AUGUSTA — More than 13 years since the paper making machines at the former Augusta Tissue mill shut down for the final time, city officials hope they finally may be on the verge of getting an environmental certification that will give potential developers the assurance they need to redevelop the riverside site.

A 2012 conceptual plan for the 32-acre city-owned site — also known as Statler Tissue — envisions it as being developed with a mix of retail, office and housing uses, featuring canoe and kayak launching areas and a city market something like a scaled-down version of Boston’s Faneuil Hall, with a train station serviced by passenger trains.

Rail advocates and city councilors have expressed interest in that type of development there, but, so far, the site has sat unused since the city, in 2009, had all but one riverside structure on the site demolished.

Pollution at the site, including PCBs from transformers that overflowed into the ground, has been cleaned up using a $400,000 federal Environmental Protection Agency grant and $80,000 in city matching funds, on top of about $1.4 million in previous EPA projects. The site contained about 100 55-gallon drums and tanks of chemicals used in the paper making process, and its wastewater treatment facility.

Keith Luke, the city’s deputy development director, said the site cleanup was largely completed in 2013, when PCB-contaminated soil was removed and oil-contaminated soil was capped in place.

Luke told city councilors Thursday that earlier that day he had received a draft of a certification letter from the state Department of Environmental Protection, outlining what the city needed to do to obtain the Voluntary Response Action Program certification for the site.

Luke said that certification is a key missing piece that could give developers assurance that if environmental contamination is found on the site, they would not be responsible for cleaning it up.

The certification, Luke noted, probably will come with deed restrictions on the use of groundwater and restrict development on capped portions of the property. However, he said those restrictions shouldn’t prevent the development envisioned by the 2012 consultant’s concept.

“VRAP is a certification the development community wants in hand before participating,” Luke said. “It alleviates their concerns about contamination that may be found at the site in the future. It effectively insulates developers from responsibility for cleanup for anything additional found at the site. This is what we’ve been waiting for.”

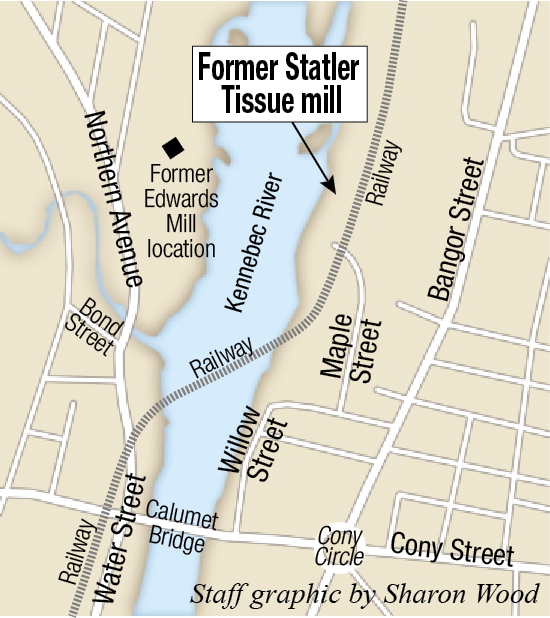

Ward 2 City Councilor Darek Grant, chairman of the Eastside Planning Committee, which included the former Statler site in its 2011 plan for the east side of the Kennebec River, said the city needs to step up its marketing of the site once the VRAP certification is finalized.

He suggested generating buzz for the site by inviting developers to tour the spot and using the 2012 consultant’s report by Eaton Peabody to give developers an idea of what the city has in mind for it.

“Let’s hear from the developers, the experts, as they tour the facility and identify the challenges they see,” Grant said. “Reach out to developers around New England, around the country, and say, ‘This is what we have. We’re open to suggestions. And we want development here.’ I’d be open to hearing any kind of developer come forward with an idea so we can see that site become useful again.”

The mill, also previously known as Hudson Pulp and Paper, operated at the site for more than a century, employing hundreds of local workers.

The city acquired it for nonpayment of taxes in 2009.

In 2012 the city, looking for a more positive name for the site other than that of a former mill, redubbed it Kennebec Lockes. An old lock designed to help boats navigate the river is still on the site.

Luke said the city will have a small amount of money, $5,000 to $10,000, in next year’s budget to market the site.

City Manager William Bridgeo said city officials have had some discussions with the operators of OneSteel Recycling, which is off Willow Street next to the mill site, about working with them to move the steel recycling business, freeing up that site to provide better access to Kennebec Lockes.

The site’s only public access now is off Maple Street, a street lined with residential homes. Bridgeo said the city is sensitive to Maple Street residents’ wishes that their residential street not become the main public access point for a major development.

Leaders of Maine Rail Group, a nonprofit group that advocates for rail transportation, spoke to councilors last month about passenger train service returning someday to Augusta, probably from Brunswick.

Richard Rudolph, a director of Maine Rail Group and chairman of Rail Users Network, a national organization focused on passenger rail service, said the former Statler site could make an excellent regional passenger train station location, drawing passengers from areas including Waterville, Bangor and Camden to Augusta to board the train.

Jack Sutton, former president of the Maine Rail Group, suggested the Augusta site even potentially could be the location of a train layover facility, where trains could be kept overnight when not in service. A proposed layover facility in Brunswick has been controversial, as neighbors have complained about the potential for noise from trains parked there. Portions of the Kennebec Lockes site are not near residential neighborhoods.

At-Large Councilor Dale McCormick said she believes development tends to follow transportation, so the city should look at making the Kennebec Lockes into a regional transportation hub.

Luke, echoing previous comments by Sutton, said restoring passenger rail service to Augusta, while possible, would take a long time and would need additional funding sources.

Luke said other than the discussion with the rail advocates, the city has not had any significant interest expressed in redevelopment at the site.

Luke said the city is fortunate compared to some municipalities that have cleaned-up sites they’d like to see redeveloped, in that most of the cleanup was paid for with EPA money, so the city didn’t have to go into debt to get the spot cleaned up.

“A lot of these situations, you’d have a $1 million bond to pay back, pressuring us to quickly get a return on that investment,” he said. “Here, the carrying costs were very low. There is no debt. Hopefully, we won’t have to wait too long, but we don’t have that debt hanging over us. We can wait for the right opportunity for Augusta.”

Keith Edwards — 621-5647

kedwards@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @kedwardskj

Send questions/comments to the editors.