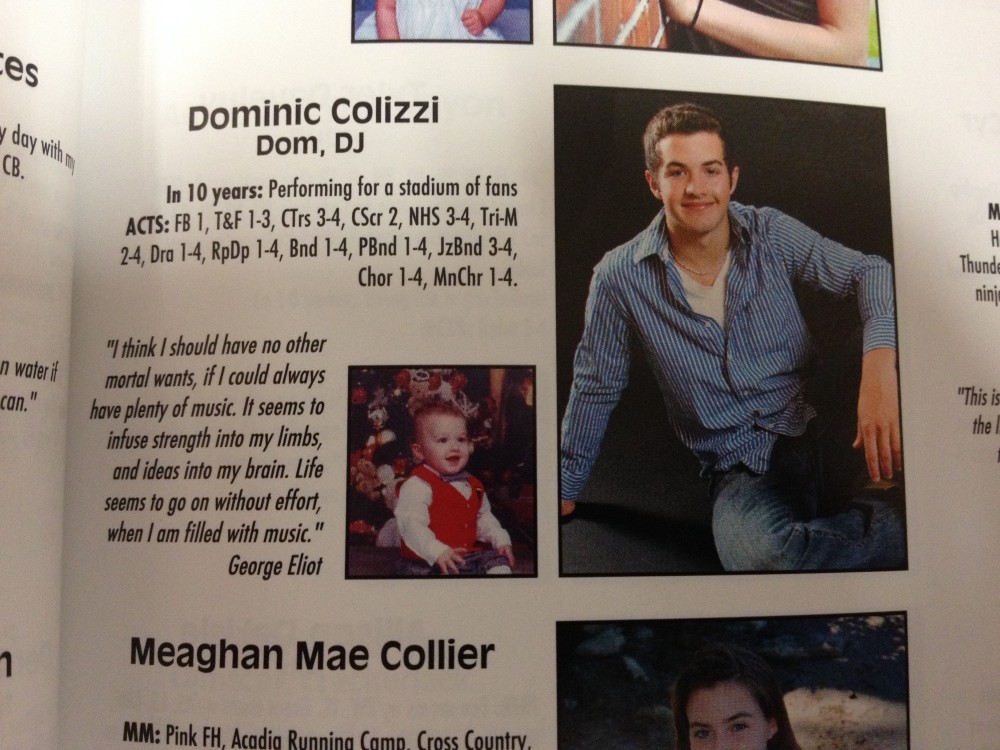

Before Dom Colizzi graduated from Oakland’s Messalonskee High School in 2011, he was an easy target for bullies.

“High school,” he said, “was the worst.”

When he gave up football for music and drama in his freshman year, many of his friends drifted away.

Colizzi’s creative aspirations, urban fashion sense and lisp added up to one thing for some of his peers.

“I was called ‘faggot’ a lot,” he said. “If somebody says it, rumors spread like wildfire.”

Colizzi, 21, formerly of Oakland, is now making his living as a country music performer in Nashville, Tenn. He is returning to his home area to perform at the Waterville Opera House on Wednesday night along with Joel Crouse, a 22-year-old singer who has been touring nationally with country superstars like Taylor Swift and Toby Keith.

The show is important to Colizzi’s career and his psyche. It’s also the official kickoff of Colizzi’s anti-bullying campaign, built around a song he wrote based on his experiences with bullies.

“A lot of people doubted me. I had people say I was an embarrassment to my town,” he said. “Being able to perform with a national star like Joel is a kind of redemption for me. I’m just looking for my hometown’s support.”

Colizzi said he never made the connection between his high school problems and his music career until his manager suggested he write about those experiences.

The end result was “Somebody’s Hero,” a single that speaks directly to young people who might feel isolated by the words of their peers.

“Whenever you need me, shine that light in the sky,” he sings, “I’ve got to be somebody’s hero.”

Colizzi said when he began performing the song for live audiences, he could see that it was really having an impact.

His publicist, John Stuart, is fervent about the power “Somebody’s Hero” has demonstrated with its listeners.

“At least two women cry every time he plays it,” he said.

Colizzi said people began approaching him after his performances to share their own experiences with bullying.

Now, he said, he is actively trying to use the song as a jumping-off point for discussions with young people.

He is booking a series of high school and middle school performances beginning in the fall, so that he can bring his message directly to teens.

“If I could tell them anything, I would tell them keep fighting,” he said. “Fight the good fight. At one point, everything will change and no matter what happens they will pull through. They’re going to be in a spot where they can help another kid.”

Colizzi’s memories are still fresh enough to be painful for him.

“I’ve had haters since I was 13,” he said. “I felt very alone.”

He couldn’t get a date to prom. Even when he sang, the activity that he loved, people would mimic him, exaggerating the lisp.

