Some evening this October when the weather forecast calls for clear skies, William Balch and three other researchers from the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences will drive a truck into the belly of the Nova Star ferry.

The truck carries a 20-foot container that serves as their laboratory.

“We’re using the ferry as an ocean research vessel,” said Balch, a senior research scientist at Bigelow, based in East Boothbay.

Bigelow researchers have been taking water samples along the path of the ferry route since the late 1970s, when they threw buckets overboard the MV Marine Evangeline.

Their findings are adding crucial data to the study of climate change and perhaps offering a sobering view of what could be the future of Maine’s fisheries.

The return of ferry service between Portland and Yarmouth after a four-year hiatus means it’s easier and less expensive for researchers to continue collecting samples on the 207-mile-long straight line across the Gulf of Maine and to maintain the longest-running sampling program in coastal waters in the United States.

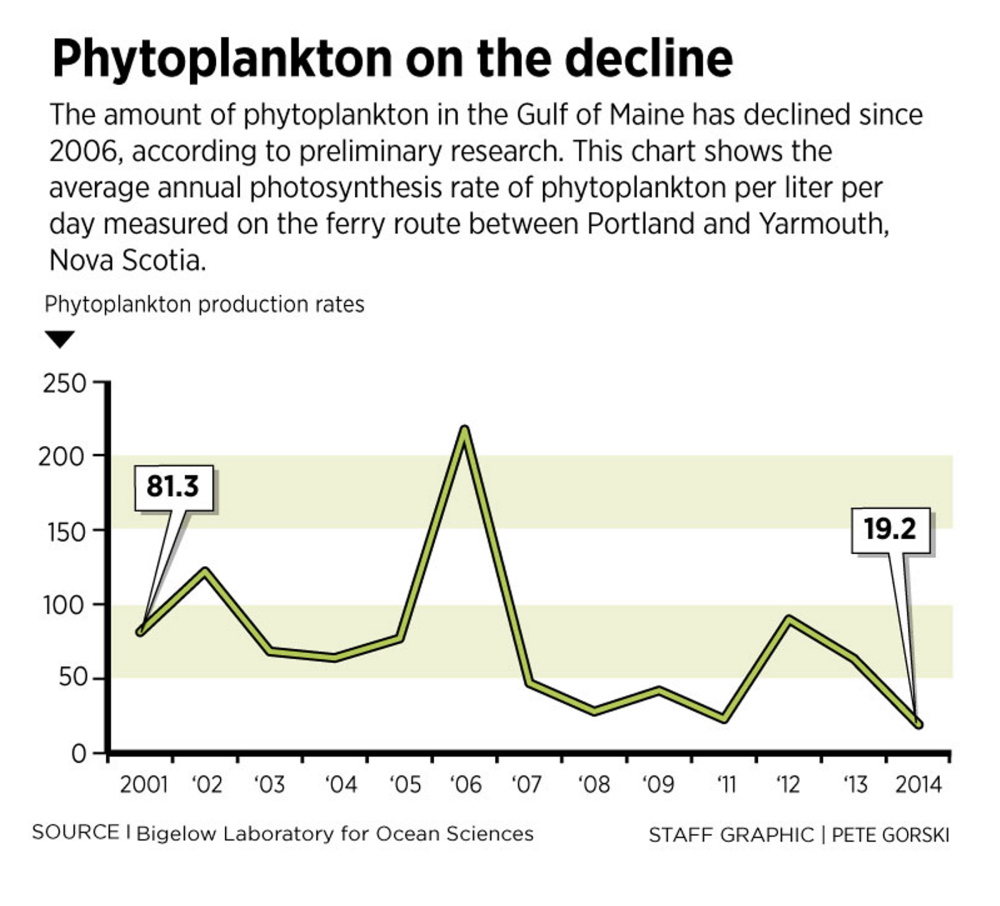

In recent years, the researchers have measured a fivefold decline in the growth rate of phytoplankton, the critical single-celled plants at the bottom of the marine food chain.

Because phytoplankton are food for fish larvae, a lower abundance of phytoplankton could mean lower numbers of adult fish populations years from now, Balch said.

Since the Nova Star began operating on May 15, Balch and his team have made five trips to Yarmouth and back.

The data collected this summer shows the lowest growth rate of plankton the team has ever recorded.

Rather than throwing buckets overboard, the scientists collect samples from water that flows through a small opening in the ship near the bow and is pumped into their laboratory while it sits on a truck parked on the ferry’s vehicle deck.

The researchers did the same thing on the Scotia Prince and the Cat, predecessors of the Nova Star. From 2010 though 2013, when there was no ferry service, they continued to collect data along the same route using small research vessels and lobster boats. Since 2008, they have also deployed robotic miniature submarines that travel at a speed of about a half a knot as they glide across the Gulf of Maine on battery power.

The data collected along the ferry route includes water temperature, salinity levels and the composition of nutrients. Scientists call this kind of data collection a “time series” because the data are obtained over a period of time. While researchers also use buoys to collect data in the gulf, this is the only data set in the region that covers a large area, said Andrew Thomas, an oceanographer at the University of Maine.

Moreover, Balch enters the data into a national database so all scientists can access it to carry out their research, Thomas said.

While the data itself is basic, it increases in value as time passes because it allows scientists to observe changes in the environment, such as those caused by climate change, said Andrew Pershing, the chief scientific officer at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute in Portland.

“It’s really sort of priceless,” he said. “What is amazing to me is how much effort and dedication it takes to get the time series working for this long a period of time.”

The project is funded by NASA because the Bigelow data is used to validate the data collected by Earth-observing satellites. Those satellites measure the chemical and organic composition of the world’s oceans by quantifying wavelengths of light bouncing off the ocean surface.

The ferry operation across the Gulf of Maine gives researchers a huge advantage because it is much less expensive than relying on research vessels or fishing boats, Balch said. Additionally, research vessels must be scheduled years in advance. A stretch of bad weather could ruin a whole trip, since data collection occurs only under clear skies. The satellites can’t make measurements when it’s cloudy. Because the Nova Star makes daily runs, Balch said, he can use weather forecasts to determine when the skies are clear enough for a trip.

“The ferry is the reason we can be out there on clear-sky days,” he said.

Pinpointing collection days enhances Bigelow’s ability to collect data. It supplies NASA with about 20 percent of its validated ocean observations.

Balch collects the data during the ferry’s daytime journey from Yarmouth to Portland, since the satellites make measurements within a couple hours of noon. He and three colleagues work in the cramped laboratory during the entire passage.

The researchers have found some interesting trends. In 2012, Balch published a paper that documented the fivefold decline in the growth rate of phytoplankton, the critical single-celled plants that ultimately support the region’s fisheries.

The paper concluded that well-above-normal annual rainfall that occurred between 2005 and 2009 had sent a surge of fresh water and sediment into the gulf. The increased river discharge appears to have prevented deep, nutrient-rich North Atlantic water from entering the gulf, according to the study. At the same time, the runoff flushed more dissolved organic matter in the water, reducing the amount of light available for phytoplankton growth.

After 2009, annual rainfall was closer to normal. In 2012 and 2013, the growth rate of phytoplankton partially rebounded. Based on measurements this year between June and September, however, the growth rate of phytoplankton is on pace to be the lowest since 2001, the year Bigelow started measuring the rate.

Balch said the changes now occurring at the bottom of the food web in the Gulf of Maine are complex but significant, given how they can affect adult fish populations in years to come.

A time series that takes place over many years is the best way for scientists to understand these connections, he said, so he plans to keep collecting data as long as possible.

“As long as the ferry keeps on running,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.