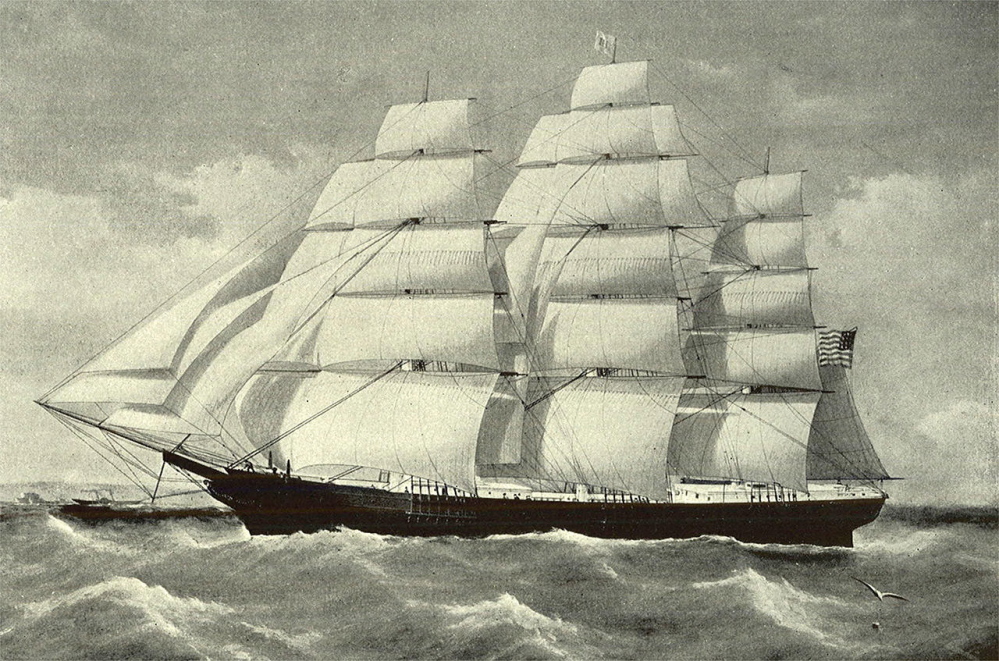

Noonday sank in 1863, becoming one of 300 wrecks on littering the seabed west of San Francisco

A clipper ship built in Maine that sank off the coast of California 151 years ago has been found buried on the ocean floor just west of San Francisco.

The Noonday, a clipper ship built on Badger’s Island in the Piscataqua River in 1855 to haul cargo to California during the Gold Rush, was found mired in mud by an expedition of marine archaeologists. The scientists were on a five-day survey with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that ended Monday and discovered the sites of at least four wrecks, including the 1863 wreck of the Noonday.

Built for speed, the ship was under full sail bringing general cargo to San Francisco on New Year’s Day in 1863 when it struck a submerged rock as it approached San Francisco Bay. The ship, carrying cargo valued at $450,000 — about $8 million in today’s currency — quickly took on water and sank. The crew survived and was picked up by a boat that had been two miles away.

The rock that sent the Noonday to its grave was covered by 18 feet of water. While local pilots knew its location, the rock was not marked on navigation charts at the time. Today’s charts identify it as Noonday Rock.

The waters just west of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge hide a graveyard of sunken ships. By some estimates, there are 300 wrecks in the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary and the Golden Gate National Recreation Area alone. Only a fraction of them have been seen by scientists.

