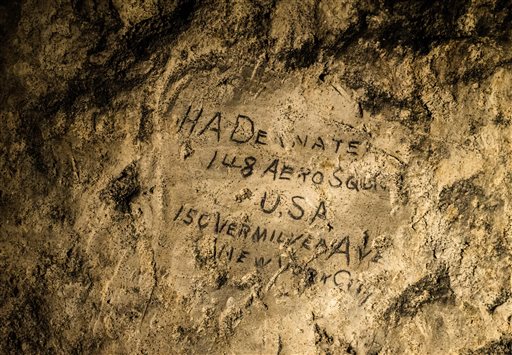

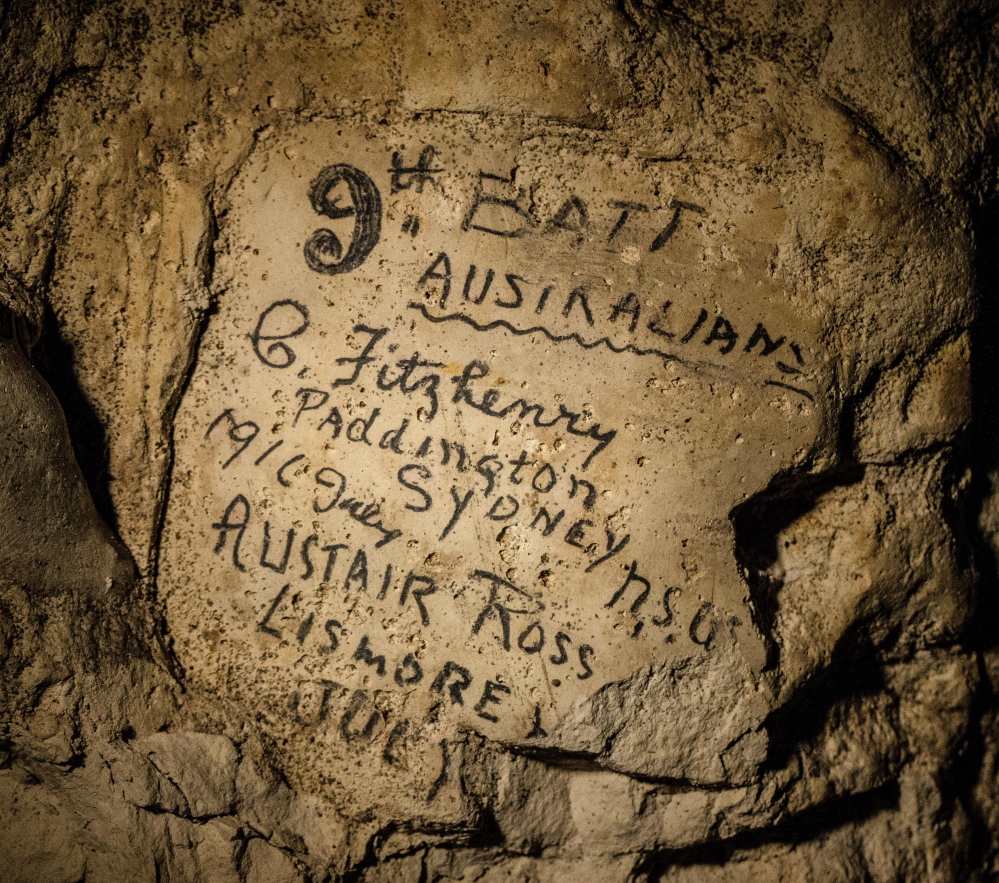

NAOURS, France — A headlamp cuts through the darkness of a rough-hewn passage 100 feet underground to reveal an inscription: “James Cockburn 8th Durham L.I.”

It’s cut so clean it could have been left yesterday. Only the date next to it – April 1, 1917 – roots it to World War I.

The piece of graffiti by a soldier in a British infantry unit is just one of nearly 2,000 century-old inscriptions that have recently come to light in Naours, a two-hour drive north of Paris. Many marked a note for posterity in the face of the doom that trench warfare a few dozen miles away would bring to many.

“It shows how soldiers form a sense of place and an understanding of their role in a harsh and hostile environment,” said historian Ross Wilson of Chichester University in Britain.

Etchings, even scratched bas-reliefs, were left by many soldiers during the war. But those in Naours are “one of the highest concentrations of inscriptions on the Western Front” that stretches from Switzerland to the North Sea, said Wilson.

The site’s proximity to the Somme battlefields, where more than a million men were killed or wounded, adds to the discovery’s importance. “It provides insight into how they found a sense of meaning in the conflict,” said Wilson.

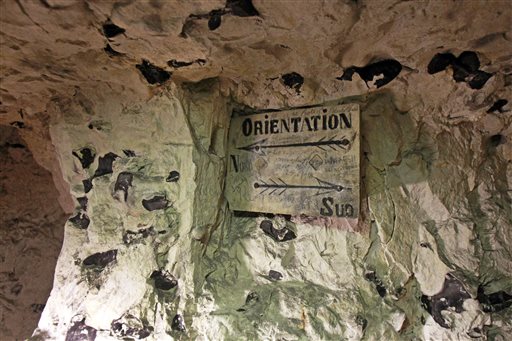

Naours’ underground city is a 2-mile complex of tunnels with hundreds of chambers dug out over centuries. During the Middle Ages villagers took shelter there from marauding armies crossing northern France. By the 18th century the quarry’s entrance was blocked off and forgotten.

Send questions/comments to the editors.