Federal officials will be in western Maine this week to discuss a proposal that could bring hundreds of jobs and 60 interceptor missiles to the remote mountains near Rangeley in the name of protecting the East Coast from nuclear attack.

The Pentagon is conducting environmental studies of four sites in the Eastern U.S. for an intercontinental ballistic missile defense system that has been pushed by Congress but may never be built because of tight budgets and performance issues with the interceptors.

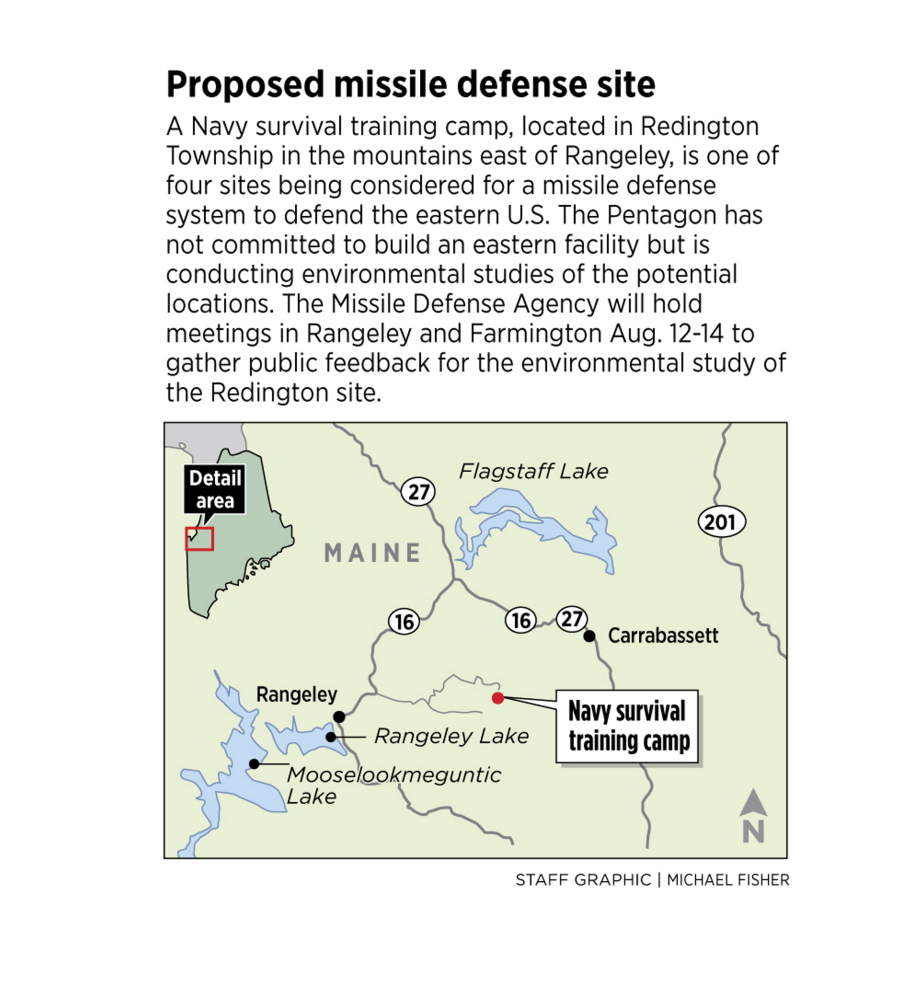

One of those sites is a little-known Navy training camp in Redington Township nestled between the Saddleback and Sugarloaf ski resorts. As the SERE School’s name suggests, the “Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape” School is where Navy SEALs, pilots and other select personnel go to learn how to survive in extreme conditions, avoid being captured, resist interrogation and escape their captors. The 12-day program features classroom instruction at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery and field training in Redington.

Whether the SERE School might have to share its space with silos housing 55-foot-long interceptor missiles — or could be displaced entirely — won’t be known for several more years. But representatives from the Missile Defense Agency will hold meetings in Rangeley on Tuesday and Wednesday, plus two more meetings in Farmington on Thursday, to gather feedback from the public about the environmental suitability of locating a facility in Redington Township.

Agency officials stressed that these are just preliminary studies for an as-yet hypothetical facility. The Defense Department has said that it does not believe another missile defense site is needed to protect the U.S. against current threats.

“There has been no decision to build an additional missile defense site,” said Rick Lehner, spokesman for the Missile Defense Agency. Instead, Congress ordered the Defense Department to conduct environmental impact studies of candidate sites so that construction could begin quickly in the event that the Pentagon decides a third interceptor site is necessary and Congress appropriates the billions of dollars necessary to build, staff and equip the facility.

