MACHIAS — When Kat Ragot, 42, accepts her diploma for a bachelor of arts degree Saturday from the University of Maine at Machias, she will finish a journey that began 25 years ago and left her nearly $40,000 in debt.

While fellow classmates who graduated from her first college, Carnegie Mellon University, went on to enjoy successful careers, Ragot dropped out, then struggled to make ends meet while working a series of low-paying jobs and raising two children on her own. She defaulted on her student loans, but later restored her credit so she could borrow more money and return to school.

She needs that college degree, she says, so she can get a better-paying job and climb out of the financial hole she has fallen into.

“There’s no way around it,” she says of her lingering debt. “It’s kind of like a mortgage. The payoff will ultimately be more security – and that’s a debt worth taking on.”

Today more than ever, a college degree is a pathway to the middle class. But failing to stay on that path can be devastating to students like Ragot, who drop out or take years to finish. They are more likely to struggle financially through life and default on their college loans.

A lot of people in Maine have started on the path to a college diploma and have fallen off.

Between 180,000 and 230,000 Mainers have attended college but never received a degree, according to a 2014 report by Educate Maine, a business-led education advocacy group. For Mainers age 25 and older, one in five have had some college education but no degree, a rate slightly higher than the average in the Northeast, according to 2013 estimates by the U.S. Census.

While there are no data available on the size of the debt burden carried by Mainers who never finish college, the vast majority of students who default on their student loans never finished college, according to data tracked by the Finance Authority of Maine.

Those who default on student loans are prohibited from discharging the debt through bankruptcy. The federal government can work through a collection agency to garnish wages, income tax refunds and Social Security benefits.

The financial consequences of default are long-lasting, says John Dorrer, a workforce development expert and former chief economist and research director of the Maine Department of Labor.

“You can’t shake that off,” he says. “It follows you through life.”

DEFAULTERS IN A CATCH-22

There aren’t many stranded learners from Maine’s elite private colleges like Bowdoin and Bates, which select students from a large pool of applications and weed out those who are at risk of dropping out early. At Bowdoin College, for example, of the 147 students who began repaying their student loans in fiscal year 2011, only one student defaulted on federally subsidized student loans over the ensuing three years, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

At Southern Maine Community College, 322 of the 1,575 students who began making payments that year defaulted – a rate of more than 20 percent. Washington County Community College had a default rate of nearly 30 percent.

The national average for the same time period is 13.7 percent. In Maine, 2,300 of the 18,000 borrowers who began making repayments in 2011 defaulted within three years – a rate of 12.8 percent. These default rates don’t include students who default after three years or who default on private loans.

Between 70 percent and 90 percent of Maine residents who default on federal student loans every year have never finished college, according to Mary Dyer, a financial education officer at the Finance Authority of Maine. This performance is consistent with data tracked by states across the country, Dyer said.

The defaulters typically owe a relatively modest amount, $9,500 to $14,000, but aren’t able to pay off the loan because they lack the diploma or certificate that gives them access to a decent-paying job, she says. With bad credit, they can’t borrow money and return to college and finish the degree, so they become trapped in low-paying jobs with no way out.

“They are in a Catch-22,” she says. “They can’t get financial aid to pay for school, but to complete a degree they need financial aid.”

Borrowers default on loans if they don’t make on-time repayment in nine consecutive months or if they fail to make some kind of arrangement with the loan servicer, such as creating a new payment plan based on their income. The federal government estimates that 18.4 percent of students who began making their loan payments in 2011 will default within 20 years.

WORTH THE COST

While Maine’s high school graduation rate is higher than most states, Maine trails the nation in the percentage of students who enroll in college; it does slightly better in the percentage who stay there.

