The timing could not have been better.

It was moments before midnight when the door swung open to the black stretch-limousine parked on Congress Street, and Lisa Gorney and Donna Galluzzo stepped out onto a red carpet unfurled just for them.

Before them stood hundreds of supporters — gay, straight, young, old — in front of Portland City Hall, waiting to count down to the moment that gay marriage would become legal in Maine.

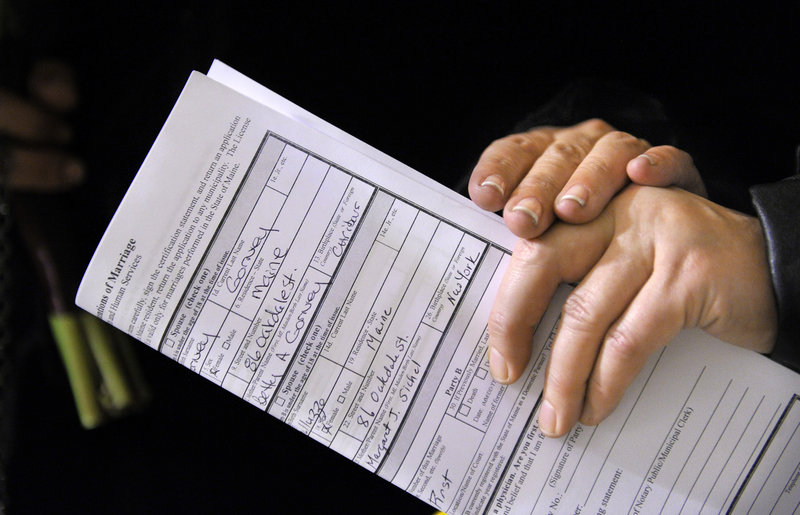

As Galluzzo and Gorney reached the top of the granite stairs on their way to the City Clerk’s office to fill out their application for marriage, the crowd below them erupted. Cameras flashed, and for an instant, all eyes seemed to be upon them.

“I’m shaking,” Gorney said, grinning at her partner of three years.

Less than two hours later on the same stretch of granite where the cries from hundreds of strangers made them feel like momentary celebrities, the two clasped hands and exchanged vows, one of the half-dozen same-sex couples in Portland to wed in the wee-morning hours after the law took effect.

“I truly believe somehow that our love is older than our lifetime here on Earth,” Galluzzo said, before they exchanged rings and kissed for the first time as a married couple.

As it does for many gay couples and marriage equality supporters, the high-flying rhetoric of the national battle over marriage instantly melts in the presence of the people whose lives the law touches the most. Time after time, same-sex couples were greeted by cheers of joy at City Hall in a show of support for everyone’s right to love whom they chose.

For couples like Galluzzo and Gorney, whose lifetimes span perhaps the most dramatic period in gay rights history, the moment is a relief and an affirmation they may not have believed was possible.

“It really was a historic night,” said Galluzzo. “I feel really blessed and really loved and really supported.”

Although neither Gorney nor Galluzzo consider themselves intensely political, both watched this year’s equality campaign with trepidation. When the first attempt at passing gay marriage failed three years ago, the couple had a front row seat to the disappointment, at an after-gathering at the Holiday Inn on Spring Street.

But this time around, Gorney was in bed early on election night. As results of other political contests rolled in, word on Question 1, the marriage equality measure, was delayed.

When the news broke, Galluzzo bounded up the stairs and into the bedroom where Gorney lay sleeping.

“I just said, ‘Honey, it passed!’ ” said Galluzzo, recalling her elation. “It’s hard to describe how happy you feel in a moment like that.”

Across the city at the same Holiday Inn where the couple witnessed the defeat in 2009, a crush of advocates, volunteers and news crews thronged the campaign staff of Mainers United for Marriage.

“I think it’s a huge message that it passed here,” said David A. Hamilton, a notary and friend of the couple who officiated at the ceremony. Hamilton, like other Mainers who anticipated the law in 2009, became a notary so he could cater to gay weddings.

Instead, he spent three years marrying straight people and hoping the electorate in Maine would help nudge the nation toward broader acceptance.

“You grow up as a little kid dreaming of being married, and I did too, but it wasn’t realistic,” said Hamilton. “It’s amazing that we finally live in a world where we can have the same life dream as straight people.”

The wedding caps an intense, three-year courtship for Galluzzo and Gorney.

The couple met in 2000 when they both briefly worked as waitstaff at Katahdin, a restaurant at the time located on Spring Street.

They remained acquaintances, but were in and out of other relationships for years, until Valentine’s Day in 2009, when Galluzzo and Gorney were invited to see a movie with mutual friends. The chemistry was instant.

