WATERVILLE — When she was 15 and a sophomore in high school, Alaina Wolman found out she was pregnant. She’d been dating her boyfriend, Jared, for almost two years.

“We took a pregnancy test — I took a couple actually — and they were all positive and I just couldn’t believe it,” Alaina, now 30, said. Initially, the couple just told the news to Jared’s mother because they were nervous about how Alaina’s family might react. When she was about two months pregnant, Alaina told her own family.

When she was about five months pregnant, Alaina enrolled in the Teen Parent School Program to complete her junior and senior years of high school.

“Before I came to the school, I wasn’t educationally driven,” she said recently. “I always went, but I wasn’t invested. After I started attending classes here, I had more of a reason to do well in school, and I had high honors and graduated on time when I should have graduated.”

Today she is one of dozens of young mothers who have earned high school diplomas through the program at the Maine Children’s Home for Little Wanderers. The program — which is celebrating its 40th anniversary year — enrolls pregnant girls and teen fathers in high school classes and provides child care and parenting education.

Only 40 percent of teen mothers in the United States finish high school, according to The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, a nonprofit group.

The program at the Maine Children’s Home is one of only two programs in Maine that offer a high school environment specifically for teen parents. The Good Samaritan program in Bangor is the other.

As the program marks its 40th year, staffers are trying to connect with graduates of the program to find out where they are and how their lives have turned out. The group estimates that about 1,000 teen parents — mostly girls — have passed through its doors, and they follow how the graduates are doing, including whether they went to college or if their children have finished high school.

The challenges facing teen parents are many — including nutritional issues, lack of transportation, difficulty finding and affording day care and social stigma. While conditions have improved since the program’s beginnings, there is still much to be done, said Sharon Abrams, executive director of the Maine Children’s Home for Little Wanderers and a former teacher in the Teen Parent School Program.

The program began to form in 1973 with teachers and staff at Waterville Senior High School when several girls dropped out of school after getting pregnant, said Sanford Adams, who was the executive director of the Maine Children’s Home at the time.

“The staff were wondering if the agency couldn’t begin an alternative high school program for these girls, where the student population would be made up of young women like them with the same challenges, where they could get the credits they needed and graduate,” said Adams, who is retired and lives in Connecticut.

They also hoped to provide child care for young mothers while they went to school, one of the reasons many pregnant girls dropped out.

“It started very small, which was good because we were all new at it at the time,” Adams said. There were about eight or 10 students the first year and just one teacher, Abrams, who began at the program just six months into her teaching career and pregnant with her second child.

“It was an interesting time, and I really I loved it,” Abrams said.

In its early days, the program offered young women life skills such as nutrition and meal planning and child care. At first students stayed for up to one year, then the program expanded to two and now students can take classes for up to four years, including after their pregnancy.

The program eventually added a support group for young fathers, paid for with a grant.

When the program merged campuses with the Waterville High School alternative education program in 2002, it also began offering classes for teen fathers.

The merger of the two programs helped some young men to feel more comfortable in the program, which has historically been made up primarily of girls, Abrams said. The program still doesn’t get a lot of teen fathers. None are currently enrolled and only a handful have joined over the years.

The program had two young men graduate in 2013, its first male graduates.

The impact the program has made on the lives of many of those who have attended is easy to see.

That impact was huge for Wolman, who now works as an administrative assistant at the Maine Children’s Home.

Today, Alaina and Jared are married and have two sons, Alex, 14, and Andrew, 10, and live in Skowhegan. She says the most rewarding part of her job is being able to work with teens whose situation she can identify with.

“I love it. I never dread coming to work,” Wolman said. “Even though I’m technically a secretary, I feel like I do more than that because I understand them on a different level.”

FINDING SUPPORT

Most teen parents who come through the program today raise their children themselves, and the program offers child care at no cost to the students while they finish high school classes. The program works in collaboration with the Waterville Alternative School and is able to offer a broader choice of academic classes for students by working through the school district.

About 15 students enroll in the program each year, and an estimated 1,000 area students have passed through its doors over the years.

For many, child care has been and today continues to be one of the hardest aspects of teen parenting. Linette Gamache was one of the first students to attend the program, enrolling during the late 1970s.

Gamache, of Vassalboro, was 17 when she became pregnant. A student at Waterville High School, she had run away from home and shared an apartment with another girl while working at McDonald’s. She often got sick when she was pregnant and had to quit her job.

After graduating in 1977, she raised her daughter, Jocelyn, for 10 months before giving her up for adoption.

