• THE COLLEGE STUDENT

It took just one not-so-great year at St. Lawrence University in New York for Yarmouth native Olivia Conrad, 19, to accrue about $25,000 in debt – a serious wake-up call about paying for college.

“I kind of understood it … (but) I feel like I should know more about how my college is being paid for,” said Conrad, now a sophomore biochemistry major at University of Maine in Orono, where in-state tuition is a fraction of St. Lawrence’s $60,000 tuition and fees. “When you are my age and starting to apply to college, all you are thinking about is where to go, not how to pay for it.”

Crunching the numbers on what she’ll have to pay back is “kind of a reality check.”

After calculating her debt from her freshman year alone, she’s pared her expenses down to the basics at Orono, renting a place off-campus, not participating in a meal plan, and spending the summer working to save up rent money.

It’s sobering, but part of growing up, she said.

“You go from being a high schooler, and not having to pay for it, and suddenly you are faced with having to pay for such a huge thing,” she said.

The student loan debt she’s already accrued, she says, “takes away your ability to be carefree.”

“I’m always thinking about a job. Thinking about paying off that debt,” she said.

“But everyone is in the same boat. In this day and age, that’s the situation for most people. You just have to roll with it.”

• THE PARENTS

With two sons in college and a third in high school, Sheri Clark Nadell of Brunswick is honoring a vow she made that her children wouldn’t graduate with student debt. She and her husband, Paul, are paying for their undergraduate education.

So far, that vow has cost them about $60,000, and they still have their youngest son’s tuition ahead of them.

“I don’t even know the exact amount (of debt) because if I did, I’d start to cry,” said Nadell. “But we can’t complain. We’re middle-class, incredibly blessed and we are both employed.”

At one point, Sheri and Paul were unemployed at the same time while still paying two college tuitions.

“We sort of took a big gulp,” Nadell said, adding that at one point they had to take out loans against their house and have family members help them out.

But that’s still better than having their sons take on the debt and graduate with huge student loan bills to pay, she said.

“It’s not OK, these kids coming out of college with all this debt,” she said.

“It’s got to stop. It has to level out at some point,” she said of the sharp increase in tuition. “It’s not increasing at the rate our salaries are increasing. Not by a long shot.”

• THE PROFESSOR

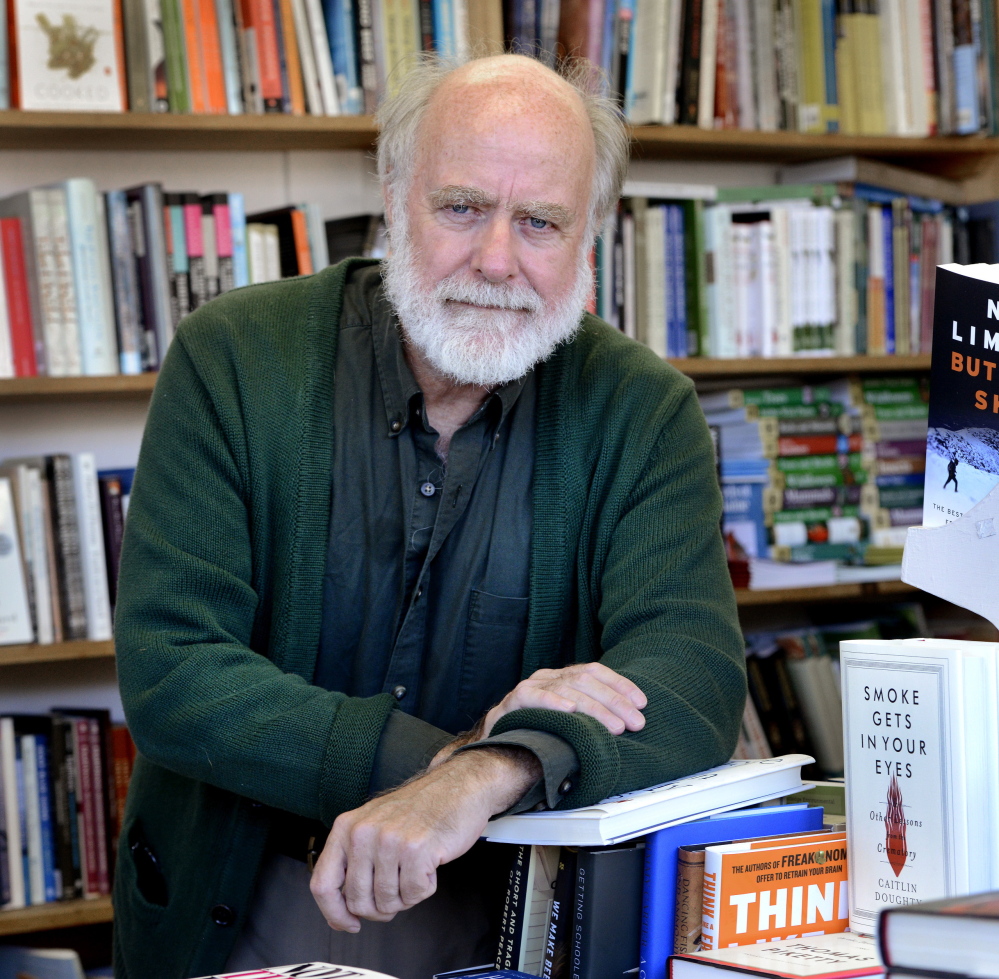

Going back to college as a 40-year-old, Barry Rodrigue had a plan to get a double Ph.D. in order to land a dream job. To an extent, it worked.

But it took a decade of school and $180,000 in student loans to get those degrees: a master’s in history from University of Maine, a Ph.D. in geography from Universite Laval in Quebec and another Ph.D. in historical archeology and history from UMaine.

Rodrigue, a Fulbright scholar, was hired right out of graduate school by the University of Southern Maine in 2000, but the student loan payments ate up about 40 percent of his $33,000 paycheck, burdening his young family.

“It was a huge drain on our household finances,” said Rodrigue. The payments have eased in recent years, with legislation that capped payments based on income, so now his payments are about 10 percent of his income.

But his debt still hovers around $180,000 because the payments just service the interest.

And as of last month, he’s out of a job.

Rodrigue, an associate professor of arts and humanities, is one of the seven professors laid off after the trustees cut three academic programs at USM last month.

Student loan payments can only be deferred, never discharged, even in bankruptcy. A recent federal report said an increasing number of retirees are seeing their Social Security garnished as they carry federal student loan debt into retirement.

Meanwhile, Rodrigue is trying to figure out how to pay his own debt, and if possible, help out his college-age son, who has $20,000 in college debt of his own.

“We’ll deal with it,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.