The potential missile defense site is located in a rugged corner of western Maine where outdoor recreation is the primary economic driver. Sugarloaf and Saddleback ski resorts are both nearby but separated by several mountains. Rangeley and Rangeley Lake are roughly 10 miles to the west while the Appalachian Trail passes close to the site.

Despite the location, Fred Hardy, chairman of the Franklin County Board of Commissioners, said the topic hasn’t come up at the group’s meetings.

“Not at all,” said Hardy. Asked his opinion on the potential facility, Hardy said he was not opposed to an interceptor missile system in the county but wondered how much long-term employment it would generate after construction.

The United States is currently guarded by interceptors housed at two West Coast locations: Fort Greely in Alaska and Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

The current generation of ground-based interceptors do not carry explosive warheads. Instead, the interceptors are launched via rocket into space along the trajectory of the incoming missile. A separating “kill vehicle” then uses its own sensors, propulsion and outside guidance to crash into the incoming warhead. The Pentagon also operates another system, known as the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense System, that is based on Navy destroyers and cruisers.

The ground-based system — estimated to have cost taxpayers $40 billion so far — has a spotty record, however. Ground-based interceptors have failed to destroy their target in roughly half of the 17 tests conducted so far. The most recent test from Vandenberg Air Force Base in June was a success.

A 2012 report by the National Research Council found significant problems with the ground-based system but also warned of serious holes in the nation’s defense system against intercontinental ballistic missiles. The report recommended building a new type of interceptor system in either Caribou, Maine, or upstate New York to better protect the East Coast.

That report bolstered congressional support — strongest among Republicans — for another facility to protect the East Coast from potential nuclear threats from North Korea and Iran. Congress directed the Pentagon to evaluate potential sites and that list of hundreds was eventually narrowed to five: the Navy training school in Redington Township; Fort Drum in northern New York; Camp Ravenna Joint Military Training Center in Ohio; Fort Custer CTC in Michigan; and Camp Ethan Allen in Vermont.

Republican U.S. Sen. Susan Collins of Maine pushed hard for the Pentagon to consider the former Loring Air Force Base in Limestone, but the site was eliminated because the federal government no longer owns the land. The Vermont location was dropped from the short list, meanwhile, after all members of Vermont’s congressional delegation as well as the governor came out strongly against the project.

Tom Collina, research director at a Washington, D-C.-based nonprofit called the Arms Control Association, argued the environmental impact studies and field meetings are a waste of money on facilities that will never be built. Collina called the procedure “political theater” orchestrated by Republicans in Congress as well as Democratic lawmakers whose districts could benefit from the facilities.

“I think it is very unlikely given the budget pressure that Congress and the federal government are under right now but also because the systems we have on the West Coast are not doing very well,” said Collina, whose organization promotes “effective arm control policies.”

It’s unclear how many jobs such a facility would create in Maine. Alaska’s Fort Greely employs roughly 1,100 civilians and military personnel. However, the base also houses a Cold Regions Test Center and a Northern Warfare Training Center, according to the base’s website.

According to information supplied by the Missile Defense Agency, the future facilities could house up to 60 ground-based missiles and silos as well as offices, warehouses, staff living quarters, interceptor assembly building and storage facilities. The environmental impact studies of each site will take up to two years to complete and will examine the facilities’ potential impacts on air and water quality, wildlife and the local airspace. The study will consider the effects on quality of life in the nearby communities but will also examine the availability of water service, electricity and housing.

The Maine site appears to have some logistical challenges when compared to others on the list.

For instance, in Redington the buildings, silos and support facilities would have to be built in several locations on the site because of the steep terrain. The 55-foot-long interceptors would be transported from Bangor International Airport by road and parts of Routes 27 and 4 might need upgrades to accommodate the silos and other components.

Fort Drum in New York and Fort Custer in Michigan, meanwhile, each offer two potential sites for the facility and have airfields on site or local airports capable of accepting delivery of the interceptors. Custer also has Air National Guard facilities that could be converted to use for the missile defense system.

The Missile Defense Agency will hold scoping sessions in Maine this week in an “open house format” — rather than formal presentations with public comment periods — allowing visitors to talk with agency representatives individually. The meetings are scheduled for Tuesday, Aug. 12, from 6 to 9 p.m. at Rangeley Lakes Regional School; Wednesday, Aug. 13, from 9 a.m. to noon at Rangeley Lakes Regional School; and two sessions on Thursday, Aug. 14, from 9 a.m. to noon and 6 to 9 p.m. at the University of Maine at Farmington.

For more information, go to: http://www.mda.mil/about/enviro_cis.html;http://www.mda.mil/about/enviro_cis.html

Kevin Miller — 791-6312

kmiller@pressherald.com

Twitter: KevinMillerPPH

Send questions/comments to the editors.