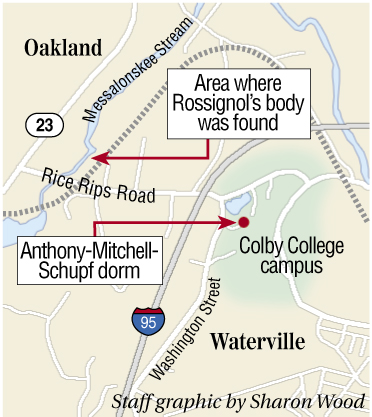

WATERVILLE — On Sept. 16, 2003, Dawn Rossignol, a promising pre-med student, left her Colby College dormitory room a little after 7 a.m.

She didn’t know she was being watched. Edward J. Hackett Jr., a parolee from Utah who was visiting his parents in Vassalboro, was looking for someone to attack. He picked Rossignol.

Her body was found a day later, near a stream off Rice Rips Road in Oakland.

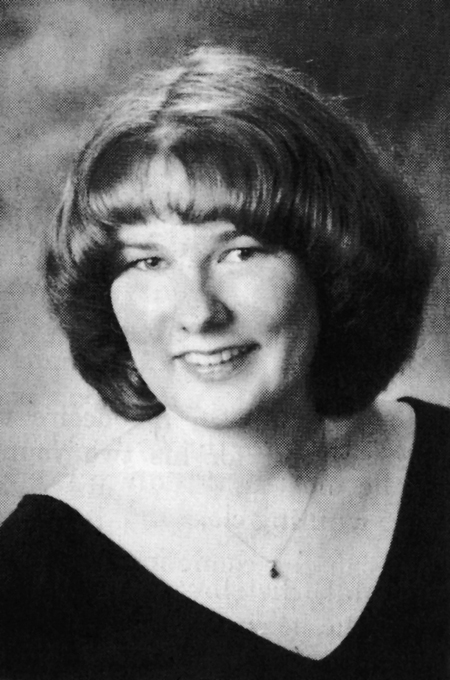

The murder of the 21-year-old senior from Medway, who hoped to be a pharmacist, made national news and shocked the Colby community, which many thought of as a sanctuary from crime and violence.

Rossignol’s death challenged that perception, as well as shed light on the challenges the corrections system and mental health care providers can play in resolving mental health problems.

Thousands of students have passed through the Colby College campus since Rossignol was murdered, but her story is still remembered for many reasons, including the role it played in the development of safety on the campus.

Rossignol’s murder wasn’t a wake-up call, but it gave a face to the message campus police and security send out every year as hundreds of new students come to campus.

Waterville police and Colby security officials at the time agreed that Rossignol’s murder could have happened anywhere and that the college’s security was good.

“Everyone who looked at this situation agreed that it was a random act. Colby is comfortable that our security protocols were more than adequate at the time,” spokeswoman Ruth Jacobs said.

Still, there have been changes to the way the campus responds to emergencies.

Jacobs said the 2007 Virginia Tech shootings, in which 32 people were killed and 17 wounded, were a factor in the college’s efforts to improve emergency communications by setting up a siren system and a system for sending text messages and emails to the campus population.

Maine has the lowest crime rate of any state in the country, with 123.2 violent crimes reported per 100,000 inhabitants in 2011, the most recent data available from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Yet the state’s college campuses must work continually to raise awareness among students, faculty and staff, said Noel March, U.S. marshal for the District of Maine and former head of security of the University of Maine.

“We’ve learned differently,” he said. “From Virginia Tech to Colby College, we know that our college campuses, while safe, are not risk-free communities that live in a bubble of safety.”

‘That killer stalked her’

Hackett watched Rossignol that September morning 10 years ago as she walked into the parking lot and unlocked her car.

“That killer stalked her and had a plan for how he was going to carry out his crime,” March said.

Hackett, 47, was on parole from the Utah prison system, where he’d been convicted for burglary and kidnapping, when he told mental health care providers he knew he was not going to be successful and that he planned to do something violent in order to get back into the structured setting of prison, according to Waterville attorney Pamela Ames, his court-appointed lawyer.

That morning, Hackett planned a kidnapping and sexual assault.

He parked his car in the parking lot and he watched her approach, Ames said. She said he had identified a specific car. If Rossignol got into that one, he would not take her.

She walked past the car he’d picked out and continued to her own.

Hackett already had checked out the site of the water treatment plant where he brought Rossignol in her car, tied her to a tree and sexually assaulted her, Ames said. After the assault, Hackett didn’t know what to do with her, and fearing that she would tell someone, he smashed her head in with a rock. Her cause of death was blunt force trauma to the head.

Police caught Hackett six days later after his name came up when they combed records to see whether anyone in the area had been convicted of a similar crime. After he was arrested — announced at news conference on the Colby campus — police gave out little information about their investigation.

“That week was an extremely tense week on campus,” college Vice President Sally Baker said. “People didn’t know who did it. They didn’t know anything about it except that they felt unsafe.”

Ames said Hackett “certainly knew what he was doing was wrong.”

“But it also shows how mentally ill he was at that time,” she said.

Mental health time bomb

Ames said the 18 months Hackett spent in Maine was the longest he had ever been out of the prison system since he was 16 years old and that he made comments to her about his struggle to make it in society.

