University of Maine senior Krystal Muggett is a full-time student working three jobs and worrying about the roughly $20,000 in student debt she’ll have when she graduates next year.

So it burns her up to see the school spending money renovating the student gym or paying for money-losing Division I sports teams when she’s going to classes in cold, drafty modular classrooms.

“You see the heavy focus on athletics here, and yet my classrooms are so old,” said Muggett, a social work major. “I see it and I question it.”

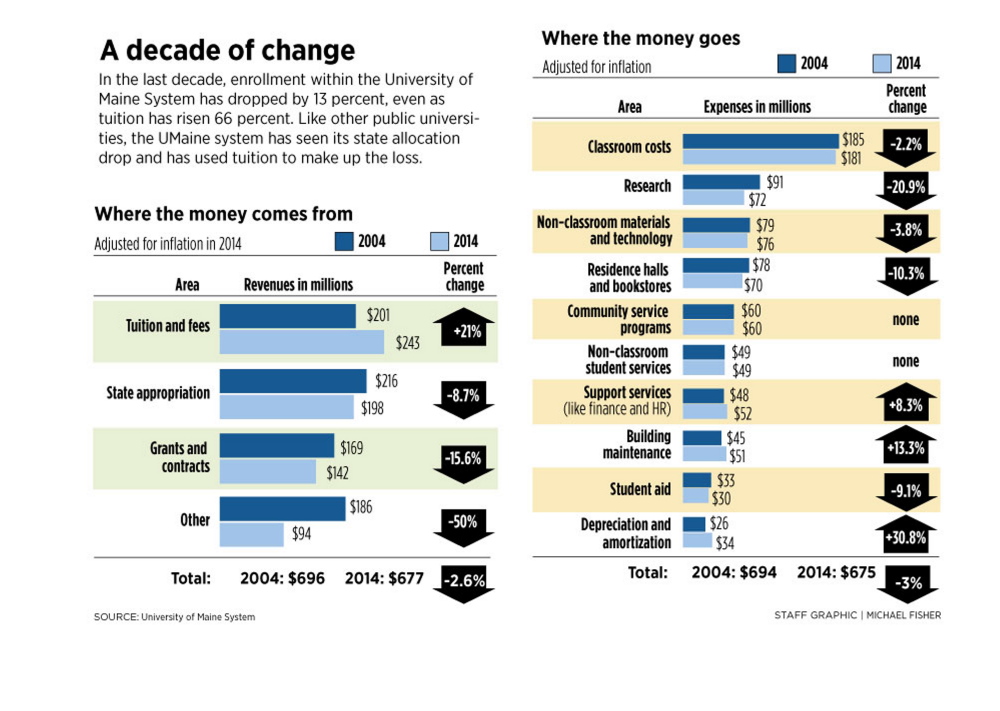

But while students and parents may think the steep rise in tuition is paying for fancy new facilities and high-priced administrators, that’s only a small part of the story. Public universities are spending slightly more money than they did 10 years ago on everything from upkeep of aging buildings to medical costs for employees, but the lion’s share of their tuition increases are plugging holes left by shrinking state funding.

Because of the recession, states slashed higher education per-student funding by an average 23 percent between 2008 and 2013, according to a report by the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. In Maine, the state allocation fell 15 percent over the same period.

In response, public universities increased tuition – their only other major source of funding – and made deep cuts in expenses.

The towers of Dickey Wood Hall on the University of Southern Maine’s Gorham campus are closed. Recent cuts at USM prompted protesters to sharply question the trustees’ and administration’s spending priorities.

“Essentially you’re paying more, but you’re not getting more,” said Donna Desrochers, one of the authors of the “Trends in College Spending” report by the Delta Cost Project and an education researcher at the American Institutes for Research.

And even when budgets are tight, schools still have to spend money to stay competitive, such as upgrading dorms, gyms and dining halls to attract and retain students.

Students and their families also expect more services from their colleges than they did 20 or 30 years ago, including mental health services, job training workshops, fiscal literacy seminars and free tutoring and academic help. All of that requires more employees to handle those jobs.

Nationwide, public universities have increased spending on those kinds of student services by about 15 percent in the past decade, more than twice the 6 percent increase in spending on instructional costs, according to the “Trends in College Spending” report. Overall, universities now spend about 27 percent of their budgets on actual classroom costs, including salaries for faculty.

