NEWTOWN, Conn. — Anxiety, depression, guilt, sleeplessness, marital strife, drug and alcohol abuse — two years after the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School, the scope of the psychological damage to children, parents and others is becoming clear, and the need for treatment is likely to persist a long time.

“Here it is two years later, and it’s still hard to deal with. But, God, you didn’t want to know me two years ago,” said Beth Hegarty, a Sandy Hook mother who happened to be inside the school that day with her three daughters, all of whom survived.

Hegarty and her girls are among the thousands of people in this close-knit town of 27,000 who have taken advantage of counseling and other programs made available through millions in grants and donations.

With the second anniversary of the shooting rampage approaching Sunday, agencies have been working to set up a support system for the next 12 to 15 years, as the youngest survivors approach adulthood.

Mental health officials say the demand for treatment is high, with many people reporting substance abuse, relationship troubles, disorganization, depression, overthinking or inability to sleep, all related to the Dec. 14, 2012, attack in which a young man killed 20 children and six educators before committing suicide.

And some of the problems are just now coming to the surface.

“We’ve found the issues are more complex in the second year,” said Joseph Erardi, Newtown’s school superintendent. “A lot of people were running on adrenaline the first year.”

The Hegarty children have had trouble sleeping and difficulty with loud noises and crowds. Whenever they leave the house, they look for places they can hide in case something bad happens. In February, a school counselor suggested the family seek help because one of the daughters wasn’t paying attention in class; she was staring at the doorway.

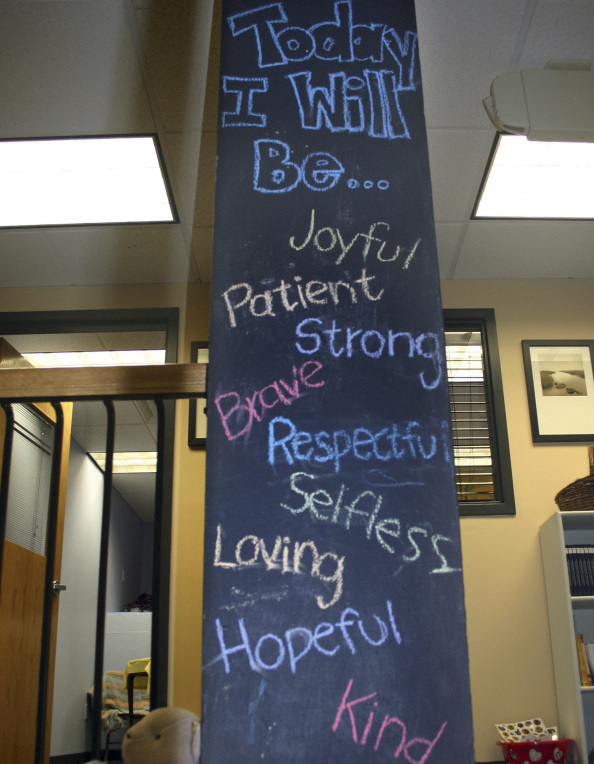

Hegarty and her children have been receiving support from Newtown’s Resiliency Center, an organization formed after the shooting that has seen rising demand for its offerings, which include art, music and play therapy. Hegarty said the programs have helped her become more “even-keeled.”

“I was super reactive to everything. I would fly off the handle on a whim. I was emotional. I couldn’t handle crowds or loud noises,” said Hegarty, who took cover under a conference table during the shooting while the principal and psychologist she had been meeting with died.

“For my girls, there is less running down the hallway in the middle of the night and climbing into my bed. They want to go more places instead of staying at home all the time.”

Newtown has received about $15 million in grants from the U.S. Education Department and the U.S. Justice Department to support its recovery.

The Newtown-Sandy Hook Community Foundation, which oversees the biggest pot of private donations made to Newtown, has about $4 million left after paying out more than $7 million to the families of the 26 victims and other children who were in the same classrooms but survived.

Newtown Youth and Family Services, the main mental health agency, has quadrupled its counseling staff, adding 29 positions in the months following the shootings, Executive Director Candice Bohr said. She said the federal grant money that recently came through will help cover its costs.

Jennifer Barahona, director of the foundation overseeing the private dollars, said the group has been spending about $60,000 a month on one-on-one counseling for people who have no insurance or whose insurers won’t cover such treatment. She said more people are reaching out for help every day.

The Newtown school system is starting a long-term program to teach young people from kindergarten through high school how to handle their feelings. It is also setting up a mental health center at the middle school in January to help those who were affected by the tragedy while in elementary school. Teachers have been trained to identify students who might have mental health problems.

Melissa Brymer, director of terrorism and disaster programs at the UCLA-Duke National Center for Child Traumatic Stress, has been consulting with Newtown to develop a plan to make sure the mental health needs are met for another 12 to 15 years.

Hegarty said she struggles with survivor guilt, but the Resiliency Center has helped her and her children.

“Are we 100 percent? No,” she said. “But will we ever be 100 percent? We might not be.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.