As a result of an unusual 1986 tribal caucus initiative, hundreds of Passamaquoddy had their right to vote in tribal elections taken away because they lived outside Washington County.

A Passamaquoddy living in Steuben – an hour-and-40-minute drive from Pleasant Point – could vote for office there, whereas if he or she lived in equidistant Aurora, he could not, simply because it was over the Washington County line.

It appeared to represent a clear violation of the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution and the Indian Civil Rights Act. Had the Passamaquoddy remained under federal jurisdiction or unfettered state jurisdiction or if the tribe had passed a constitution of its own, the disenfranchised Indians would have had no trouble having their case heard.

But as a result of the 1980 land claims settlement, judicial review of “internal tribal matters” such as this apparently fell into nobody’s jurisdiction at all.

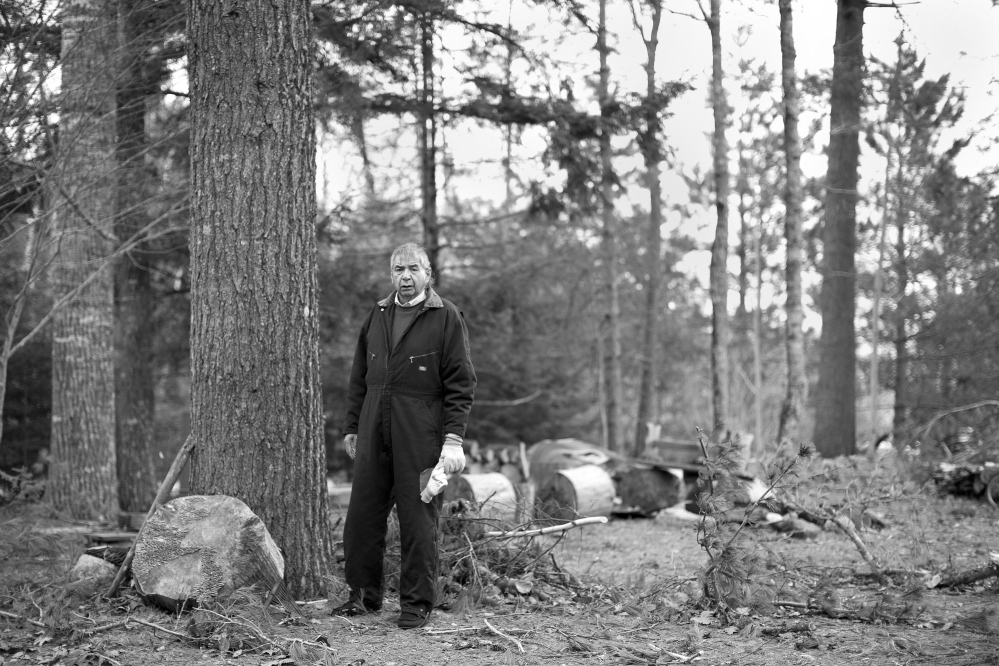

Former Indian Township Gov. Allen Sockabasin and another nonresident tribal member, Gail Dana, tried to challenge their disenfranchisement in the tribal court, a body set up precisely to hear cases involving internal tribal issues. Or so they thought.

They filed their complaint, alleging violations of the equal protection clause of the federal Indian Civil Rights Act and traditional tribal practice, and seeking a restraining order to prevent the Sept. 2, 1986, election from going forward.

According to Sockabasin, the tribal court proceedings were a farce. In the midst of the court hearing, he recalls Tribal Judge John Romei calling a recess. As the court had their break, Tom Tureen, the attorney who had represented the Passamaquoddy and Penobscots in the land claims settlement, convened a joint tribal council meeting in the next room. There, Sockabasin says, Tureen advised the council to pass an ordinance forbidding the court from ruling on electoral matters.

“Tureen came back in and advised the judge on what had been done,” Sockabasin recalls. “Right in the middle of the court proceedings they changed the law.” (Tureen says he has no recollection of these events; Judge Romei did not respond to an interview request.)

At the end of the proceedings, Romei ruled the tribal courts did not have jurisdiction, as the tribal council had not given them such power.

T

he plaintiffs appealed the decision to the Penobscots’ tribal court, which serves as the appeals court for the Passamaquoddy (and vice versa). Appellate judge Andrew M. Mead – who is now a justice on the Maine Supreme Judicial Court – issued a sobering decision on June 3, 1987.

“The Passamaquoddy Tribal Court is not a constitutional court. It has no existence separate and apart from the government of the Passamaquoddy tribe,” he wrote. “Accordingly, the court … can exercise no powers beyond those authorized by the tribe. Indeed, the tribe could extinguish the court at any time by appropriate legislation.”

Mead said he was “aware of no legislation, resolution or council action which would authorize it to entertain an action against the tribe itself. … As such, a tribal member may not seek redress for tribal (government) action before the Tribal Court.”

Translation: absent a constitution making it a separate branch of government, the tribal court did not have the power to judge the actions of the tribal government and, in fact, served at its mercy. (Mead did not respond to an interview request.)

An “internal tribal matter,” Sockabasin and Dana had just discovered, is one not subject to judicial review.

Would the federal courts have heard his case? Would they have determined whether the Indian Civil Rights Act applies to Maine tribes? Allen Sockabasin was ultimately unable to find out.

Lacking the funds to pursue the case in federal court – and unsure if it would even be heard – Sockabasin was forced to abandon his efforts.

Any Passamaquoddy who lives outside of Washington County still cannot vote in tribal elections today.

One clear political effect of the ban, many in the tribe say, is that the portion of the tribal electorate least likely to be beholden to government officials for their livelihoods had just lost their say in who those officials would be.

“They hand people money and expect their support or give them contract jobs for their support, and that’s how they keep control of people in the community,” says tribal member Ira Gilbert of Indian Township.

Regardless of the virtues of disenfranchisement, the incident foreshadowed what would become the tribe’s greatest liability, the Achilles’ heel that has hobbled its ability to build a prosperous future for its people: the lack of a constitution that would establish the fundamental laws of the tribe and the foundations of the rule of law in internal tribal matters.

Traditional tribal structures, Sockabasin told the Maine Times in the fall of 1986, were inadequate to cope with the administration of tens of millions of dollars of grants, corporate assets, and trust fund investments secured as a result of federal recognition and the land claims settlement.

But efforts to approve a constitution to rectify the matter had failed, Sockabasin told the Maine Times, “because the constitution would have made the entire leadership accountable. From what I gather, nobody wants to be accountable. But we’re just dealing with too much money not to be held accountable.”

His words would prove prophetic.

Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Coming tomorrow:

A constitutional crisis in the making

Send questions/comments to the editors.