It turns out this past summer was the hottest ever measured on Earth.

Here in central Maine it did not seem unusually warm, apart from a couple of spells in June and July. In fact, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has maps that indicate the high temperatures for the Northeast United States were near average this summer. Some places you normally think of as being choking hot much of the summer, like the Dakotas and Missouri area, were actually a bit cooler overall than usual. Things went along pretty much as usual.

On the other hand, the West was much hotter than the average of temperatures recorded since 1895.

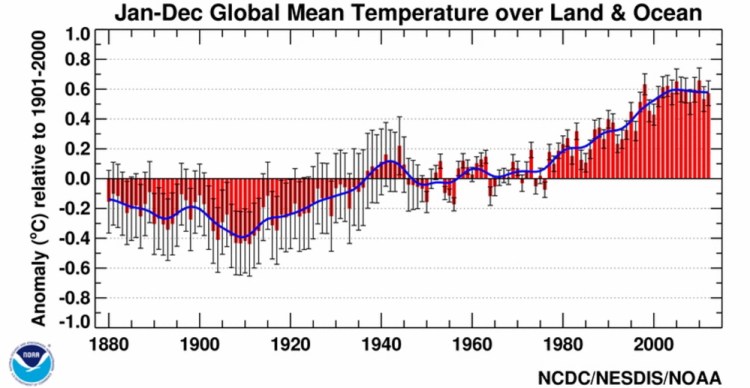

NOAA says the worldwide land surface temperature for June to August was 1.64 degrees above the 20th century average, the fifth-highest on record. The global ocean surface temperature was 1.13 degrees above the 20th century average, the highest on record for June to August; the previous record in 2009 was 1.06 degrees above the 20th century average.

A University of Hawaii study said this month that 2014 has seen the highest global mean sea surface temperatures ever recorded.

Even though it’s soothing to your conscience to think this is all a kind of random tumble of temperatures that the Earth experiences all the time, the fact is, it’s not. The general climate — and now the particular weather — is undergoing disruptions that are not business as usual over the past few hundred-thousand years, according to the climatologists. Measurements of our own hyped-up slashing and burning practices over the past roughly 200 years correspond directly to measurements of unsettling changes.

It’s not like no one saw it coming. In the 1700s there was a widespread perception that a general, unhealthy divorce of humans from nature was taking place. By the middle of the 1800s, coal smoke in cities was literally choking the life out of people.

A push for conservation had emerged in the U.S. by the late 1800s, partly because of incredible leaps in scientific understanding that helped lead to a new recognition of our situation in nature. In the humanities we call the American version of this recognition the philosophy of Transcendentalism. To say it more plainly, it was a re-invention of the way we look at the woods.

Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson and their friends realized that the idea of nature as a foe to be defeated was essentially a negation of ourselves — self-destructive, in other words. We are an element of nature. It informs us, and we inform it.

Thoreau, in particular, recognized that we live inescapably in a borderland between the necessities of civilization and the necessities of wild nature. Scientific method, for Thoreau, was a way of seeing into the layers of reality in our borderland.

“Let us not underrate the value of a fact,” he wrote; “it will one day flower in a truth.”

That is a key sentence. The physical world is a prism of truth and, moreover, beauty. It could be apprehended through scientific method, in Thoreau’s description, or as a personal experience, in Emerson’s description: “Standing on the bare ground … I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or parcel of God.”

Maybe, almost two centuries later, we would not express it quite this way. But on the other hand, many people feel a sort of reverence when we go to the woods to camp, fish, hunt or climb a mountain. We go there to put ourselves in the way of that feeling. It can get very strange, sometimes, when sunlight strikes a certain slant down through the trees, a blue jay whines in just the right crack of time, or the wind rattles oak leaves.

In that moment you feel like you’ve touched a spot of time where you and the naked beauty of nature are informing each other equally.

That can be a moment of transparent uplifting beauty, or it can be a moment of terror. A moment in which you remember, as I do, something like walking to work in a small city in the Balkans on cold winter mornings, with so much gauzy, sulfur-smelling coal smoke in the air that within 10 minutes you were short of breath. And realizing suddenly that this choking smoke has been pouring into the air worldwide for centuries from stoves, cars, factories, conflagrations.

The ancient Greeks’ story of Actaeon is one of those minor myths no one pays much attention to. He was a virile young guy who, like his friends, enjoyed hunting with his dogs and riding roughshod over the countryside. One day he paused to rest in some pine woods and heard a stream running nearby, and voices. He went nearer and saw, bathing naked in a clear pool, Artemis and her handmaidens.

There before him was the spirit of the woods in her pristine, naked, unforgiving beauty.

Artemis sensed him looking. Violated, she turned him into a deer. When he ran off, his own dogs hunted him down and tore him to pieces.

Before he saw nature in her true form, Actaeon lived in a sort of day to day, unthinking oblivion. When he stumbled upon nature unclothed, he was suddenly face to face also with his own violent violations of it.

It didn’t matter that he came upon Artemis naked by accident. The woods, as outdoorspeople persistently warn, do not care about you personally.

As science reveals layer after layer of reality, it also unfolds layer upon layer of beauty. Sometimes it’s a conventional kind of sensory beauty, like the Hubble photos from deep space; sometimes it’s an abstract kind of mathematical beauty, like the incredible finding that the amount of energy in a particle of matter is equal to the mass of the particle multiplied by the speed of light: e=mc2.

Sometimes we find layers that are not beautiful at all. Sometimes they’re terrible and horrifying.

Gee, we didn’t know we were poisoning the air, water and Earth. Or, even if we did, we didn’t mean to.

Doesn’t matter to Artemis. The warming oceans are already starting to dog us.

Dana Wilde lives in Troy. His writings on Maine’s natural world are collected in “The Other End of the Driveway,” available from online booksellers or by contacting the author at naturalist@dwildepress.net. Backyard Naturalist appears the second and fourth Thursdays each month.

Send questions/comments to the editors.