Each time Nancy Rosalie, of Thorndike, makes a death shroud in her home, she spends hours hunched over her 100-year-old Singer sewing machine, working the foot treadle as she carefully stitches together the last garment her client ever will wear.

Rosalie says she started offering the service to provide a different option for burial.

“It’s very interesting, having a business in which the product depends on people dying,” she said.

Rosalie is part of the Funeral Consumers Alliance of Maine, which promotes a different kind of funeral aesthetic. Members of the group say funerals can be simple, dignified and economical, and still be meaningful.

The group is representative of those who have rejected the idea that a funeral business has to handle the intimate details of saying goodbye to a loved one.

Because there is no need for embalming fluid, metal caskets and concrete vaults, the group’s agenda is at odds with some of the most important revenue streams of traditional funeral homes.

Rosalie said that over the past 100-plus years, the funeral industry has driven a wedge between America’s living and their departed loved ones.

When it became the norm for funeral directors to prepare and transport bodies behind closed doors, it became easier for people to avoid the issue of death, she said.

“Americans are very good at ignoring the fact that death happens to all of us,” she said.

MAKING A SHROUD

A body can be an unwieldly package, especially after rigor mortis passes. It must be washed, dressed and transported to its final resting place, all of which is made more difficult when the arms and legs go limp, Rosalie said.

She has made only a handful of shrouds so far; and each one, she said, is designed to be both meaningful and practical.

The bottom of each shroud consists of a cloth platform, a sturdy piece of fabric that serves as a base for the body. The platform typically is filled with batting that can absorb fluids if necessary, and it is easily carried with three sets of handles on the ends of straps running beneath.

On top of the platform is another piece of cloth, used to wrap the body and keep the limbs close to the torso.

Rosalie uses only re-purposed fabric — silk, wool, cotton curtains, upholstery and linen tablecloths. Flannel sheets are a favorite of hers. “They just seem so cuddly,” she said.

Finally, a strong lace, such as a shoelace, is used to secure the wrapped body to the platform, to prevent the body, or an errant arm or leg, from spilling off the edge of the platform during transportation.

A shroud can be placed inside a casket or it can be placed directly into the ground, she said.

“It’s this nice bundle with the carrying handles,” she said. “It makes it very easy to transport the body to wherever you’re going with it.”

That shrouds are a legal alternative to a metal casket might be a surprise to many consumers.

Under state law, Maine residents can be buried in a wide range of containers — a handmade wooden coffin, a biodegradable cardboard box, a shroud in a casket, a shroud by itself or even nothing at all.

Many mainstream cemeteries won’t accept a body in a simple shroud or a coffin unless it is encased in a cement vault. The vaults are needed to prevent the ground from sinking during decomposition, said Steve Burrill, an officer with the Maine Cemetery Association, who said so-called “green” burials are a fad, not a trend.

Rosalie said those who want a simpler burial can opt for a home burial. “If we’re going to have a home burial, perhaps we could plant a tree or a garden and use the nutrients decomposing to create new life.”

Rosalie first began thinking about different types of housings for corpses when she read an article about Latin American coffins that are made of papier-mache in the shape of things such as racing cars, Oscar statues or birds.

That sense of individuality and do-it-yourself attitude appealed deeply to Rosalie.

Heavily influenced by the back-to-the-land movement of the late 1960s and early ’70s, Rosalie grows most of her own food, carries no debt and lives off the electrical grid, getting by on a meager supply of electricity provided by a photovoltaic array.

Alison Rector, a board member with the Funeral Consumers Alliance of Maine, said shrouds are a natural extension of that lifestyle.

“Here in Maine we have the back-to-the-landers and people who want to do things like home births and growing their own foods,” Rector said. “I think those people here in Maine are also going to have a different kind of involvement with end of life.”

