By the time Peter Francis’ assailants walked free, Don Gellers had made plenty of enemies.

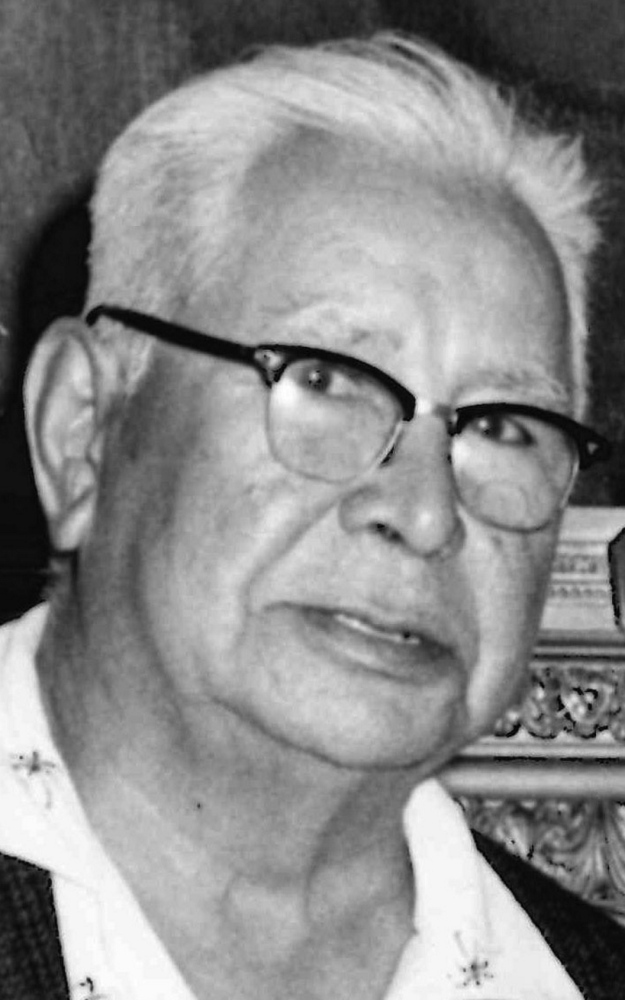

After his first meeting with tribal Gov. George Francis in May 1964, the young attorney had thrown himself into representing the Passamaquoddy in matters great and small.

Within hours, he’d managed to get the charges dropped against the four Passamaquoddy women who’d been arrested in the “gravel pile” protest against a white man’s seizure of reservation land, and negotiated a truce whereby construction stopped on the contested parcel pending legal rulings. He then forced the presiding judge in the case to recuse himself, after showing he had signed the papers allowing the white camp owner to annex the Indians’ land.

Gellers’ letters to state officials compelled the Legislature to pay for emergency repairs to leaking sewerage systems on the reservation, and a rewriting of laws that had prohibited tribal members from hunting on their own reservation land. Barbers in the town of Princeton were required to accept Indians as patrons.

He had blocked an effort by the Town of Perry to evict the Altvater family from their home. When administrators at Shead High School retaliated by telling two of the Altvater children they would no longer receive free school lunches, Gellers protested to state officials, who forced the school to reverse itself.

When state police arrested two Indians for minor offenses on reservation land, Gellers successfully challenged the state’s jurisdiction in a case that was at one point reviewed by Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black. The final decision by the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals – the second-highest court in the land – transferred authority over certain misdemeanors by tribal members on reservations from Maine to the tribes themselves.

Gellers and the governors of the two reservations also launched an investigation of state Indian agent Hiram Hall and found evidence that he had made himself the legal guardian of numerous Indians and likely pocketed public pensions and benefits they were owed. “They served the summons on Hiram that day telling him he had to come to court the following week,” recalls John Stevens, who was then governor at Indian Township. “He died that night.”

Gellers and the chiefs successfully lobbied the state to shift oversight of the Indians to a separate Indian Affairs Department, which opened just months before Peter Francis was killed in November 1965. The top officials were replaced by a bearded 32-year-old anthropologist, Ed Hinckley, who wished to increase Indian self-government.

Gellers hosted press visits and organized events to draw attention to the Passamaquoddy’s plight. At an NAACP meeting in Portland in the aftermath of the brutal attacks on black civil rights marchers in Selma, Alabama, Gellers, along with an Indian elder and a local minister, emphasized the parallels between the racial prejudice Indians faced in Washington County and that suffered by blacks in the American South.

