EXETER — Calling it a win-win situation is an understatement.

Every day in rural Penobscot County, a large dairy farm harnesses clean-burning gas from cow manure and food waste, and it generates enough electricity to power 800 homes continuously. The process, commonly known as cow power, has the potential to earn the facility $800,000 a year. It also creates byproducts — animal bedding and a less-odorous fertilizer — that save the farm about $100,000 a year.

Cow power is more consistent than solar and wind energy, and it eliminates greenhouses gases that otherwise would enter the atmosphere.

The $5.5 million project could pay for itself in five years. After that, it’s all gravy.

So why aren’t more farms doing it?

How to get ‘green’ from brown

For five generations, the Fogler family has milked cows on a pastoral setting of open fields, mixed hardwoods and red barns.

Now the scene includes a distinctly modern facility.

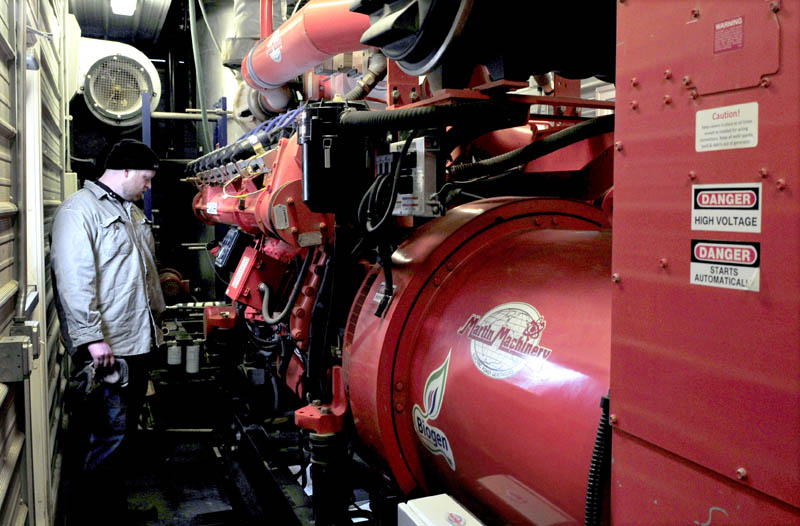

About a mile from the nearest stretch of pavement are two large domes, two towers that occasionally spew flames, a trailer-sized power generator and more. The site’s unconventional appearance sometimes causes passing motorists to pause in the middle of the dirt road to ask John Wintle what it is.

Wintle, the plant and engineering manager for Exeter Agri-Energy, said there’s no quick answer.

“Each question leads to more questions,” he said.

For the past 13 months, Exeter Agri-Energy has been combining cow manure and industrial food waste at this location. In its first year, the company generated 5,200 megawatt-hours for the grid, which earned the farm about $520,000 from Bangor Hydro Electric. Now that the kinks have been worked out, the facility is on track to produce about 8,000 megawatt-hours a year. At 10 cents per kilowatt hour, that’s $800,000.

The project was installed in four months beginning in August 2011. It cost $5.5 million and received $2.8 million in grants from Efficiency Maine, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Treasury Department. The facility is a subsidiary of the Foglers’ Stonyvale Farm, which hosts the project on its land.

Stonyvale also supplies the system with 20,000 gallons of raw cow manure every day.

The manure, which is produced by 1,800 cows, is plowed from the barn floors by a skid steer and diverted into a pumphouse. From there, the manure is pumped about 1,000 feet through underground pipes to Exeter Agri-Energy, where it enters the facility’s anaerobic digesters — two silolike containers that each hold about 400,000 gallons of manure and food waste.

The food waste arrives nearly every day in an 8,000-gallon tanker truck. The waste comes from grease traps and food processors throughout New England and is delivered by a subcontractor. From the trucks, the waste is pumped into holding tanks, where it flows into the digesters and mixes with the manure.

The digesters are heated to 104 degrees, which creates optimal conditions for the bacteria that are naturally present in cow manure. As the bacteria feed and multiply, the mixture exudes biogas — about 60 percent methane and 40 percent carbon dioxide.

As the gas pressure builds, the containers’ rubber tops expand like balloons and give the containers a domelike appearance. When pressure is sufficient, gas travels through pipes to a 1-megawatt generator.

The generator runs almost constantly throughout the year, except during maintenance periods. The exhaust leaves the generator through a short stainless steel stack, about the size of an exhaust pipe on a farm tractor.

Travis Fogler, operations manager for Stonyvale Farm, said the gas burns cleanly.

“When you look at the rain cap on the exhaust, it’s just clean,” he said. “If that was a diesel engine, the cap would be black from all the carbon. It’s just not there.”

As the mixture breaks down in the digesters and the pressure subsides, the system’s computer automatically pumps more raw manure and food waste into the containers to keep the bacterial process rolling.

