The name on the stationery’s letterhead read D. Bradford Park, a retiree living in Maine. He was asking for help. A newly purchased pellet stove was no longer heating his lakefront home.

A copy of the letter, addressed to Maine’s Attorney General, was sent to the Maine Sunday Telegram with a note of explanation. Yes, the man admitted, he once played hockey.

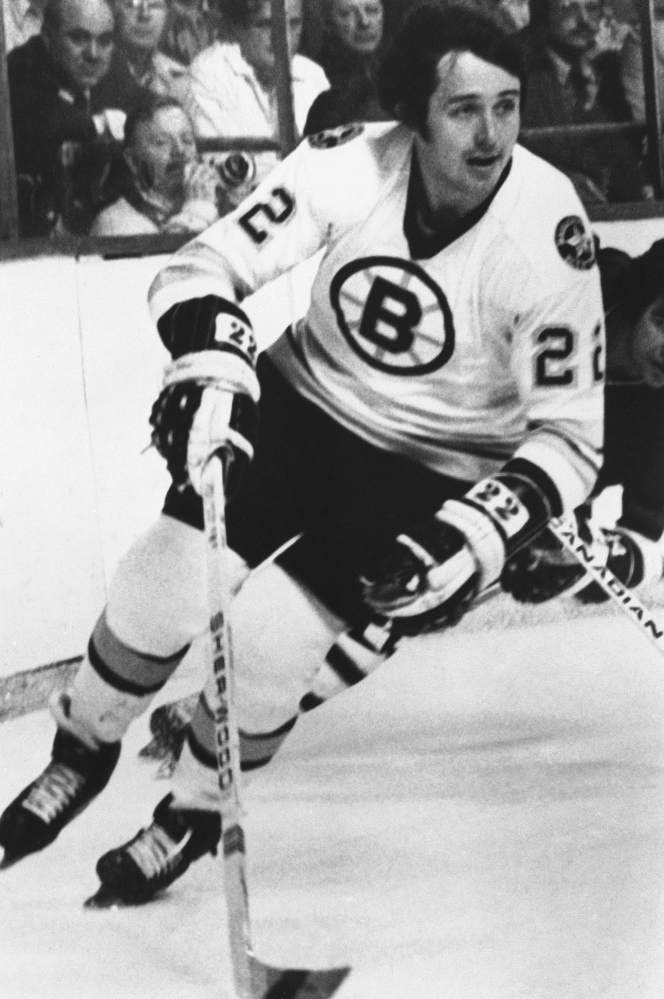

Wait. Could this be Brad Park, the defenseman who followed Bobby Orr into the hearts and minds of Boston Bruins fans in the 1970s soon after he was traded from the New York Rangers? The same Brad Park who was elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility in 1988?

Yes, it turns out that the Brad Park has been living inconspicuously on the western shore of Sebago Lake for parts of 30 years with his wife, Gerry, and their five children.

“Maybe my name still has a little juice,” Park said recently at the home he calls his cottage. “I didn’t want to use it. I’m just like any working stiff who bought something and it’s not right. Just call me a consumer.”

For hockey fans of a certain age, Brad Park was second only to Orr as the best defenseman who ever skated onto rink ice. He played when very few wore helmets and faces were as familiar as the numbers on their backs. “No one recognized me on the streets when I played in New York. You had Broadway and actors and actresses,” Park said. “When I came to Boston it was different. My wife would walk with me and say I looked distracted. I was. I thought people were looking at me.”

Born and raised in the Toronto area, he didn’t understand fame.

Now he is 66 years old and content that his past is, well, his past. He last played in 1985, a long time ago. During his career, he traveled and saw many cities, many places. The beauty of this spot on the Sebago Lake waterfront kept luring him back. “I love it here.”

His two-story home spreads out over a relatively small lot, maybe 20 yards from the water. The place is comfortable with no hint of pretense. Practically nothing indicates it is home to a hockey legend.

“It’s bad enough my kids had a hockey player for a father,” Park said. “I didn’t want them to have to live in a shrine.”

One bit of his past hockey life is visible. Propped against a wall is an oil painting of three players in New York Rangers uniforms. “Only three of those in existence,” Park said. “Can you name the players?”