TUITION’S STICKER SHOCK

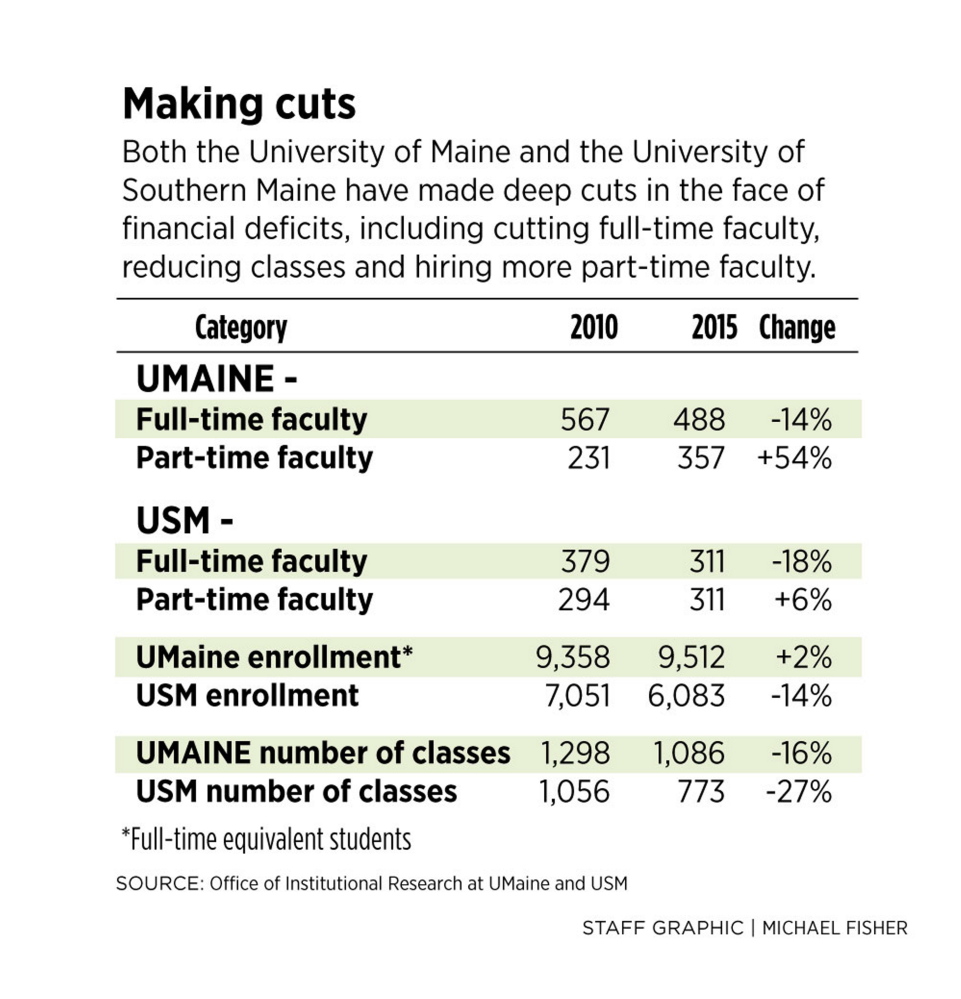

In the University of Maine System, spending for instruction has actually gone down by 2.2 percent, in inflation-adjusted dollars, since 2004, while spending on maintaining the buildings and facilities has increased 13 percent. Spending on student services has remained steady, although officials say those services have increased over time.

Private colleges also took a financial hit during the recession, and increased tuition. Their investments have largely rebounded, but private universities are still spending more on student services – up 24 percent in the last decade – than on instruction, up 11 percent during the same period.

The sticker shock of rising tuition has created a backlash, as more and more students graduate from college with historically high levels of student debt. In 2013, student loan debt held by 37 million Americans surpassed $1.2 trillion, exceeding all other forms of debt except mortgages. In 2012, seven of 10 bachelor’s degree graduates had taken out student loans, with an average debt of $29,400.

At the same time, tuition at public colleges has increased 40 percent since 2000, and spiked 231 percent over the last 30 years.

At the flagship University of Maine campus in Orono, in-state tuition and fees increased 66 percent in the last decade, from $6,394 in 2005 to $10,606 today – even with a tuition freeze instituted three years ago.

Colleges have responded to the financial pressures they’re under by making deep cuts. In other states, universities have closed entire campuses and scores of programs to deal with financial collapse.