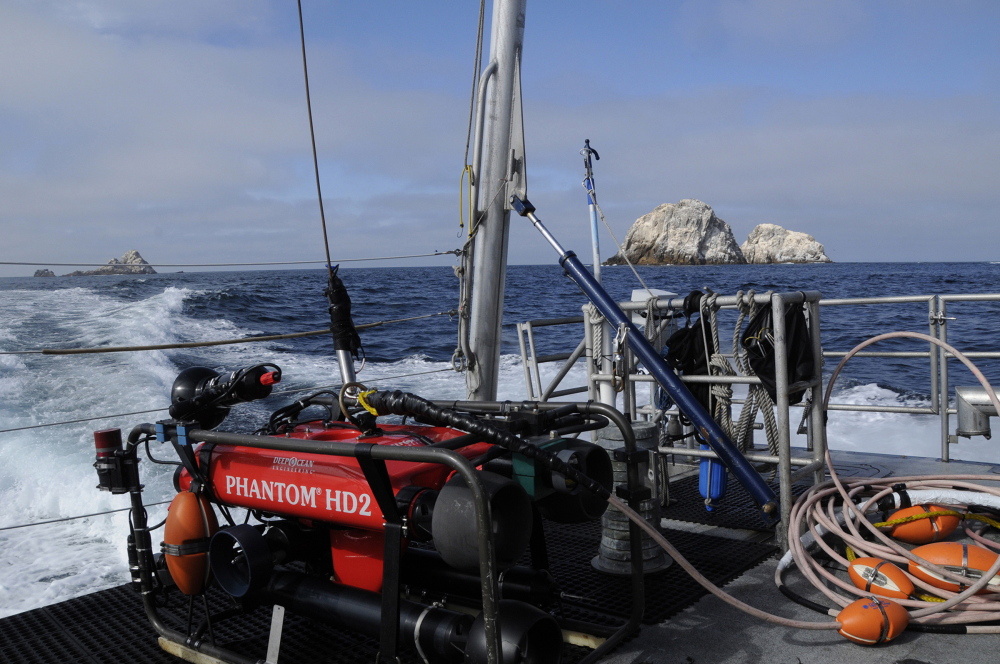

The researchers found the Noonday with the help of a remote-controlled submarine equipped with sonar and video that allowed them to see underwater video footage in real time.

Sonar revealed the outline of what appeared to be a clipper ship, but the researchers couldn’t see any physical remains of the Noonday, leading them to believe it was buried under sediment. The sonar signal data indicated the ship was the right size and in the right location for Noonday. It was found about 240 feet below the surface.

“Noonday is there. The sonar is very clear. But there’s just nothing sticking above the seabed,” James Delgado, NOAA’s maritime heritage director, told the Associated Press. There are no plans to excavate the site.

The expedition was part of a long-term archaeological survey of the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, which covers about 1,300 square miles of the Pacific Ocean off the Northern California coast.

The Noonday, which had a hull length of 197 feet and could carry 1,500 tons of cargo, was a mid-sized clipper ship, said Nathan Lipfert, senior curator at Maine Maritime Museum in Bath.

It was built on Badger’s Island, which motorists on U.S. Route 1 travel over as they cross the river between Kittery and Portsmouth, N.H.

Before the Civil War, Badger’s Island was home to the busy Fernald & Pettigrew Shipyard. Because of the island’s gradual slope into a deep river channel, it was ideal for launching vessels. Eastern white pine for masts and other lumber arrived via the Piscataqua River from inland forests.

From 1851 to 1855, the shipyard built eight clipper ships. The Noonday, the yard’s last ship, probably got its name because the previous ship built on the island was called the Midnight. The yard’s other ships had more dramatic names, such Typhoon, Dashing Wave and Water Witch.

The Noonday was built for Henry Hastings, a prominent Boston merchant. Its exterior hull was painted black. Emblazoned on the headboards at the bow was its name in gold letters, and gilded carved woodwork of an American flag and eagle adorned its stern.

In the mid-1800s, Maine built more ships than any other state. Clipper ships — the fastest commercial sailing ships ever built — had become a popular design during the Gold Rush because of the demand for commodities in booming California. Just about any product shipped to California could be sold quickly at high prices, Lipfert said.

Because clipper ships were faster, they could make more trips and produce more profits for their owners, Lipfert said. Compared with ordinary cargo ships, clippers carried an exceptionally large spread of sails in proportion to the size of their hulls, and had sharper bows that cut through the seas. Crews of 25 to as many as 100 men worked to position the sails to optimal effect.

When it came to their design, economy and long life were literally thrown to the wind for the sake of speed.

The clipper ship Northern Light, for example, in 1853 sailed from San Francisco to Boston in 76 days, six hours — a record for single-hull sailing vessels that stands today. However, that same design reduced the cargo capacity, which increased the cost of moving goods and made the ships less safe, Lipfert said.

Close to 90 clipper ships were built in Maine, largely for out-of-state owners. The more conservative Maine ship owners preferred building traditional vessels for themselves, Lipfert said.

Sure enough, the economic conditions that powered the era of clipper ships were short-lived. The depression of the mid-1850s, which culminated in the Panic of 1857, reduced demand for freight and dampened the urge for speed. Sailing vessels faced a growing challenge from steamers, which, unlike sailing vessels, could keep a tight schedule.

The sad demise of the Noonday was not an unusual end for commercial ships of that era, Lipfert said.

“Wooden sailing vessels tended to be used until they were used up, so it was frequently a bad end,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.