Park, only 20 years old and in his rookie season was in the middle and easy to identify. Walt Tkaczuk, a fellow rookie and still a good friend, was on the left. The player on the right wasn’t as recognizable. “Bill Fairbairn,” said Park. Fairbairn’s rookie season was a year later. He and Tkaczuk were linemates.

“I made $10,000 my rookie year,” Park said, smiling. “I got a summer job working at hockey camps. They were new back then. I worked construction jobs before I came to New York.”

The pay got better, although not by today’s standards. The Rangers bumped Park to $14,000 and $30,000. Then came the windfall of $200,000 to keep him away from the World Hockey Association, the new and short-lived rival to the NHL.

The point is, he is not a wealthy Hall of Famer. “I couldn’t buy this today,” he said, standing outside his home. He has split time between Maine and the family home in a suburb north of Boston. The Parks usually button up the camp after celebrating Christmas here. The house in Massachusetts is in the process of being sold, and Brad and Gerry, his wife of 44 years, will relocate to Florida for the coldest winter months. Gerry has just retired as the registrar at a nursing school in Boston.

“He’s aces, just a regular guy,” said Frank Bathe, a fellow defenseman who played for the Maine Mariners and Philadelphia Flyers near the end of Park’s career. “A real, down-to-earth guy. You’d never know what he did on the ice.”

Bathe, with his red hair and full red beard also was a Canadian, growing up in the province of Ontario. He was a fan favorite in Portland. After a back injury forced the end of his NHL career, Bathe returned to the Portland area. He’s never left. He knew Park lived in Sebago. They’ve played golf together many times at the Gorham Country Club over the years.

“He’s always complaining about his knees,” Bathe said. “Then he steps up and drives the ball 250 yards, beats me and takes my money. A real sandbagger, but a great guy. He doesn’t call attention to himself. He’s the best.”

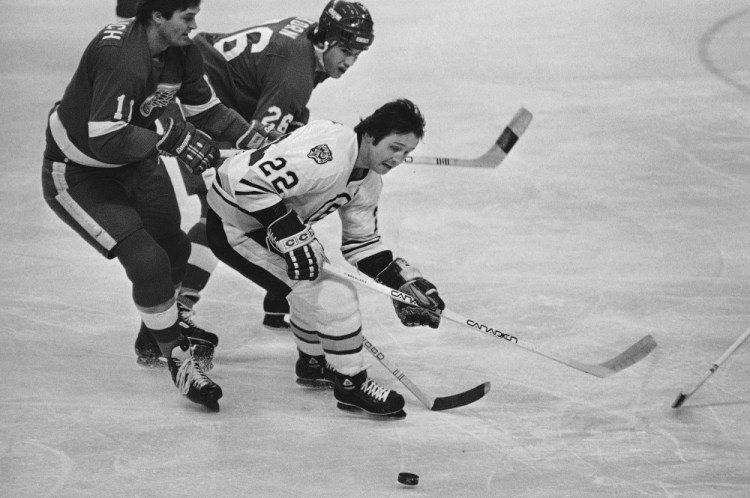

Park played 7 1/2 seasons in New York, 7 1/2 in Boston and two in Detroit to finish off his on-ice career. The Nov. 7, 1975, trade that sent him from one of the NHL’s original six hockey cities to another was shocking. Park and Jean Ratelle and Joe Zanussi for Phil Esposito and Carol Vadnais. The Bruins wanted Park because Orr’s knees could no longer hold up for a full season. In Esposito, the Rangers were getting one of hockey’s best scorers.

When Park called his wife with news of the trade he broke down. He loved New York. In time, Park and his wife embraced Boston. Bruins fans eventually did the same with Park.

He had knee replacement surgery a few years ago. He no longer skates in alumni games. He still gets asked to make appearances to speak, sign autographs. He doesn’t watch a lot of hockey. He doesn’t like crowds and tends to critique the game more.

“If it’s an appearance I’m signing autographs and I can’t watch much of the game. If I go to the alumni box people always want to talk and I miss a lot of the game.”

He watches hockey on television but finds himself switching to something else. He thinks there’s less offense in the game today and this is a defenseman talking. Skills are less defined and he explains how the blades on today’s sticks have less flex and how players must start their swings farther behind the puck to get flex from the shaft of the stick.