In Maine, system officials have laid off hundreds of employees throughout the seven-campus system, at all levels. At the University of Southern Maine, which faced some of the deepest cuts, officials cut five academic programs and eliminated 50 faculty positions to close a budget gap, and will still need to borrow from reserves to balance the budget this year.

BIG TICKET TARGETS

Nationally, such cuts, combined with rising tuition, have spawned sharp critics who have their own ideas about where colleges should cut their budgets.

Athletics are a common target, because most sports programs lose money for their schools. Administrators say, however, that sports programs are critical to a campus’s culture, increase team-building and draw students who consider sports part of the college experience.

Ask someone else, and the big problem isn’t athletics, it’s overpaid administrators. Others say it’s overpaid professors who don’t teach enough. More recently, critics have blasted “luxury” student amenities, from dining halls that serve international cuisine, to gyms with Olympic-size lap pools and the latest equipment, to student dorms with walk-in kitchen pantries and free HBO.

Megan Ogden says she was attracted by the University of Maine’s recreation center. “I see the benefits of spending money on things like that,” said the studio arts major, who works out daily.

Even classes are under fire, with some critics wanting to strip down “nonessential” courses – ditching liberal arts subjects and beefing up on job-training programs and certifications.

But study after study has shown that those high-profile targets aren’t really to blame. It’s the loss of state subsidy that is behind the spike in tuition.

Overall, schools continue to spend most of their money on instruction, which includes faculty salaries and makes up about 27 percent of overall spending both nationwide and in Maine.

“Folks like to say, well, only 27 percent is spent on instruction. But when you look at what the dollars go into, the big bulk of where we spend our money is to support students whether it’s inside the classroom or outside the classroom,” said University of Maine System Chancellor James Page.

The system is also spending more on efforts to boost enrollment, including new senior administrators on campuses and high-tech tools to recruit prospective students.

All of it is very labor-intensive, said Rebecca Wyke, the system’s vice president of finance and administration.

“That is where your money goes. It goes to the people,” Wyke said.

MIDLEVEL STAFF

Among campus personnel, the number of midlevel professional staff – not professors, not top administrators – has seen the greatest growth nationwide, according to the Delta Cost Project.

Those positions grew twice as fast as executive and management positions at public colleges between 2000 and 2012, with the fastest growth in professional staff that provided noninstructional student support, according to the analysis released last year.

Critics also point to multimillion-dollar coaches’ salaries, top administrators with six-figure salaries, and costly athletics programs as wasteful spending on campus.

That’s less of an issue in Maine, where seven system employees earn more than $200,000 – six top administrators and the Orono Division I hockey coach. That is considered rich by Maine standards but well below national averages.

Recent cuts at the University of Southern Maine prompted some protesters to sharply question the trustees’ and administration’s spending priorities.

After the administration announced plans to cut 50 faculty positions and eliminate five academic programs, the Faculty Senate suggested that USM should at least explore whether to close one of the school’s three campuses instead of firing tenured faculty, a suggestion quickly shot down by the president.

STUDENT SERVICES

Student services have seen some of the greatest growth on campuses nationwide in recent decades.

Where once there was a single academic adviser in one’s major and some basic health and financial aid help, there are now subcategories of professional staff in a range of noninstructional student services, including financial literacy classes, career training, counseling, student wellness and internship opportunities.

“The rise in the cost of student services, I would argue, is the right expense,” Page said, highlighting one program that specifically helps first-generation college students succeed through tutoring or counseling.

That network of services increases the likelihood that a student will stay in school – and succeed – with the right support, according to Page and other college officials.

“I hear it all the time, that ‘Before I found the commuter lounge, I didn’t know where to go,’ ” said Barbara Smith, who runs the commuter and nontraditional student program at Orono.

What 10 years ago was an informal cluster of sofas in a corner is now a fully serviced lounge, with business-sponsored bagel breakfasts and work-study students staffing a desk to help students with questions. They have their own graduation breakfast, and special awards, and Smith seems to know the story of everyone in the room. Altogether, the program costs about $100,000 a year to run, officials say.

Beefing up the lounge may cost the university money, but it pays off in student satisfaction and retention, Smith said.

“I think students of whatever age need to really connect to an institution or they’re not going to stay,” she said.

The veterans services program, which helps answer vets’ questions and provides a staffed veterans lounge on campus, didn’t exist even five years ago, said UMaine Dean of Students Robert Dana, who is also vice president for student life. It also costs about $100,000 a year to run, he said.

