surrounding towns, Michaud is a living legend. A trail system alongside Millinocket Stream bears his name, as does a classroom in nearby Katahdin Region Higher Education Center.

“Normally, they wait until you’re dead and gone before they name something after you,” Michaud joked.

Even during the 2010 election, when being a Democrat was suddenly a liability in Maine and elsewhere in the country, East Millinocket voters turned out for Michaud in a big way. Districtwide, Michaud beat his Republican challenger by only 10 percentage points, but in East Millinocket Michaud won by 37 points.

Michaud was born in Millinocket in 1955, and was raised alongside four brothers and a sister in Medway. He was a typical kid — fishing in the summer, tobogganing in the winter and helping out on his neighbor’s farm.

After graduating from Schenck High School, Michaud joined the ranks of millworkers at Great Northern Paper, instead of continuing his education.

“It was the school of hard knocks,” Michaud said. “Back then, that’s what people did. You’ve got generations after generations that went to the mill — from the time when they built the mill, pretty much until the 1980s.”

At age 25, pollution inspired Michaud to enter state politics. About 10 miles downstream from Great Northern, near his childhood home, a cove in the Penobscot River was a collection point for pollution.

“You could practically walk across the cove because of the sludge from the very mill I worked at,” he said. “Rather than sit back and complain about it, I decided to run for the legislature.”

Finding the middle

Michaud beat a veteran politician for a seat in Augusta and was soon appointed to the Energy and Natural Resources Committee. Michaud joined the committee along with state Sen. Ron Usher, who worked for S.D. Warren — a paper mill in Westbrook.

The pairing displeased many people, Michaud recalled.

“Here you had these two paper industry guys chairing the environment committee, and I remember the environmental groups and the editorial boards just went berserk, because they thought we were going to rape the environment,” he said.

At the same time, Michaud risked jeopardizing his relationship with his community by fighting for higher environmental standards at the mill — the lifeblood of the local economy and his bread and butter. It was a tricky proposition, but he never lost support from his coworkers or neighbors, said Stephen Stanley, a friend of Michaud’s since childhood and a coworker at the mill.

“If anybody was upset with him, I wasn’t aware of it,” Stanley said. “He got the river cleaned up. The pollution on it was as thick as a cake. You couldn’t hardly get a boat into it, but he got it cleaned up.”

Michaud said having a stake on both sides of the issue eased the political process during that time.

“My father worked there for 43 years and my grandfather before him for 40 years. Everyone in the family — four of my brothers, my sister — everyone worked in the mill at one point in time, and most of them for a lifetime. So everyone knew I felt strongly about jobs and the economy,” he said. “But, even with that, you can still have a balance. You have to have a balance between jobs and the environment and, by and large, both can go hand in hand.”

Michaud cites the passage of a forestry practices bill in 1989 by the state Legislature as a prime example. Months before the bill’s passage, Michaud was approached by two competing forces.

“The Forest Products Council came to me and said they wanted me to sponsor their forest practices, and I told them I would. Then the Audubon Society came to me and wanted me to sponsor their bill, and I told them I would. So I was the primary sponsor of both bills. I brought both groups in and said, ‘We’re going to pass something this year, and I want to work together.’ It took a lot of time, but we passed something,” he said.

The forestry act wasn’t beloved by either group, but it was a fair compromise and it’s had staying power, Michaud said. More than 20 years later, the act is almost identical to what was originally passed. Laws that don’t incorporate compromise from the very beginning are eventually reworked.

Michaud said he prefers to strike the right balance from the start.

“I’ve always taken the approach of sitting down, figuring out where people agree and disagree and finding ways to come closer together,” he said.

Looking at issues

Michaud’s critics have tried to paint him as a rubber stamp for the Obama administration, a claim he shrugs off.

“It’s politics. They’ll say I voted with the president 96 percent of the time, or whatever, but the way I look at issues is, ‘How can we change things for the betterment of Maine?'” he said.

Michaud said he’s keeping a close eye on the administration, particularly on trade issues.

In September, Michaud traveled to the New Balance shoe factory in Norridgewock with U.S. Trade Representative Ron Kirk, in an effort to draw attention to the importance of maintaining tariffs for overseas footwear.

As of last week, Kirk had given no indication as to whether tariffs would remain, Michaud said.

The Berry Amendment is also an open question. Last March, Michaud discussed the issue with Obama directly.

“I still haven’t heard back from the president,” he said. “I’m not too optimistic that he’s going to do anything.”

On Oct. 3, during the hearing with the American Legion, Michaud announced that he had joined forces with U.S. Rep. Duncan Hunter, R-Calif., to build bipartisan support for strengthening the amendment and to apply pressure on the Department of Defense.

“We all remember the outrage this summer when it was discovered that our Olympic athletes were wearing uniforms made in China,” Michaud said at the hearing. “Well, I think we should be as equally outraged about the fact that our troops are not wearing 100 percent American-made uniforms. Our soldiers put their lives on the line for us, and they should fight in uniforms they can trust, uniforms made in the USA.”

Working the crowd

Michaud recently paid a visit to the Katahdin Region Higher Education Center in East Millinocket.

The school’s director, Debora Rountree, said Michaud helped round up funding for the school and nine others just like it. The school, which is its 26th year, serves up to 300 students annually. It receives some funding from the state and is part of the University of Maine System.

During periods of layoffs at Great Northern Paper, unemployed workers flock to the center, Rountree said. The average age of mill employees is 50 and when those workers are suddenly out of a job, starting a new career is difficult. The school, which offers certificate, associate, bachelor and master’s programs, is meant to give former mill workers a leg up, she said.

Although the school is serious business, a group of staffers gather around the congressman as he strolls the building. Soon, the conversation veers toward upbeat news in the region: The mill is in the midst of a mini-boom.

In recent months, Great Northern has produced nearly 3,000 tons of paper for the best-selling erotic book series Fifty Shades. Just a year earlier, the mill had been closed for several months.

Michaud blushed slightly at the mention of the books, but he’s in his element in the growing crowd. He’s a people pleaser and a charmer, shaking hands with everyone he lays eyes on. As Rountree took Michaud on a tour of the school’s interactive classrooms, he quickly shook hands with every student.

In the school’s child care facility, however, Michaud encountered a less cheerful constituent.

Laura Barrows, the child care coordinator, was sitting on the floor cleaning when Michaud walked in. Barrows explained that she provides care for 20 children, has another nine kids on a waiting list and the program is stretched too thin.

“We don’t have enough funding, quite frankly,” she said.

Michaud listened intently for nearly 20 minutes as she spelled out the center’s growing list of needs. At the end, Michaud gave her a reassuring look and sincerely asked her for a list of the items, which she said she would gladly provide. When he said goodbye, he thanked Barrows for her time.

“Oh, you can stay,” she said. “You can help clean, that’s no problem.”

Michaud laughed.

Ben McCanna — 861-9239

bmccanna@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.