That cuts down on accuracy, he said. The best and true wrist shots are a thing of the past. Goalies are bigger, wear larger pads and aren’t intimidated as easily.

“A three-on-two (breakaway) will always be a three-on-two will always be the same, but the philosophy of the game has changed,” Park said. He speaks matter-of-factly, understanding that everything evolves.

As he spoke, Cooper, his young golden retriever, vied for his attention. Let’s play. Park simply grinned at Cooper’s persistence. Behind Cooper were the glass doors to the deck outside. Park had positioned his chair so he could see the angry lake waters.

He has pride, but his ego is difficult to find. “When you get punched in the face in front of 17,000 people you better have some humility. It’s the way you were brought up. We weren’t put on a pedestal.”

When Park runs errands to Windham or Standish he reaches for a baseball cap and pulls the bill low over his eyes. The right of way to the lake runs along his property. His many neighbors walking to the water wave to the man who enjoys sitting on his deck. Hiya doing, Brad. Beautiful day, isn’t it.

“People think I’m a private person,” Park said. “They wouldn’t say that if they saw me outside in the summer.”

The $2,000 pellet stove bought online through The Home Depot sits in his garage. A $1.49 cotter pin holding the collar that connects the auger to the electric motor has broken more than once. A replacement cotter pin came in the mail but according to Park neither the manufacturer nor the store said they were responsible for taking apart the stove to replace the pin.

Park wanted to return the stove but was told the three-month period to do so had past. He bought the stove in July two years ago and didn’t use it until that November. When the Parks closed up their home by the lake after Christmas the stove was shut down. It wouldn’t work when they returned months later in the spring less than a year after it was purchased.

As of late October, Park said the matter had not been resolved. He’s stored the stove in his garage and bought another from a local dealer.

He wrote a letter of complaint to the consumer affairs arm of the state Attorney General’s office in Augusta and got a response. He has a form to complete and return. In the meantime, he says, he may load the stove in his pickup, drive to the Home Depot store in Windham and dump it on their doorstep. “It’s of no use to me. Let them have it.

“I could replace it. What about the guy who can’t because he doesn’t have $2,000?”

Stephen Holmes, The Home Depot’s Director of Communication in Atlanta, said someone from the company’s consumer support would be contacting Park soon. He said their records show they made attempts to reach him in June without success. Holmes is a golfer and from Mississippi and confessed he doesn’t know hockey, D. Bradford Park or Brad Park. Which is exactly how Park wanted to be treated.

Last week, The Home Depot did reach Park.

Steve Belanger owns a pellet stove business in Standish and installed the first stove and the replacement stove. He’s not a hockey fan. He had no idea who his customer was until someone told him. “I respect that he was a professional hockey player, but I wouldn’t want that job,” Belanger said. “But he doesn’t push who he is on anybody. I’ve been to his house a number of times trying to get the first stove to work right. We’ve talked. He’s down to earth about everything.”

In September, Park was asked to drive the pace car at the NASCAR Sprint Cup race at New Hampshire Motor Speedway. It was an honorary position. He was behind the wheel of the pace car once during the warm-up laps before the green flag dropped to start the race. The regular pace car driver went onto the track afterward to help reform the field after cautions.

It was Park’s first time at a Sprint Cup race. He noted that the Brad Keselowski, driving the No. 2 car, qualified for the first row, or pole position. “That was my number with the Rangers.” He didn’t seem aware that Keselowski, to use a hockey term, has been quick to drop his gloves and mix it up with fellow drivers on the track and off. But then, Park didn’t have that reputation.

Joey Logano, in the No. 22 car won the Sylvania 300. “That was my number in Boston.” Park said with a grin. He enjoys the little connections.

Park was introduced to the large crowd of some 80,000, heard the cheers and waved. He stood in a receiving line of sorts when each driver was introduced. “They were so young,” said Park. “One said something to me. Jeff Gordon. He said he was at the Hockey Hall of Fame (in Toronto) and saw me.”

Meaning he saw a likeness of Park or the hall of fame plaque.

“I asked him if he threw anything at me,” said Park. He chuckled again. It was the sound of a man who can laugh at himself.

Send questions/comments to the editors.