The budget for all the student life programs, aside from dorms and self-sustaining services, is about $3 million a year, a fraction of the school’s annual $242 million budget. Systemwide, overall spending on student services is $49 million, out of a $675 million budget.

“It’s money well spent,” said Dana, noting that there are about 7,000 commuter or nontraditional students, and about 400 veterans and dependents on the Orono campus. “You can’t just not attend to that part of the population.”

NEW FACILITIES

Keeping a robust campus community, and investing in new dorms, performance halls and gyms, can play a big role in attracting students, top faculty and administrators.

That was the case for Megan Ogden, an out-of-state studio arts major at the University of Maine. When she toured the campus, she saw that her classes would be held in the 5-year-old, $10 million Wyeth Family Studio Art Center, and she could have daily access to a $25 million New Balance Student Recreation Center.

“I see the benefits of spending money on things like that,” said Ogden, who works out daily and was looking for a top studio arts programs. “It was pretty much the reason I enrolled in the program. I saw the facility and the student work and I figured they must have some pretty good instructors.”

The Wyeth Center resulted from a renovation of a former student dining hall and was paid through state bonds, Maine Technology Institute grants and private gifts.

The rec center, financed by a $25 million bond, has a swim center with lap pool, a current pool, a 20-person hot tub and a co-ed sauna. The first floor is dominated by eight basketball courts, ringed by a 1/10th-mile running track on the second floor, overlooking the courts. Spread throughout the gym are 140 pieces of cardio equipment and weights, and more than a dozen rooms for squash, badminton or group exercise classes.

Down the street, the University of Maine’s New Balance Field House and Memorial Gym is undergoing a $15 million renovation, paid for in part by a $5 million donation from New Balance, the remainder through a bond issue, fundraising and student fees.

The $25 million New Balance Student Recreation Center at the University of Maine in Orono has, among other amenities, eight basketball courts and a second-story running track. Investing in such facilities can play a role in attracting students, top faculty and administrators.

A few years ago, Page noted, UMaine sent out a survey to all freshmen at the end of their first semester, asking what they liked about the campus.

“Their largest single response was the quality of the (New Balance) gymnasium,” he said. “That was a big deal for that group.”

But while some of the university system’s expenses can be sponsored, it’s hard to find donors for some of its less high-profile needs: heating plants, plumbing, new roofs on old buildings. Fundraising campaigns or large gifts tend to flow to high-profile or high-concept buildings or projects, like the New Balance Student Recreation Center, or the recent $5 million renovation of Orono’s planetarium that was 83 percent funded through gifts.

By comparison, Orono officials are using campus funds to pay for a $1.3 million renovation of the room where dishes are washed at the Wells Commons Conference Center, and the University of Maine at Farmington is using $1.5 million in campus funds for a geothermal well field, and $700,000 to replace a boiler.

Those are the kind of unseen but necessary expenses that students and parents don’t see when they are touring a campus.

Some colleges are taking advantage of low interest rates to finance major projects, even if they have a healthy endowment. Colby College in Waterville is issuing $100 million in bonds, despite its $750 million endowment, borrowing at 4.25 percent interest while the projected return on its endowment is 8 percent.

The University of Maine System is also planning to issue up to $61 million in bonds next month, with about $14 million going toward energy projects and the rest used to retire older debt at higher interest rates.

COST SHIFTING

Despite the improving economy, a survey of university leaders in the U.S. released last month found that most don’t think their schools are in better financial shape. Two-thirds of the provosts, the top academic officer at a college, said they agreed or strongly agreed that funds for new programs would have to come from a reallocation of existing funds, or cost-shifting, and not from new revenue, according to the survey by Inside Higher Ed, in conjunction with researchers from Gallup.

One in four provosts said they expect to reduce the number of academic programs at their schools by the end of the 2014-15 academic year, the survey found.

That comes even as the drop in state funding is starting to level off. But despite that, half the states still spend less on higher education than they did five years ago, according to the annual “Grapevine” report issued last month by a national association, the State Higher Education Executive Officers.

In Maine, funding has increased slightly, 0.8 percent, over the last five years, according to the report.

UMaine System officials say there is still intense financial pressure to increase revenue, either through higher state subsidies or by raising tuition.

Although it falls short of what university officials requested, Gov. Paul LePage’s recent budget proposal would increase funding for the university system by 3.6 percent over the two-year budget, to $182.6 million for the fiscal year ending in June 2017.

Send questions/comments to the editors.