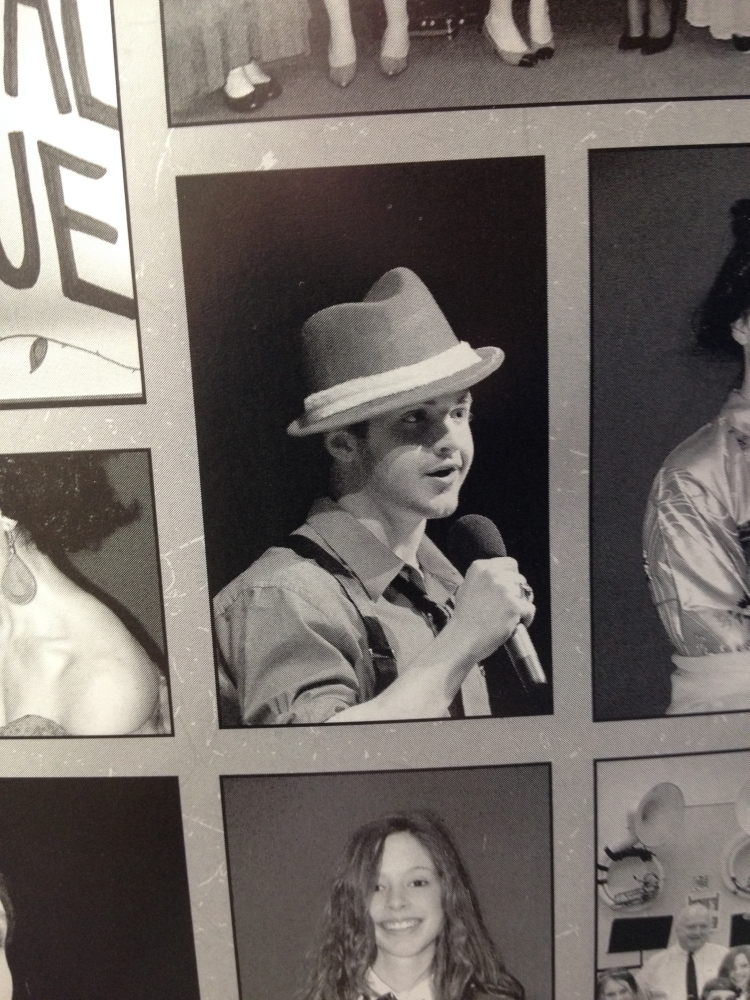

Colizzi said he didn’t try to hide his differences. While other less popular students tended to stay in the shadows, he continued to dress and behave in a way that defied his tormentors.

“I would wear a T-shirt and a vest,” he said. “I would have a hat that most people weren’t wearing. A lot of other people would wear ballcaps. I like to wear those too, but I had a little bit of a preppier style.”

He saw former friends go through degrees of indoctrination. First, they would get less comfortable around him in the presence of others. Then they didn’t want to be around him at all. Eventually they would join in with the insults.

Messalonskee High School librarian Sylvia Jadczak said she was surprised to hear that Colizzi was bearing the brunt of bullying.

“He was always so positive and outgoing,” she said. “He had 10 times as many admirers as detractors.”

But sometimes, all it takes is one bully to leave emotional scars, says one expert.

Susan Greenwood is the executive director of the Cromwell Center, a Portland-based organization that fights against bullying as a component of a broader mission of disabilities awareness.

“What he’s going to remember is those kids who were mean and who did make fun of him,” Greenwood said. “When kids have friends, it makes a huge difference but it’s not going to erase the negative feelings.”

Greenwood said that a performer like Colizzi can be a powerful force for change among young people.

“Being close to their age is certainly a benefit,” she said. “And he’s successful, doing something in the arts, which get a lot of attention.”

Colizzi’s transformation from bullied outcast to country hunk didn’t happen overnight.

He underwent tongue surgery two years ago to correct the lisp.

His parents, David and Roanne Colizzi, and a core group of friends have been stalwart supporters as he released independent singles on iTunes or a homegrown music video shot at the Opera House on YouTube.

Earlier this year, he was still splitting most of his waking hours between working at Aeropostale, a clothing retailer, and the chain restaurant Friendly’s. At nights, if he was lucky, he would have a gig lined up as a DJ.

His career really began to take off a few months ago, when he moved to Nashville, Tenn., to pursue his dreams full time.

Now, things are starting to look up. He’s played about 60 venues over the past couple of months and added thousands of Facebook friends. People are crying at his performances. For the first time in his life, he’s making a living doing what he loves.

Colizzi said that, while some things have changed, other things remain the same.

Some of his peers that once gave him the cold shoulder have become more welcoming when they see him, he said. Others have not.

“They’ll always be the same person, that will continue to hate on somebody no matter what,” he said.

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling — 861-9287

Twitter: @hh_matt

Send questions/comments to the editors.