Most significantly, Gellers was conducting research for the tribe’s land claims case against the state, which Maine Gov. John Reed and the Attorney General’s Office had already refused to support.

Gellers worked on contingency, meaning he would get nothing unless he was successful. Even so, researching the case was an expensive undertaking. In the first few months, Gellers had traveled to archives in Boston, New York, Washington, D.C., and Fredericton, New Brunswick, to gather documents that would prove the Indians’ case. In that time he’d spent $1,000 out of pocket and expected to need an additional $5,000 over the next two years. This presented a problem, as the Indians had no money in hand and Gellers was quickly running out of his own.

The obvious solution was the Indians’ trust fund, which contained $60,000 in proceeds from state-supervised paper company logging on their reservation, but it was completely controlled by the governor of Maine and his executive council. When Gellers and the tribe approached Reed for an initial disbursement of $3,000 to cover research expenses, the governor flatly refused.

“It is the unanimous opinion of the council and the opinion of the governor as well, that there is not sufficient possibility of benefit for the Indians,” the chairman of the executive council wrote George Francis the month before his brother Peter’s killing, “… for it to be wise and prudent action to commit trust fund money for the purposes outlined by Mr. Gellers.”

Gellers rebuffed a counteroffer to give him three $1,000 payments – one before, one “halfway,” and one at the completion of his case – and nothing more. He told reporters it was a “cheapening and degrading offer,” “cracker-barrel bargaining” and “a nifty way to get a final bargain from people who have been pushed around so much already.”

The Indian chiefs were just as blunt. Pleasant Point Gov. George Francis said the trust fund was “our money and we demand it,” while Gov. Stevens told Reed “you should be giving us a helping hand rather than putting handcuffs on us.”

Cut off from their only assets, the tribal governors and their attorney also faced increasingly disturbing attacks.

Gellers soon found his legal services were no longer in demand among the white residents of Eastport. “His business went right downhill after he started representing us,” Stevens recalls.

Signs appeared on the lawn in front of Gellers’ Eastport home, denouncing him as a communist and worse. At one point swastikas were painted on his walls – Gellers was Jewish – an act he said was committed by a local public official, whom he later confronted over the incident. Another Eastport town father opened his hand to show Gellers’ clerk two bullets, saying one was for Gellers, the other for George Francis.

Police began harassing Gellers and the tribal governors, subjecting them to regular traffic stops. “I wouldn’t go anywhere without being stopped, and I imagine they was watching all of us,” Stevens says, noting he would be stopped twice on his 14-mile commute to work in Baileyville. “Christ, when Don would come pick us up, they’d stop him in Calais, they’d stop him in Woodland. They’d take him back to the courthouse trying to find out what he was up to. Wouldn’t charge him, they’d just let him go. But it took him three hours to get up here.”

State officials cut off food and medicine to members of Francis’ and Stevens’ families, who would find windows broken at their homes and car tires slashed.

Frightened, many Indians signed petitions calling for George Francis to be removed as governor and submitted them to state officials, led by Francis’ political rival, Joseph Nicholas, an apologist for the state whom some Indians dismissed to reporters as an “Uncle Tomahawk.” Nicholas, then the tribe’s non-voting representative to the state Legislature, tried to have Gellers removed also. Washington County officials apparently approved: A few months later he became the first Indian ever allowed to serve on a jury there.

“I was like Joe Nicholas at first – thought it was a waste of time fighting the state for food and stuff, that we’d never get anywhere, and we’d hurt people since they had control of all the resources coming into the reservation,” Stevens says. “I came around, but I should have been fighting alongside (George) all along.”

Just before his brother’s murder, George Francis lost his re-election bid, dealing a temporary setback to the Passamaquoddy’s burgeoning civil rights movement.

Gellers and his wife were living hand to mouth. His office assistant, Frances Tomah, discovered one day that most of the food containers in their pantry were completely empty, retained to hide their worsening situation. Unable to afford oil, they heated the rambling, 32-room home at Middle and Water streets entirely and only half-successfully with wood.

Susan Gellers, unable to take the strain, left her husband.

Gellers continued smoking marijuana but was taking fewer pains to conceal this illegal habit, seemingly oblivious to the forces seeking to take him down.

Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Coming tomorrow:

Land claims case solidifies

Send questions/comments to the editors.