“I just didn’t have the family support and didn’t think I had such a great upbringing so I wasn’t confident I could give my child a healthy, stable environment,” said Gamache, who was raised with a half-brother by a single mother. “I struggled as a child being raised by a single mom, and I just had all kinds of fears and insecurities that I couldn’t do a good job.”

Today, Gamache has a college degree and had a long career in insurance before moving back to Maine and starting a salon. She is married, though not to her daughter’s father, and has a son who is a college student. She volunteers for the American Cancer Society making wigs for people who have lost their hair because of cancer treatments.

MAKING A LIVING

Both Gamache and Wolman said that social stigma was one of the hardest parts of their experience, and that the program at the Maine Children’s Home provided a safe, judgment-free environment.

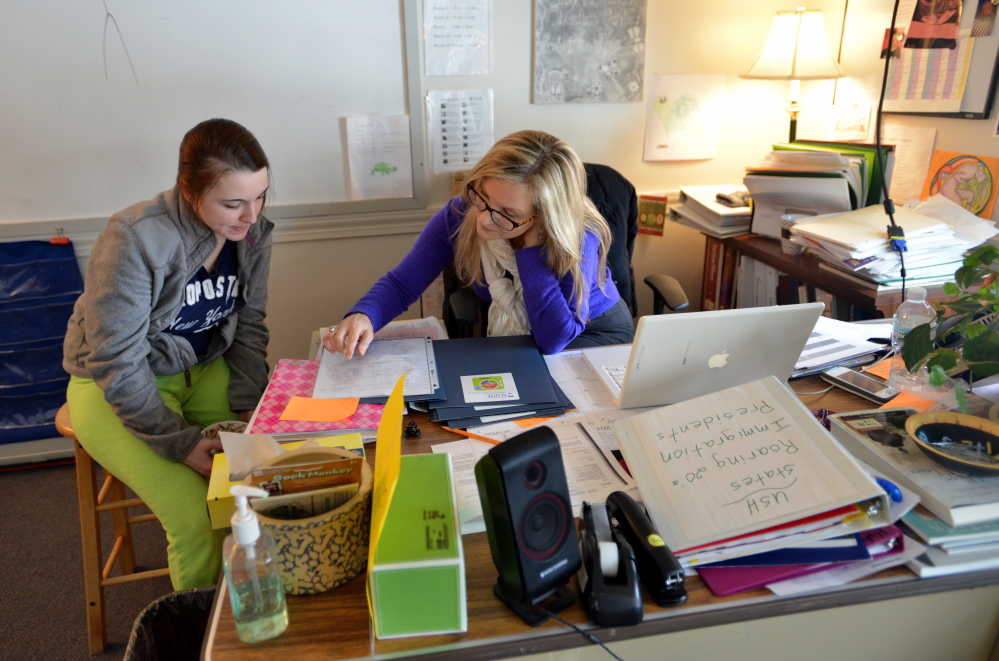

“Our students today still feel the judgment of being young and young mothers still in school,” said Angie Woodhead, the director of the program. “I think the one thing they really struggle with is when people say they’re babies having babies. I think they’re in a position where they’re pregnant and they’re trying to be the best parents they can be while finishing their diplomas. They work really hard to overcome lots of challenges, and they just want to be respected for that.”

Eight months into her pregnancy, 18-year-old Kayla Duguay of Augusta dropped out of high school.

“I was like ‘Screw it.’ People kept giving me dirty looks so I just went home and laid on my bed,” Duguay said.

She started classes at the Teen Parent School Program about a year ago after struggling to find a place to provide child care for her daughter.

She’s hoping to graduate in the spring and then take college classes at the University of Maine at Augusta or Kennebec Valley Community College. She said the program has helped her by providing diapers, food and clothes, as well as people she can talk to.

“Many of the challenges we are trying to eliminate through this program,” Abrams said. “For many of them, once they have a child, daycare and of course, transportation, are challenges.” Probably the biggest challenge facing pregnant teens and teen parents today is the lack of affordable housing available, she said.

“The economics of it is huge. They’re not always living with their family, and many of them are, by state standards, homeless,” Abrams said.

Duguay, who lives with her boyfriend, Ryan, said they struggle to make ends meet living off Ryan’s salary as a shift manager at Margaritas Mexican Restaurant.

“It’s tough,” she said.

Rachel Ohm — 612-2368

Twitter: @rachel_ohm

Send questions/comments to the editors.