They exchanged emails and text messages for a week, and even agreed that when they saw each other next, their date should start with a kiss. Gorney said she could feel that it would be her last date as a single woman.

A week later, both said they knew they would be married.

In April of this year, Galluzzo made it official. She proposed in the same booth at the same restaurant where they shared the date. To Gorney’s surprise, in a private dining area below them, a slew of their friends gathered for a surprise engagement party.

“I just knew it, she just knew it.” Gorney said of the engagement. “Even now, every day, I just want to be with her.”

That Gorney, 45, and Galluzzo, 49, would end up on the steps of Portland City Hall hand in hand before a crowd of gay-marriage supporters is a far cry from their early lives. For years, they both dated men, and Galluzzo was even engaged to a man for a time.

Both had scant exposure to gay and lesbian lifestyles while growing up, and both realized their attraction to the same sex much later than many people do today.

Galluzzo, who grew up in Ossining, N.Y., a community that hugs the eastern bank of the Hudson River an hour north of Manhattan, said she had substantial and healthy relationships with men well into her 20s, a fact that made her coming out all the more painful for her family.

Her earliest awareness of gay life came from an uncle, John Sichel, for whom the couple held a moment of silence during their ceremony.

In the spring of 1970, Sichel was missing for eight days. Police were soon involved, and in the course of the investigation the family discovered that her uncle was gay.

A few weeks later, police found Sichel murdered, his body dumped in a sewer, apparently killed by three men in a jealous rage. The intersection of Sichel’s sexuality and his violent death still weighs on Galluzzo, who wonders how her life would have unfolded had she had an ally in the family.

Janet Galluzzo, Donna Galluzzo’s mother, said that Sichel’s murder was connected to his sexual orientation. She said three men went to prison for the crime.

“(Police) felt it was a rage of jealousy,” Janet Galluzzo, 74, said from her Fort Lauderdale, Fla., home, where she lives with her husband, Ed, 78. “It’s something that profoundly affected both my children’s lives.”

For Donna Galluzzo, the connection she feels to the uncle she didn’t have a chance to know better remains deep and spiritual, as if Sichel was a benevolent guiding force.

“I always believed in my heart that he was kind of looking out for me, and that he somehow played a part in bringing (Lisa and me) together,” Galluzzo said. “I do often wonder, had my uncle stayed alive, would it have changed my path? Would I have come out sooner? But you just don’t know.”

Janet Galluzzo said that after she learned of her daughter’s orientation, she was shocked, especially after the longterm relationships Galluzzo had with men.

“I said, ‘I don’t understand. Now all of a sudden you’re gay?”‘ Janet Galuzzo recalled. But the overwhelming desire was for her daughter’s happiness.

“(Donna) had a couple of partners we weren’t nuts about,” Janet Galluzzo said. “The whole family is crazy about Lisa. We all want Donna to be happy and not to be alone.”

Gorney grew up in Caribou, where as a child and teenager she was bereft of any gay and lesbian presence. When anyone mentioned homosexuality, people sometimes jeered, she said.

“No one talked about it,” Gorney recalled. In town, one woman, a teacher, was known to be gay, and she was the subject of ridicule.

“People would drive by her house and be like, ‘Oh my God, there is one gay person in our town.”‘

Gorney’s world opened up when she attended the University of Maine in Presque Isle. She made friends who were gay, and realized there were other ways to live happily and be loved.

But it was knowledge she felt she could not share with her family.

For eight years Gorney kept her sexual orientation a secret. She feared that her father, Art Gorney, chief of police in Caribou for 15 years, would not be receptive.

When she ended the deception in 1991, she first told her mother, Betty Gorney. Her initial response was anger at her daughter’s reluctance to be honest with her family. It also meant there would be no wedding, no grandchildren, no picture-perfect nuclear family.

It took two months before her mother fully digested the news. Gorney said she never directly told her father, but that he slowly acknowledged her lifestyle in little ways.

Betty Gorney, who died in 1997 at 50, gave her husband words of advice.

“Before she died, (my mother) told my father, ‘you have to love your daughter no matter what,’ ” Lisa Gorney said.

It is an edict Art Gorney has stuck to. He said he is happy his daughter found someone who cares for her so deeply, and said Galluzzo is a “tremendous” force in Gorney’s life.

“The world’s changing,” said Art Gorney, 66, from his home in Henderson, Nev. He can’t deny that he still feels a longing for grandchildren, but said his daughter’s happiness is more important to him.

“I support her in whatever she does,” Art Gorney said. “She’s found somebody who loves her. Who are we to say that’s not right?”

Staff Writer Matt Byrne can be contacted at 791-6303 or at:

mbyrne@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.