When the first Amtrak train rolls into Freeport and Brunswick on Nov. 1, it will be packed with state and federal politicians and the top brass from Amtrak and the Federal Railroad Administration.

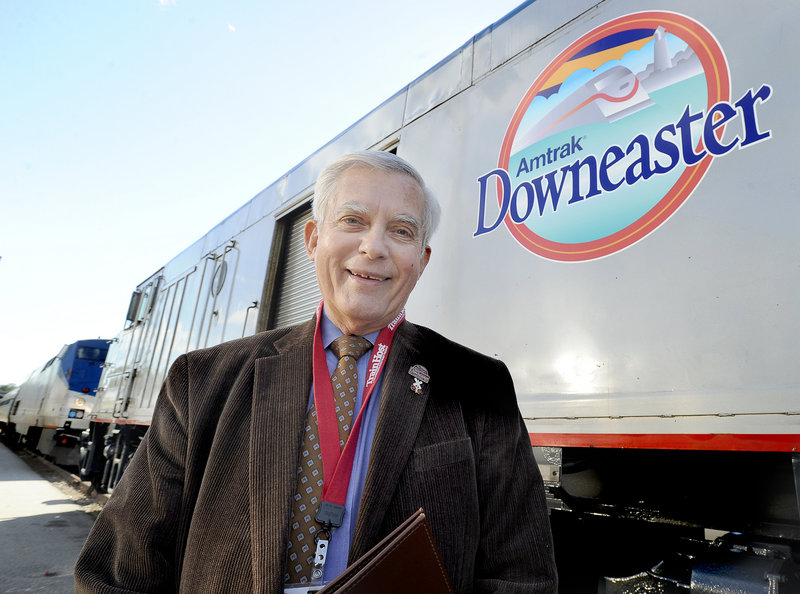

Also on board will be the man who helped make it happen: Wayne Davis, a dapper, 77-year-old retired banker from Topsham.

More than two decades ago, Davis led the grass-roots campaign to revive passenger rail service in Maine. He remains its greatest political asset today.

Davis has the skills and connections of a high-powered lobbyist, although he earns no salary.

His power stems from the same rights enjoyed by all Maine citizens — to organize people, gather signatures for referendums, speak up at public hearings and persuade or prod officials in Maine and Washington, D.C.

His legacy is the Downeaster, one of the most successful routes in Amtrak’s national system. The service between Boston and Portland was established in 2001, and its extension to Brunswick next month will fulfill an ambitious plan that Davis and his supporters mapped out from the start.

“He was very well prepared, well informed, and he had a vision,” said George Mitchell, a former U.S. senator from Maine, who worked with Davis to secure federal funding for the project. “It’s fair to say that the Downeaster would never have happened without Wayne Davis.”

Davis’s involvement in rail issues began in the mid-1980s, when he was head of the Maine chapter of the Mortgage Bankers Association of America and often flew to Washington for board meetings. A blown tire during a landing in Washington scared him so much that he refused to fly again. So he began riding trains to Washington.

On a trip to Washington in 1988, he was so disgusted with the dirty conditions in a sleeping car that he fired off an angry letter to the man listed on the timetable, William Graham Claytor Jr., president of Amtrak.

At the end of the letter, Davis wrote, “P.S., What do I have to do to extend the service to Portland, Maine, so I don’t have to drive to Boston?”

Claytor wrote him a letter of apology and suggested that Davis conduct a public opinion survey in Maine to find out how much support there would be for train service.

Davis obliged. He recruited other train supporters, and in 1989 created a nonprofit advocacy group, TrainRiders/North-east, which today has 900 dues-paying members.

Davis and four other board members borrowed $10,000 and set out to gather signatures for a petition asking the Legislature to pass a law directing the Department of Transportation to bring passenger rail service to Maine. They gathered nearly 90,000 signatures, mostly at the Maine Mall and the Bangor Mall.

Rather than send the measure to voters, the Legislature enacted it in 1991. It was the first time that a citizen-initiated bill became law in Maine without first going to the ballot.

