Concerns that a city program was sending the wrong message about drug use when it gave out a powder to mix with crack cocaine will not stop the public health effort, just change the way the powder is packaged.

The Portland Needle Exchange program no longer will include written instructions attached to the vitamin C powder it provides to some intravenous drug users, responding to resident concerns that the labels might imply the drug use was safe.

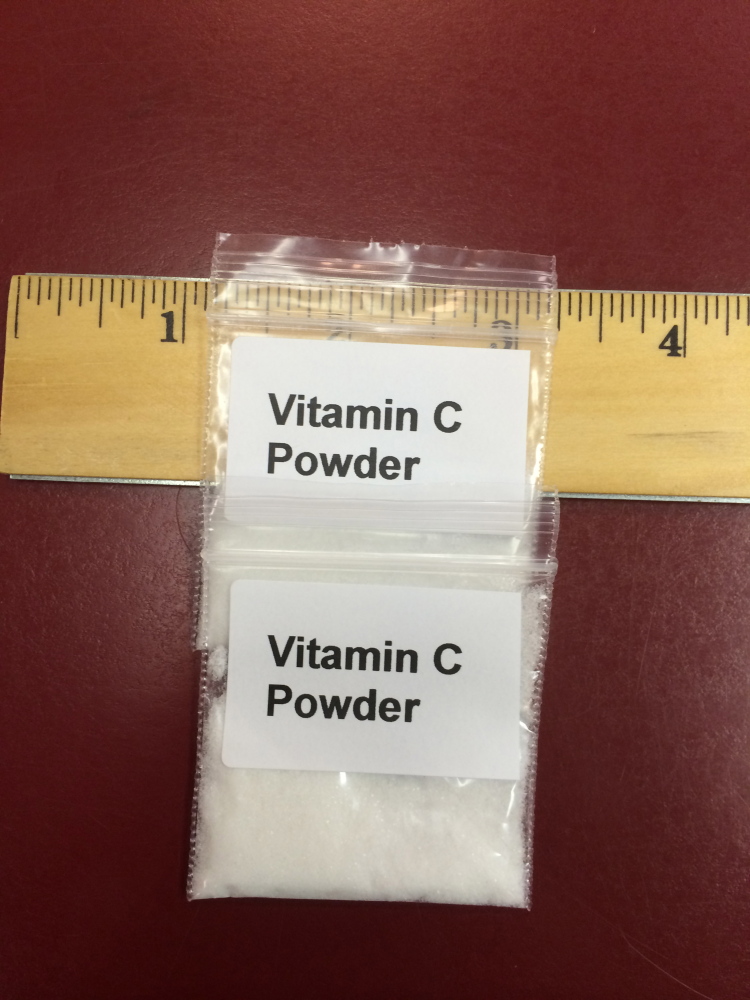

The program distributes about 50 small packets containing the vitamin powder a year, and until recently it included instructions for how to use the powder when turning crack cocaine into a liquid so it can be injected. The goal of the program is to get drug users to stop relying on more common but dangerous ingredients they use to prevent infections when they shoot up. The packet labels pointed out that vinegar or lemon juice can cause vein damage.

The packets of “Breakdown Powder” are distributed along with vials of sterile water, clean cotton swabs and other disposable supplies aimed at reducing the frequency of infection. But it was the wording on the vitamin C that irked members of the Bayside Neighborhood Association after the label was found in the neighborhood.

“These kits imply that shooting up is safe, as long as this powder is used,” said a letter to city officials from the association’s president, Stephen Hirshon, and Neighborhood Watch co-chairwomen Laura Cannon and Cindy Bachelder. “This is a very dangerous message for IV drug users, recovering users, at-risk members of the community, and impressionable young people.”

Similar criticisms have accompanied similar public health efforts, including the distribution of fliers telling addicts how to use heroin in a way that reduces the chances of overdose deaths.

City officials say they are not trying to facilitate drug use but to reduce the harm caused by abuse, giving people a better chance of getting treatment and leading productive lives. Distributing the powder is part of a broader harm reduction strategy that is the basis for the needle exchange program.

Re-using and sharing needles and other intravenous drug paraphernalia can lead to transmission of HIV and Hepatitus C. That, in turn, leads to pain for the users and their families as well high medical costs for society when those people show up in the emergency room.

“One case of HIV disease costs $675,000 in lifetime medical care costs,” said Caroline Teschke, program director, adding that the 200,000 needles a year it distributes costs the program $15,000. “Even if you don’t like our philosophy, you ought to like our economics.”

The powder is given to crack cocaine users based on similar reasoning. Using lemon juice or vinegar to dissolve crack cocaine can cause fungal infections in the blood, abscesses and bacterial infections that can be expensive to treat.

The city program, located on India Street, has been enrolling addicts in its needle exchange program for more than a decade. The program also administers tests for HIV and hepatitis C and immunizations for hepatitis A and B.

The program enrolled a total of 625 people last year and collects and distributes 200,000 needles over the course of a year.

Throughout most of that period it also has distributed the vitamin C packets, but in much smaller numbers.

Julie Sullivan, acting Health and Human Services director for the city, says the program gives out on average just a single packet a week because intravenous crack cocaine use is nowhere near as commonplace nor as severe a public health problem as intravenous heroin use. The overall cost to the program: $20 per year.

Needle exchange programs across the country routinely distribute the vitamin powder to those users who request it, and distribution is listed as proper practice in “A Safety Manual for Injection Drug Users” published by the Harm Reduction Alliance, a national group.

But the city program has changed the labeling.

The packets used to read: “Breakdown Powder for crack cocaine. To minimize vein damage instead of vinegar/lemon juice, mix one pinch of powder with rock and plenty of water. Use a clean needle each time and dispose of all equipment in a biohazard box.”

Now the packets say simply “Vitamin C,” and workers at the needle exchange program will spend a few minutes instructing users who request the powder how to use it properly.

“We’re not going to stop giving out the powder. We’re going to find a way of not giving instructions actually on it,” Teschke said. “We’re very motivated to be good partners here. We want people to support us and be our community partners.”

Laura Cannon, one of those who wrote the letter, said the association has supported the work of the program and recognizes the seriousness of the drug problem and the need to address it. However, she said, it’s important that efforts to keep people healthy are really working to get them off drugs.

“These kinds of harm reduction programs are really intended to be part of a continuum of services provided by users,” she said. “It’s really unclear to me what the path is for addicts and users in Portland, what the path to recovery is.”

City officials agree that one of the challenges to the program being successful is having affordable treatment options for users.

Under current MaineCare rules, single men and women who are not pregnant or caring for young children are typically ineligible for government benefits that would pay for treatment, Sullivan said. Also, there are not enough treatment spots, she said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.