When Misty McLaughlin and her husband moved to Maine from Texas seven years ago, she didn’t need to think about finding a job.

She brought it with her.

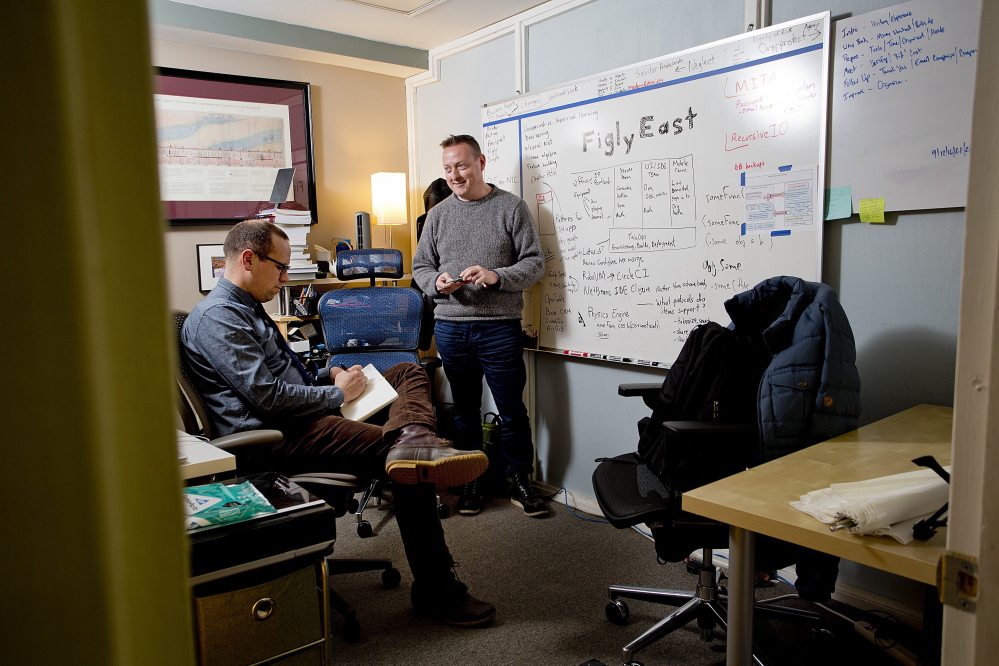

The same was true for Elliot Murphy, a software engineer who figured he could live pretty much anywhere he could find a high-speed Internet connection. Maine seemed like a good option, so he picked up his high-tech job and moved to Portland from Florida three years ago.

The two are examples of “remote workers,” a growing slice of the state’s workforce being studied by the Maine Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Southern Maine.

McLaughlin, a consultant for a Washington, D.C.-based software company, and Murphy are among those workers who can live where they choose and largely ignore the idea of having to move somewhere for a job.

“We’re not here because we’re transplants or itinerant,” McLaughlin said. “We want to live here and build a life here.”

Ryan Wallace, the center’s project director, said he’d like to get a handle on the number of and growth in remote workers because he believes they could represent a significant shift in the labor force, as well as an opportunity for the state’s economy. Many of them come from high-tech industries and earn paychecks in line with those in Silicon Valley and Seattle. The benefit could be significant for Maine, where young, well-educated people are needed to stem an aging workforce and help increase below-average wages.

“It’s really tricky to pinpoint a number on these folks,” Wallace said, “(but) it’s a really big story, I think.”

DATA ON WORKFORCE HARD TO COME BY

The MCBER says that 5.3 percent of Maine’s workers work from home, about 1 percentage point higher than the national average. That compares with the 4.3 percent of workers who were home-based in 2000. But about half of those people are self-employed, workers who are not, by definition, working remotely for someone else.

The numbers are hard to come by because the IRS doesn’t track where a company’s workers are based, Wallace said. Companies are only required to file payroll data from their home office.

Likewise, Census numbers track how many people work from home, but not whether they are working for a company based elsewhere.

The phenomenon has developed only in the last generation, with the advent of Internet connections, email and cellphones. Before that, working from home for anyone other than the self-employed was fraught with difficulties.

And, while technology has made it easier to communicate with co-workers and customers hundreds or thousands of miles away, hurdles remain.

For instance, McLaughlin said making sure everyone is working with compatible software is important, as is picking an Internet provider that provides high-speed, reliable service.

“This is new,” she said, “this is not stuff previous generations dealt with.”

But the advantages outweigh the disadvantages, she said, particularly the ability to get back to work after she had a baby, because it meant continuing to work from home.

Jason Fried, the co-author of “Remote: Office Not Required,” said the ability to balance work/life priorities while maintaining a career is just one reason why off-site work is gaining favor nationally.

Fried, who runs the software company that developed the project management software called Basecamp, said he’s based in Chicago, but 35 of his 48 workers are in 30 different cities.

Setting up a company where remote working is a founding principle makes finding talented employees easier, he said.

“It’s unlikely you’ll find the right person for the job within a 30-mile radius of where your office happens to be,” he said.

‘WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR THE FUTURE?’

USM’s Wallace said his center plans to try to pull together numbers that may make it easier for Maine to adopt policies that recognize the impact of remote workers and promote it. As the state’s workforce ages and contracts, promoting the state as a place where remote workers are welcome could help offset some of the job losses in traditional industries that require a worker to show up at an office or factory every day.

“Policymakers need numbers – how do you quantify things, quantify impacts?” Wallace said. “But there’s clearly something going on and clearly broader shifts. What does it mean for the future? Do these trends really completely transform the way we do work?”

McLaughlin said she’s looking for answers to similar questions and is working with groups such as Creative Portland to a hold a national summit in Maine next year to examine the phenomenon and discuss its impact.

It’s tentatively called the “Work in Place Summit,” which she said will examine “the new geography of work.”

“It’s a great way to bring high-commitment, high-revenue people to the state in a way to enhance what we have in a sense of place, as opposed to extract or detract from it,” she said.

Murphy recommends it. Working remotely means people find that they can do things like pick their children up from school and prepare a home-cooked meal while still putting in a full day’s work, without commutes that can easily eat up two or three hours of the day.

“The idea that the company office is this quiet sanctuary isn’t true,” he said. “Unless you are in a customer-service job that requires face-to-face contact or a factory job or a restaurant, pretty much every job can be done remotely. The technology that exists makes it easy today.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.