I’ve always been uncomfortable with the idea of “outsider art” when that label is used to market a body of work, a book or an exhibition. The artist who epitomizes my discomfort is Henry Darger (1892-1973), a Chicago hospital custodian whose 15,000-page single-spaced manuscript and accompanying illustrations about the “child slave rebellion” tribulations of the “Vivian Girls” were discovered posthumously. To be sure, Darger’s work is epic to a rare degree. But my concern is the tone with which Darger’s story was colonized: Interest in Darger seemed more geared to being hip than developing understanding about the plight of emotionally challenged artists.

While the surrealists looked to outsider sources to take the viewer beyond his comfort zone, recent “outsider art” is more about bridging gaps in compassion, understanding and access. I have been impressed by this progressive and positive approach, and have seen more of it throughout Maine as well as the country. Two such exhibitions include Angel Braestrup’s sympathetic sculptural portraits of persons suffering from Alzheimer’s at Elizabeth Moss. At June Fitzpatrick, Lynda Litchfield’s paintings on clementine crates contemplate the idea that a lack of resources may lead to resourcefulness rather than the too-commonly presumed lack of sophisticated content.

ANGEL BRAESTRUP

I went back to clay sculptor Angel Braestrup’s exhibition “Mind Works” three times, in part because of the shifting modes of outsiderism in her work. Some of the work had a dissociative feel, while other modes seemed to buy into various densities of surrealism.

As it turns out, the three pieces that kept me going back are portraits of older folks suffering from degenerative cognitive illnesses. These three works still bother me and, in fairness, I can’t say if this is because of their content or because they are less compelling as sculptures. What is clear, however, is Braestrup’s compassion.

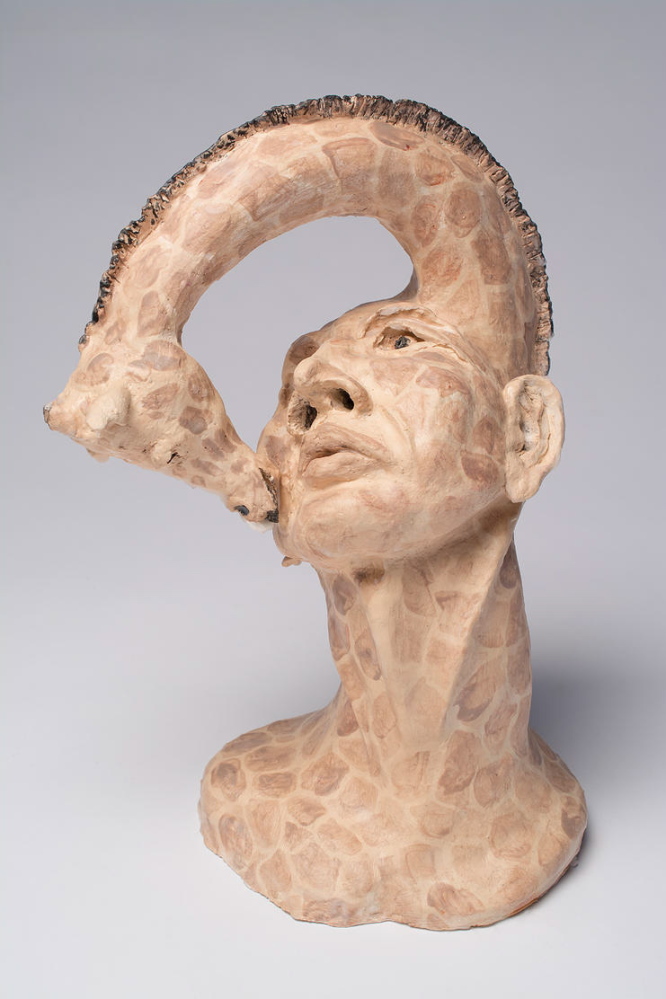

Braestrup’s other works range from playful fantasy to much heavier and darker archetypal observations. All of these flow with iconographic gates opened by the Surrealists, including twisted mythological symbols, psychological expressivity and fantastical dream-like transformations. A particularly strong work is “The Kiss.” It is a bust-style sculpture in which a giraffe’s neck grows out of a person’s head and bends around as though to kiss her/him, leaving only a tiny, electrified synapse between them. While the Dali-esque image remains psychically indeterminate, it is a superb sculptural form.

“The Reptilian Brain” similarly presents two figures that simultaneously are connected and dissociated. (The bifurcated brain structure does come into focus in “Mind Works.”) What is striking in this piece is that the two caryatid figures lean away from each other while being so elegantly bound to each other. It’s like a pair of mutually supported dancers, leaning out from each other, only we can’t see their joined hands; but it also features the ghostly lament of Auguste Rodin’s great “Burghers of Calais.”

After a while, it becomes clear that Braestrup isn’t relying on a specific iconography that denies understanding if you aren’t familiar with it. Realizing this makes the work much easier to enjoy.

Braestrup’s most ambitious work is a strange and fantastical chess set whose paper clay pieces incorporate animal hooves and tendons. (Paper clay is clay to which cellulose fibers have been added; this makes it lighter and weaker but hugely expands its structural and sculptural possibilities.)

Most striking are the bishops donning miters that are actual (disturbingly large) animal claws and the owl, donkey, lion, bull and sheep pawns with spring-like necks that are actually desiccated animal tendons. In the end, what is most uncanny about the set is that we can’t well enough distinguish the pieces to use them in a competitive game, and somehow that seems to be the point.

LYNDA LITCHFIELD

Lynda Litchfield’s abstract paintings made on wooden clementine crates are on the opposite side of the outsider spectrum. Instead of reaching out via metaphor, symbol and psychic observation, Litchfield’s works begin as loose paintings on very cheap found objects before turning inward on systems and painting logic to become extremely subtle and sophisticated works of contemporary art.

These works begin with “outsider” status the moment we recognize the cheap crates. While this seems quite a departure from Litchfield’s luscious encaustic work, we find in time that it is not. While the crates initially act to block the appearance of serious art, the works slowly and insistently reveal their painterly intellectual rigor while the viewer recognizes the artist’s forms and permutations as the snaking brush strokes and painted fields respond to the holes in the crates – and each other.

As their sophisticated formal project comes into view, we come to see the subtleties of the crates and how they are incorporated into the images. We see the orange interiors of the cheap, stapled crates at the triangle-supported corners, the ten-or-so punched holes and, most intriguingly, indirectly as reflected light on the wall. The reflected colored glow and shadow combination is a strategy I first saw used to such brilliant effect in the work of New York assemblage painter Cordy Ryman, but Litchfield’s approach is particularly fascinating by critically addressing the object-qualities of her encaustic paintings. (And her use of Flashe paint reminds me of the greatest transformation I have witnessed in Maine painting: Mark Wethli’s move from breathtakingly hyperrealist interiors to initially crude-seeming formalist abstraction.)

While Litchfield’s clementine crate paintings ultimately come into focus as supremely sophisticated, internally-driven systems paintings, they also achieve a bit of Herculean conceptualism by resurrecting the crates. In this case, the extraordinary transformation forces us to confront our own initial assumptions about “outsider” objects. It’s a subtle but impressively powerful kernel of socio-political content. (Yes, political: Recall Rahul Mitra’s community crate piece at the 2013 PMA Biennial.)

But that’s what outsider art is all about – perching on the very edge of our comfort zones. Once it’s fashionable, after all, it’s no longer outsider art.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.