He was a patient at three mental health agencies, and the agencies had the authority to report to Maine probation and parole if there were red flags or indications that he was not taking prescribed medicine, was not compliant with therapy, was having violent tendencies or was making threats of violence, Ames said. She would not release the names of the organizations that provided counseling for Hackett, all in the Augusta area, and said they are under different management now.

“They all knew he wasn’t taking his medication,” she said. “They all knew he was abusing substances, and they all knew he was expressing frustration with living at home, not being able to find employment and not being able to move forward with his life. They all knew he said he believed he was going to do something.”

Hackett is 6 foot 3 inches and weighs 240 pounds.

“He was scary and he knew it. He used it to his advantage and would often intimidate service providers,” Ames said. She said Hackett often left counseling sessions angry, making threats or saying he needed to go back to prison because he couldn’t cope, behavior that she believes is rampant in the mental health care system.

Hackett was sentenced to life in prison in March 2004 for Rossignol’s murder, after pleading guilty to charges of murder, kidnapping, aggravated assault and robbery in Kennebec County Superior Court.

In the 10 years since Hackett killed Rossignol, Ames said she hasn’t seen a change in mental health care services, although more are diagnosed as mentally ill today than in 2003.

“We’re just operating a revolving door,” Ames said. “When we have seriously mentally ill individuals who are also within the criminal justice system, they are separated from society, returned to the streets and go right back to that behavior.”

Joe Fitzpatrick, clinical director for the Maine corrections department, said the department does what it can.

“We try to address the needs of all our prisoners, including mental health issues, substance abuse issues and educational deficits while they are incarcerated so that we mitigate the risk to the community when they leave,” he said.

“Oftentimes the population in the correctional system doesn’t have ready access to mental health therapists and specialists in the community. When they’re with us, they have that access.”

He said the department helps prisoners who are being released, setting up appointments and helping with applications for MaineCare, which is not available in prison.

“We spend a lot of time trying to connect them to resources in the community. There are some areas of the state where there aren’t a lot of resources and we do the best we can, but it can be challenging,” he said.

The prison system evaluates prisoners as they enter the system and again when they leave to determine if they are a danger to themselves or other people, said Fitzpatrick. If there are concerns about a prisoner’s violent history, the corrections system can start paperwork to enroll them at Riverview Psychiatric Center, the state’s mental health hospital.

A criminal defense lawyer, Ames estimates that 90 percent of her clients have a mental illness.

She said the problem is that mental health care in prison is optional.

“Most of the mentally ill don’t think they have a problem,” she said. “We may not even know they have a problem unless they are acting out.”

And while there is more recognition of the impact that mental illness can have on crime, that knowledge does not make it easier to provide access to what is needed, she said.

She said it’s also hard to offer the amount of preparation necessary to give some prisoners a successful life outside of the system, where they face stresses such as lack of housing, jobs and money.

She said in the end, society feels better and safer if mentally ill people are not on the street.

“Society would rather have them in prison, so they don’t do things like Mr. Hackett did, and you end up with a completely innocent victim being killed,” she said.

A lasting presence

There was little the Colby campus could have done to prevent Rossignol’s murder.

But officials hope that knowing it can happen will make students more aware of how to stay safe.

Earlier this month Colby welcomed 487 new students. With an ever changing population, there is always the need to educate students, faculty and staff about security, said March.

Spokeswoman Jacobs said campus security has changed over the last 10 years, but not as a direct result of Rossignol’s murder.

Her death was not the first on the Colby College campus — the 1971 murder of 18-year-old Kathleen Murphy, whose body was discovered in a ravine near campus, remains unsolved.

Crime on campus is a reality. According to the college Department of Security, there were 52 crimes reported on campus in 2012, 37 of which were classified as larceny and 13 burglary. Two sexual assaults were also reported. She said Rossignol’s death so early in the school year set the tone for the year — everyone on campus felt unsettled.

Ten years later, the students in Rossignol’s class have graduated and there are few people left on campus who knew her, but her presence is still felt, said Baker, the admissions vice president.

Baker worked in the same building as Rossignol, who worked in the office of alumni relations.

“There are a lot of reminders for those of us that work here,” Baker said. “She had a wonderful reputation with her boss and her professors. She was thought of as a bright, solid student who was going on to pharmacy school. She had already been accepted and was looking forward to that.”

Baker said Rossignol’s death has made her more vigilant, checking to see who’s walking through the doors in campus buildings, for instance.

On Monday, the bell at Lorimer Chapel will ring 10 times for the 10 years that have passed since Rossignol was murdered.

“It’s been 10 years but it still feels like it was yesterday,” said her mother, Charleen Rossignol. She said that when her daughter died there were a couple of events on campus to remember her, for example a road race. She said she hasn’t kept in touch with Colby College since her daughter’s friends graduated. Her roommate is getting a doctorate at Northwestern University.

In the spring of 2004, Colby College presented Rossignol’s family with an honorary bachelor of science degree, something the college rarely gives to someone who has died, Baker said. It was a special moment at the class of 2004 commencement and provided some sense of closure for those on campus, she said.

Baker said Rossignol is missed, but a positve came out of her death.

“We haven’t stopped grieving for Dawn, but I feel like we’ve moved on in the way we feel about our safety,” she said.

U.S. Marshal March said it shouldn’t just be a lesson for those at Colby.

“It became a glaring example of how bad things can happen to good people right in our very own state,” he said. “If it can happen an hour south of us, it can happen here. And if it can happen at 9 a.m. on a drizzly morning in daylight it can happen anywhere.”

Rachel Ohm — 612-2368

rohm@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.