That year, Davis went to Augusta every day for the last three months of the legislative session to lobby lawmakers. At the time, there were many skeptics, said Dana Connors, who was the state’s transportation commissioner.

“He was very persistent. He would never let go, never give up,” Connors said.

Davis succeeded because he was a coalition builder who saw train service as an economic development tool that would work in conjunction with other modes of transportation, rather than taking a nostalgic view of a rail line’s glory days, said Maria Fuentes, executive director of the Maine Better Transportation Association.

In 1995, when the state created a passenger rail authority to manage the service, officials predicted that trains would begin running the next year. But the startup date was delayed repeatedly because of disputes between the rail authority and the company that owned the 78 miles of track between Portland and Plaistow, N.H., over train speeds and track standards.

The service was delayed so often that many people thought it would never start.

It finally began on Dec. 15, 2001, after about $70 million of largely federal spending to upgrade the rails and build stations.

Ridership has nearly doubled since then, from 292,000 in 2002 to a projected 535,000 this year.

Ticket and food sales fund more than half of the Downeaster’s $15 million annual operating budget. State and federal dollars pay the rest. The state subsidy, about $1.5 million a year, is protected from budget battles in Augusta because it comes from a portion of the tax on rental cars.

The 30-mile extension to Brunswick was supposed to be completed by 2004 but Congress never appropriated the money until the recession, when the project was awarded $38 million in stimulus funds.

Over the years, Davis pressed state officials to keep the train service high on their agenda, said John Melrose, who was transportation commissioner under Gov. Angus King. Without that pressure, he said, it would have been harder for officials to stay focused on a project that took so many years to implement.

Davis’s success shows that Maine is the kind of state where one citizen can make a “tremendous difference in the way we live,” said Bruce Sleeper, treasurer of TrainRiders/Northeast. “Without him, we would not have the train. With the train, we have more than a half-million people traveling in and out of the state every year.”

Davis’s focus today extends to the daily operation of the train service. If windows are dirty, light bulbs need replacing or passengers are treated rudely by employees, he will make phone calls.

Davis also calls newspaper reporters and complains if, for instance, they fail to mention the Downeaster’s on-time performance in a story about a snowstorm’s impact on travelers.

Davis is relentless, said Jonathan Carter, who was chairman of the Northern New England Passenger Rail Authority from 1995 to 2002.

If Davis called the rail authority with a concern and didn’t like the answers he got, the authority would soon get a call from one of Davis’s connections, Carter said.

He said Davis’s intensity is softened by a gentle demeanor and an ability to cultivate strong relationships with people in all levels of government.

Davis spends much of his time overseeing a TrainRiders program in which volunteers ride the train as goodwill ambassadors. They give directions, pass out maps and brochures, and sell tickets to Boston’s subway system. They encourage people to get off the train quickly at their stops to limit the time it spends at stations.

The volunteers have helped the Downeaster establish its own identity within the Amtrak system, said Patricia Quinn, executive director of the Northern New England Passenger Rail Authority. Since the beginning, the Downeaster has been ranked first or second in annual passenger surveys.

“Wayne understands that if at the end of the day the passengers aren’t happy, they don’t ride, and then it doesn’t matter what else you build,” Quinn said.

Age has caught up with many of the original board members of TrainRiders/Northeast, and there is concern about how the group will maintain its influence without Davis at the helm, Sleeper said.

Davis himself is showing no signs of slowing down.

Now that service to Brunswick is secured, he said, the focus will be on getting the train to the Lewiston-Auburn area, Augusta and Bangor.

TrainRiders is even pushing for a direct route to New York City. Rather than go through Boston, it could go through Worcester. Davis said he’s already having “exploratory” discussions with Amtrak and Massachusetts officials.

“I think there would be a full train every day,” he said. “If nothing else, we have learned a lot in the past 24 years, and whatever we do now will be much smoother than before because of all our struggles.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.