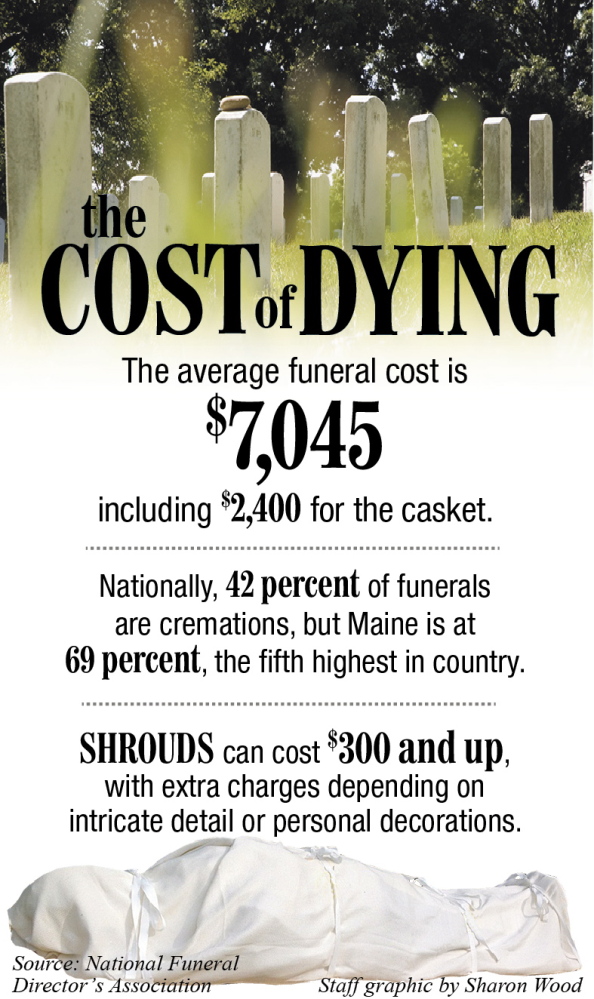

The costs of Rosalie’s shrouds vary, beginning at $300 and more expensive if intricate detail or decorations are included. Metal casket, cost $2,400 or more, and the vaults cost another $1,300.

END-OF-LIFE OPTIONS

The modern funeral industry wasn’t born until the Civil War, when the bodies of massive numbers of dead soldiers had to be shipped by rail over long distances. That created a public market for embalming fluid, sparking a cultural change that became the norm.

Once performed by family members in the home, the work to prepare a body for a funeral and burial began to be taken over by strangers behind the walls of funeral homes.

That sense of privacy continues to influence the culture of funeral homes today. Many funeral directors prefer not to comment publicly on issues such as burial alternatives, which they consider to be a sensitive topic.

Some members of the Maine Board of Funeral Service and the Maine Funeral Directors Association would not comment for this story.

Pat Lynch, past president of the National Funeral Directors Association, and a Michigan funeral director, acknowledged that decades ago funeral directors often did their work privately, partly because they thought it could traumatize grieving family members.

When a person died at a hospital, loved ones were told to leave the room while funeral staff collected the body.

Lynch does not defend that practice.

“For months, these people have been caring for her, holding her hand, bathing her, praying with her. All of a sudden they have to be shooed out of the room? That’s absurd,” Lynch said.

Rosalie said that culture made it easier to stop acknowledging and talking about death. The topic was taboo when she was growing up, she said.

“When did we stop talking about death?” she asked. “When the funeral directors and funeral homes started whisking people away.”

SHIFTING GROUND

There are changes happening in the funeral industry. Whether they are fundamental and widespread, or marginal and fleeting, is a matter of debate.

One change is green cemeteries, operated with environmentally friendly practices that encourage biodegradable coffins and forbid polluting agents such as embalming fluid.

Maine has two — Rainbow’s End Cemetery in Orrington and Cedar Brook Burial Ground in Limington.

“I was not aware until recently that most cemeteries in Maine require you to be in a vault. I had no idea,” Rector said. “There are tons and tons of concrete put into the ground each year.”

The tendency of the ground to settle is a particular problem in cemeteries because they typically use heavy equipment to mow the lawn and dig the graves, said Burrill, of the cemetery association, who has worked at Mount Hope Cemetery in Bangor for the past 45 years.

Green cemeteries use hand labor to dig and maintain graves, which allows them to avoid the use of concrete vaults.

Burrill said environmentally friendly funerals and alternative coffins aren’t a fundamental change to the industry; they’re just a current fad.