At the same time, spent material is pumped out of the containers, where it passes through a mechanical liquid separator. Plant fibers that aren’t broken down during the anaerobic digestion process are separated from the water and reused. All day long, the fibers churn out of the machine in bone-dry clumps that fall into large piles that are used for cow bedding or compost.

The liquid from the separator is pumped back to the farm, where it spills into lagoons that once held raw manure. The liquid contains all the same fertilizing nutrients found in raw manure, but it’s better. The liquid is easier to spread on fields than manure; plants absorb its nutrients more easily; and it is virtually odorless, said Wintle, 37.

Those two byproducts save the farm about $100,000 a year, Fogler said. The greatest savings are found in fertilizer costs. It’s not that they produce more fertilizer; they can just use more of what they have.

“Manure before digestion stinks, so all summer long we would purchase (commercial) fertilizers because we didn’t want to aggravate our neighbors with the odor,” said Fogler, 35. “The digestion process removes the odor, so we’re able to spread it all summer.”

Donna Wagner has lived about a half mile from Stonyvale Farm for the past seven years. She said the odor reduction was immediately noticeable.

“It is less smelly, even during the summer,” she said.

Town Manager Tressa Smith said the project is viewed favorably within the rural community of 1,062.

“Everyone from the town has supported it, and it has been great. I’ve heard no negative feedback whatsoever,” she said.

Smith is also a neighbor of Stonyvale.

“I’m happy with it,” she said of the project. “I don’t smell the cow manure anymore. I can hang my clothes outside.”

Why isn’t manure power spreading?

In the United States there are about 100 cow-power facilities. Only a dozen combine food waste with manure. In Maine, there is only one.

Curt Gooch, dairy sustainability engineer at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., said digesters first appeared in the U.S. in the 1970s, during the oil embargo; however, when oil prices dropped again, interest in the technology dried up. Then, in the late 1990s, there was a resurgence. Digesters have continued to crop up since then, but it’s still not widespread

“The potential is huge,” he said. “It’s a big bud that’s waiting to blossom.”

In Europe, cow power is in full bloom. About 5,000 anaerobic digesters operate in Germany alone, Gooch said.

There are several reasons why, said Spencer Aitel, co-owner of Two Loons Farm in South China and board member at Maine Organic Farmers and Gardners Association in Unity.

Cow-power producers in Europe are paid three times as much per kilowatt hour; European countries are more densely populated, so odor control is highly valued; and European governments tightly regulate milk prices so they’re always profitable for dairy farmers.

Installing cow power requires a substantial investment, which is extremely difficult for U.S. farmers, who are often in the red. On Friday, for instance, 110-year-old Garelick Farms ended production because the cost of making milk exceeds the amount dairy farmers receive.

Also, the technology is viable only for very large farms, Aitel said.

Prudence Flood is part owner of Maine’s largest dairy farm — Flood Bros., in Clinton. Flood said she has looked into the possibility of cow power and it looks promising; however, a system for her 3,800-cow farm would cost about $10 million. At the moment, the price of milk is too low to justify such a large expense.

Flood added that the Obama administration isn’t pushing for cow power in the same way it has supported wind and solar energy projects.

Gooch agrees.

“You certainly don’t hear the president talking about biogas as renewable energy,” he said. “Biodigesters are never going to replace solar, wind, hydro or anything else, but they are going to add to the portfolio.”

Gooch said it’s difficult for cow-power facilities to match the output of wind and solar, but it is a more consistent form of energy.

“Ninety percent of the time, the engine is running,” he said of cow power. “Solar is only going to be half that because the sun isn’t shining at night. Wind farms are generating electricity about 30 percent of the time.”

Beaver Ridge Wind, in Freedom, for instance, produces about 12,500 megawatt-hours per year with its 4.5 megawatt facility, according to its website. Beaver Ridge’s potential for energy creation is 350 percent greater than Exeter’s 1-megawatt generator, but it produces only 52 percent more electricity.

While it’s beneficial to harness wind energy that otherwise would be wasted, wind isn’t damaging to the environment, unlike methane. Using food waste for energy also lessens the burden on landfills, Gooch said.

A Cornell study found that for every two cows whose manure goes into a digester, it’s the equivalent of taking one car off the road, in terms of greenhouse gases, Gooch said. In the case of Stonyvale Farm, that’s like removing the emissions of almost 1,000 cars.

While wind farms often are criticized by nearby residents, neighbors of cow power facilities are generally pleased, said Adam Wintle, a managing partner at Biogas Energy Partners.

Biogas Energy was a development partner for the Exeter project, and manages its finances. The company also is seeking opportunities to bring new cow-power facilities to Maine.

Wintle, who is John Wintle’s brother, has a background in real estate and commercial development. He said the community perception of biogas is a departure from his past commercial projects.

“There’s always some organization that’s trying to knock you off your feet, but we just didn’t have it with this. Socially, environmentally and economically, there are so many positives.

“Everyone likes it.”

Ben McCanna — 861-9239

bmccanna@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.