Readers who enjoyed the first volume of John Moon’s “City by the Sea,” published in 2010, will find its sequel equally charming and a work that stands as its own unique picture history.

The author, a Portlander by birth and inclination, is a graduate of the University of Southern Maine and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and now a business consultant, researcher and photographer. He has created a specialty for himself, selecting superior early black-and-white images from local collecting institutes and matching them with his own contemporary shots.

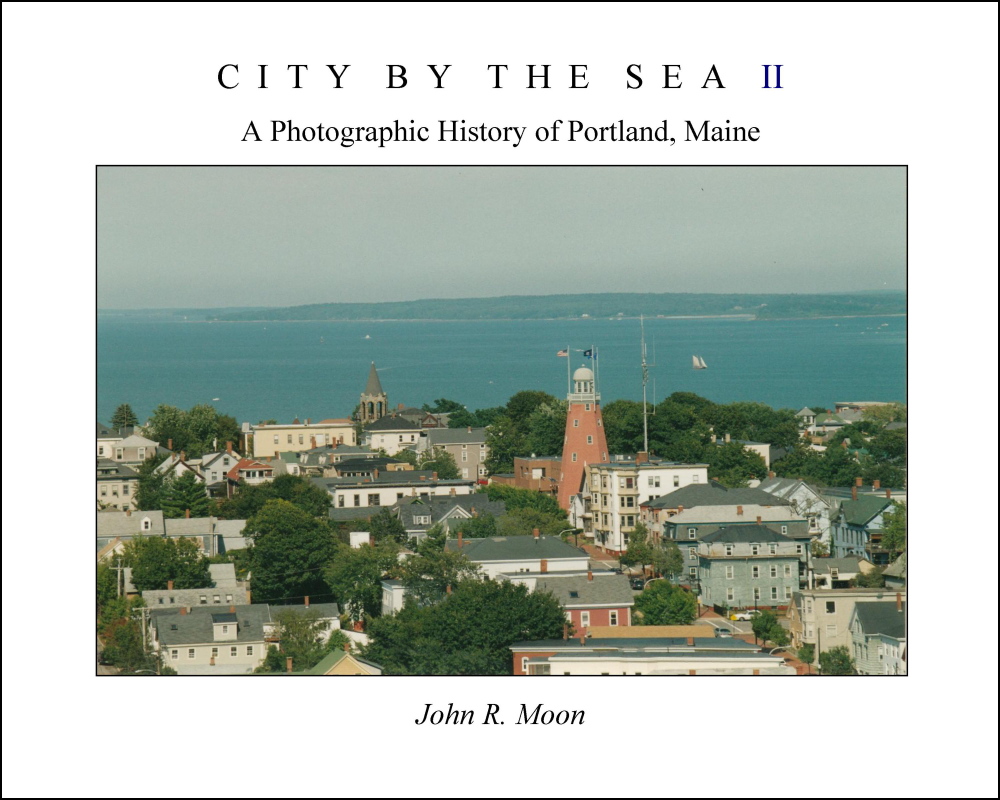

“City by the Sea II” is not just an album of more charming visions of the Forest City. The historic images are well chosen and in some cases previously unseen in printed form. There are no glamour shots that try to make the 1807 Portland Observatory look like something out of a glossy magazine. The cover photo shows the Munjoy Hill tower handsomely surrounded by triple-deckers and a sailboat plying Portland Harbor in the distance. If there is graffiti on the walls of some of Moon’s images, so be it. This is Portland at the outset of the 21st century.

Some scenes, including one of the State of Maine Armory (1895) designed by architect Frederick A. Thompson, have kept their integrity and usefulness. The armory is now a downtown hotel – the Regency – and Moon captures a dignified wedding party leaving the building, a very human record of our era depicting a sterling example of “creative reuse.”

His choice depicting the Mariner’s Church, built in 1829 on Fore Street, comes from the late 1960s, when it was nearly abandoned except for a coffeehouse on the third floor. While there are those among us, including yours truly, who can recall the sound of voices mixed with guitars and autoharps, the building today is bustling with eight small businesses.

The junction of Forest and Allen avenues was in 1912 the site of the four-story brick Morrill House Tavern, a stately structure shaded by elms. Built about 1805, the tavern was torn down in 1957 (not 1933, one of the book’s few minor errors). Moon’s present-day view of the site could be anywhere in the United States, a sun-blasted chunk of blacktop with a stoplight, convenience store and “one of the busiest and most dreaded intersections in the entire city.”

If you ever want to see history or, rather, the passing parade in building form, take a gander at the magnificent view on page 66 of the Portland Automobile Sales Company (formerly the Portland & Yarmouth Electric Street Railway Garage) from the 1930s. Today, only a nub remains, but the photographer catches it in all its tagged humiliation.

Preservationists regularly bemoan the loss of Portland’s Union Station, and the author-photographer comes through with old and new photos. But it is the eastern rail gate, the Grand Trunk Station, that really stuns the viewer. Moon writes, “It is incredible to see this corner today and think of it as a better use of the property than when the Grand Trunk Station was there.” The concerned Portlander should consider the bright and changing shape of the city, especially around India Street and Munjoy Hill today.

While the author does comment on the images, they really stand on their own to document Portland and capture a frozen moment – an automobile, a gasoline pump long gone, vessels in the harbor, parks and green spaces, without or with trees. Consider the old Portland Yacht Club, designed by John Calvin Stevens in 1927 at the end of Central Wharf. It is one thing to explain the club is now located in Falmouth and to state the former approximate location. It is another to see the Portland location today from a boat in the Fore River.

William David Barry is a local historian who has authored/co-authored seven books, including “Maine: The Wilder Side of New England” and “Deering: A Social and Architectural History.” He lives in Portland with his wife, Debra, and their cat, Nadine.

Send questions/comments to the editors.