“It’s like a necktie,” he said. “It’s narrow, it’s wide, then it’s back to narrow.

“A trend is like anything. It might catch on for a while, and then it will do a 180 and people will come back the other way.”

The average cost of a funeral has increased 10-fold in the past 50 years, from $708 in 1960 to $7,045 in 2014, according to the National Funeral Directors Association. That figure includes a services fee of nearly $2,000, which represents a funeral home’s overhead costs, and $2,400 for a metal casket, as well as smaller amounts for things such as embalming, the use of a hearse and use of facilities for a viewing and a funeral ceremony.

It does not include the additional $1,300 for a vault, or items such as cemetery costs, gravestone costs, flowers and obituaries.

FAMILY FUNERAL

Today the very process of dying is more open than in the past.

Family members are more likely to stay in a hospice room as funeral directors arrive and make preparations to transport a body. During a funeral, family members sit with friends and witness. They may participate in the casket closing and sometimes help as the body is prepared and transported.

Lynch said that he and forward-thinking funeral directors around the country embrace the changes.

“There’s nothing that we will do that you cannot observe and take part in,” Lynch said. “Who better to do that final act of kindness to prepare somebody for their disposition?”

Lynch said that he and other funeral directors in his family have recommended things such as a grandfather building a coffin for his grandson, or five grandsons working up a sweat as they shovel dirt onto their grandfather’s casket.

“Did that bring some sort of comfort to know that this was very personal?” Lynch asked. “Of course it did. It’s not only appropriate, it’s beautiful.”

Lynch said he knows hundreds of funeral directors, the majority of whom agree with the open and participatory end-of-life arrangements.

“Any time a family can seek an alternative that meets their needs and addresses their concerns for treating their dead in a way that they find comforting, we clearly support such an endeavor,” he said. “If a shroud and a homemade box meets their needs in terms of bringing them comfort and peace, we would highly endorse that.”

Some families are now opting for home burial by family members.

Lynch said most people fall somewhere in the range from wanting to do everything themselves, including a home burial, to those who prefer to have the funeral home handle everything.

Inside the industry, he said, responsible funeral directors make sure that family members are aware of the full range of options they have and encourage them to choose what will be most meaningful for them.

BURYING A FRIEND

Rosalie made her first shroud for a friend who had been diagnosed with cancer.

When that woman died, Rosalie and other close friends prepared her body by washing it, dressing it and singing on the way to a backyard burial in a handmade casket.

One of those friends was Winnie Noyes, also of Thorndike.

After thinking about it, Noyes asked Rosalie to make another shroud, for when her time comes.

Rosalie said the shroud incorporates two piece of fabric that carry a special meaning to Noyes.

The first was a black-and-red blanket that she got while serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in Botswana in the early 1970s. The second is a silk sari that her grandmother had purchased while serving as a missionary in China.

“She will be tucked in with the sari laced in, and then the edges of the blanket will be folded over her,” Rosalie said.

A large thorn will be used to close the two corners of the blanket, a Batswanan tradition.

Rosalie said it gives her comfort to know that she can help to personalize the burial in a way that might ease the emotional fallout of another’s death.

Rector said she doesn’t know whether more people are turning away from mainstream funerals and metal caskets in favor of choices such as shrouds, handmade coffins or green cemeteries.

It seems to her that is the case, she said, but she acknowledged that her perception is skewed because she has spoken to so many people who have sought out those alternatives.

What’s important to her and the Funeral Consumers Alliance of Maine, she said, is that people acknowledge that their own death will happen, and understand that they have options available to them.

Rosalie said it’s never too early to start making final arrangements for one’s death.

“Figure out what you want beforehand,” she said. “That’s what the Funeral Consumer’s Alliance of Maine is all about.”

Rector says her own end-of-life plans are “a work in progress.”

“I fluctuate still,” she said. “I thought cremation was an environmental choice, but now I hear there are a lot of fossil fuels that go into making the fire. I’m beginning to get very interested in the green burial movement. I spent my whole life composting my veggies and foods, so why wouldn’t I compost myself?”

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling — 861-9287

Twitter: @hh_matt

Send questions/comments to the editors.