SEATTLE – In the early days of the fight for same-sex marriage, circa 2004, supporters in states across the country found themselves mostly alone and largely outgunned — scrambling to counter opponents’ messages at a time when barely a third of the country was on their side.

The re-election of President George W. Bush that year coincided with approval of constitutional bans against gay marriage in 11 states.

Less than a decade later, organizers of gay marriage campaigns in Washington and three other states speak of America’s growing embrace, of key endorsements they’ve won and broad coalitions they’ve formed.

And the four campaigns are doing something else they’ve not done before: They are working more collaboratively, picking through the debris of past defeats while looking to national gay rights groups for guidance.

It’s a coalescence that campaign insiders say reflects a maturing of the movement — one that stands in contrast to a time when the national groups failed to work together strategically.

In Maine, Maryland and Washington, where voters will be asked to approve or reject gay marriage, and in Minnesota, where they will decide whether to amend their state constitution to ban it, campaigns are hitting the homestretch in a nail-biter of an election cycle, each hoping its state campaign will be the one to end a 31-state losing streak that has plagued gay marriage at the ballot box.

“This is a priority for our community,” said Fred Sainz, spokesman for the Human Rights Campaign, one of the nation’s largest gay rights organizations.

Washington United for Marriage and the campaigns in Maryland, Maine and Minnesota together have raised more than $25 million and are joining ranks against a lone but formidable opponent — the National Organization for Marriage — and its political director, Frank Schubert.

At the same time, the Human Rights Campaign and another major national gay rights group, Freedom to Marry, have embedded staff in the state campaigns and are providing them with money and strategic support to avoid past pitfalls.

Zach Silk, campaign manager for Washington United, which is leading the effort to preserve same-sex marriage in this state through Referendum 74, said the opponents have built on their experiences each time — and it’s paid off for them.

NOM “has done a good job of learning lessons from every campaign and applying those lessons to the next one — and you can see it. The messaging is consistent,” Silk said.

“Our side has not had that: California was different from Maine was different from North Carolina.”

Evan Wolfson, executive director of Freedom to Marry, said the idea is to bring cohesion to the message that allowing committed gay and lesbian couples to marry helps families, while hurting no one.

“We learned a lot over the years as we battled the anti-gay attacks in several states,” Wolfson said.

“When we see the opposition run an effective ad” or use scare tactics to shift the conversation away from marriage, “we flag it for the others right away.”

But Schubert, architect of campaigns that defeated gay marriage in California in 2008, in Maine the next year and in North Carolina earlier this year, said his opponents are not seeing the bigger picture: that legalizing same-sex marriages isn’t just about them.

“In Washington, the backers of Referendum 74 appear to expect that voters will set aside the totality of human history and instead consider the issue through the prism of the present-day demands of gay activists,” he said.

“Their narcissism is their fundamental strategic failing.”

If you had to pick the state where gay marriage has the best shot of winning Nov. 6, it would most likely be Washington.

Three years ago, voters here became the first in the country to advance same-sex recognition by voting to keep the state’s domestic-partnership law intact.

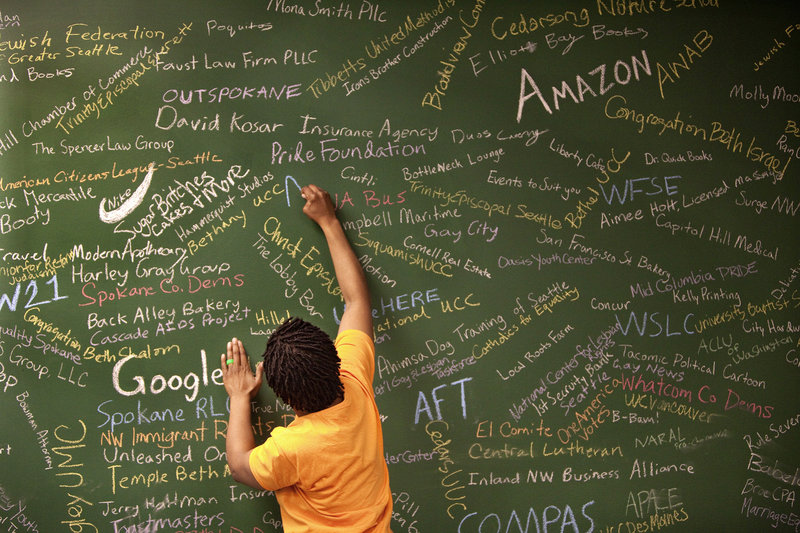

Long before that, however, advocates had begun building a coalition of support among business, labor, faith and other organizations. Today those same groups, along with dozens of new ones, make up the 500-plus partner network helping to get the campaign’s message out.

Campaign managers in Minnesota, meanwhile, have had far less time to build a base of support and make a case against a constitutional ban.

The Minnesota Legislature placed the ban on the ballot a year and a half ago, early in its session last year. Richard Carlbom, campaign chairman of Minnesotans United for all Families, said his group has since amassed a network of some 670 partners that include business, labor, faith and other organizations.

And while hopeful, he is mindful of the odds: Voters in 30 states have voted to ban gay marriage in their state constitutions.

Recent public polls on the issue haven’t favored his side. “Minnesota is trying to do something that no state has ever done before,” Carlbom said, referring to those losses. “We realize victory will be narrow.”

As the four states analyze the movement’s past mistakes, they are paying particular attention to the $40 million Proposition 8 defeat four years ago in California.

Passage of that constitutional ban on gay marriage only six months after a state Supreme Court ruling legalized such unions shocked the nation — and the post-mortems continue even to this day.

Critics say the same-sex-marriage campaign grossly underestimated its opponents and allowed them to define the message of the debate: that legalizing gay marriage would force schools to teach kids about it.

At the same time, the pro-gay message was fragmented and unfocused, with that campaign delaying by more than two weeks — an eternity in a campaign season — its response to ads about the consequences of gay marriage on children.

One of the more memorable anti-gay-marriage spots became known as the Princess ad, featuring a girl telling her mother what she learned in school that day: “that a prince can marry a prince and I can marry a princess.”

Silk said that this time around, his side has a series of ads ready to run aimed at directly and immediately countering opponents’ ads they find most distortive and misleading.

Both sides have aired ads in all four states.

In Washington, the first ad reminds voters that gays and lesbians already have all the benefits of marriage and that you don’t have to be anti-gay to reject gay marriage. It hits on a central theme of NOM’s campaign: that marriage is a union of one man and one woman and there are consequences to redefining it.

The ads of same-sex marriage supporters have featured mostly heterosexual couples and individuals talking about the benefits of marriage.

Send questions/comments to the editors.