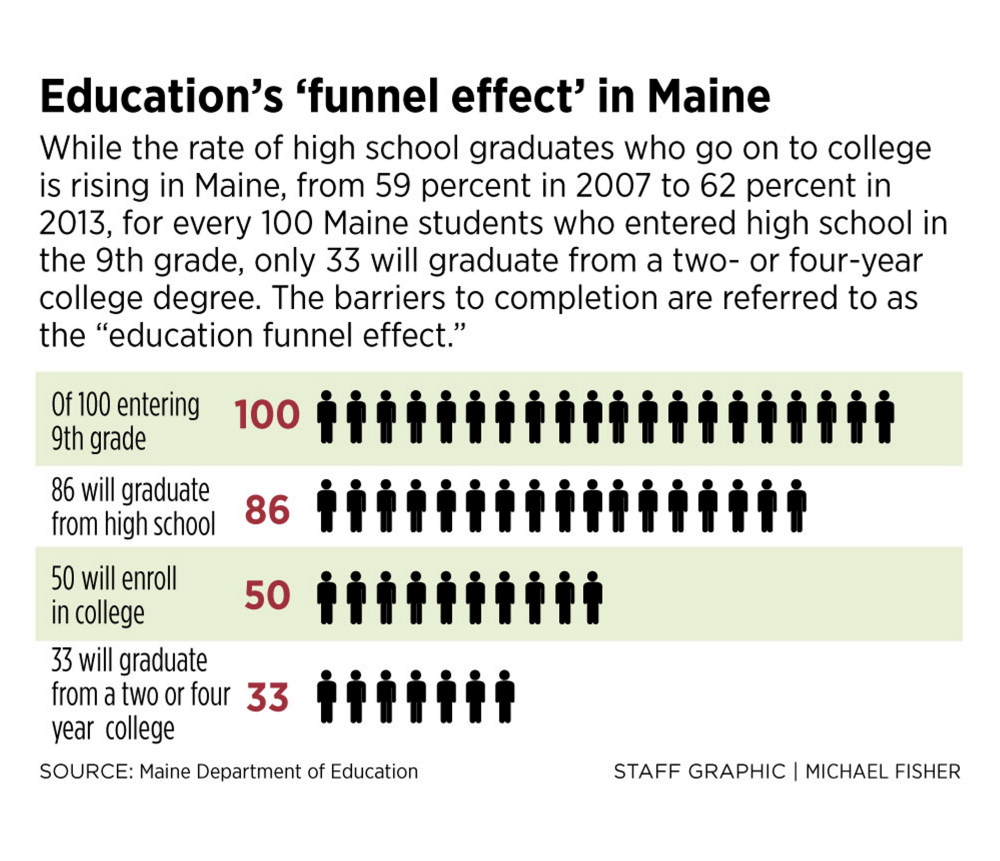

For every 100 Maine students entering ninth grade, 86 will graduate from high school and 50 will enroll in college within a year. But only 33 will graduate from a two-year or four-year college, according to the 2014 National Clearinghouse Student Tracker report for Maine and the Maine Department of Education.

Nationally, for every 100 students entering ninth grade, 75 will graduate from high school and 51 will enroll in college within a year. Only 29 will graduate from college.

Most of the dropouts leave after their freshman year before they rack up too much debt, but the more tragic cases are those who leave in their junior or senior years, says Rosa Redonnett, chief student affairs officer at the University of Maine System. Those students leave heavily in debt, but all the classes they’ve already taken don’t count for much in the workplace.

“It’s a stranded investment,” she said. “You made this big investment, and it doesn’t result in anything other than debt.”

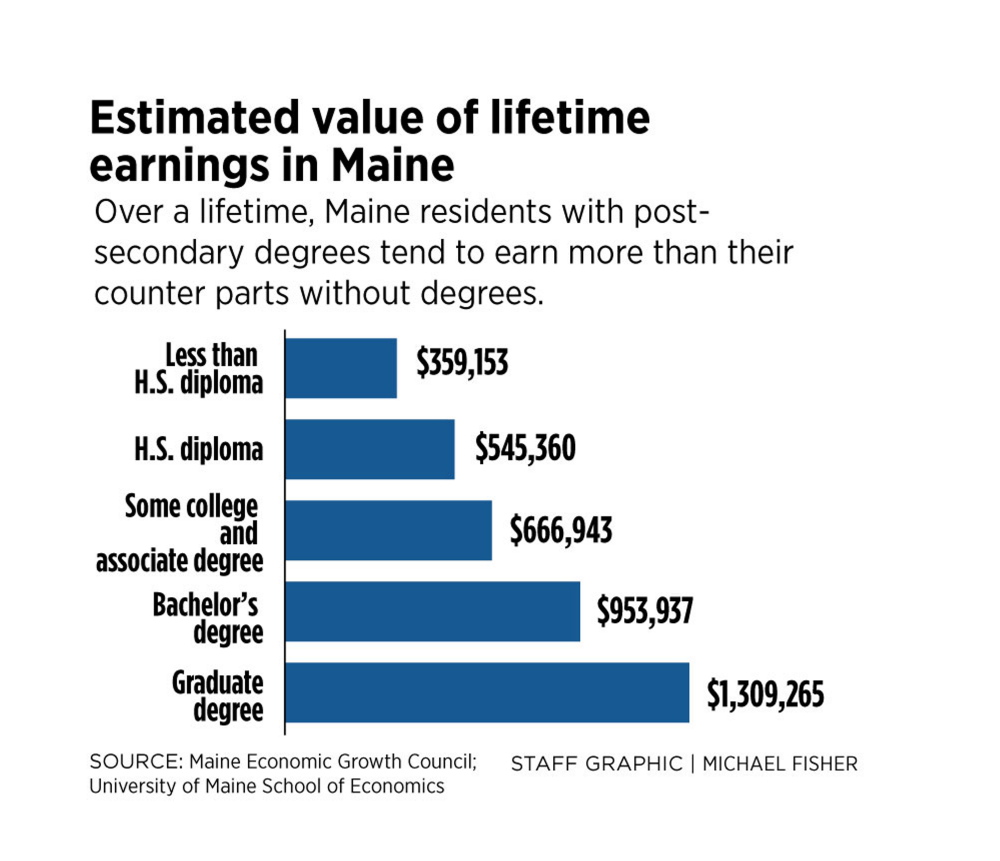

Despite sharp increases in tuition at higher education institutions nationally in recent years, a college degree is generally worth the cost – about $1 million more in additional income over a lifetime, according to numerous national studies, including a 2014 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

College graduates are more likely to be employed than those with a high school diploma or some college. The unemployment rate in March for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher was just 2.5 percent, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The unemployment rate for those with some college or an associate degree was 4.8 percent, and for high school graduates it was 5.3 percent.

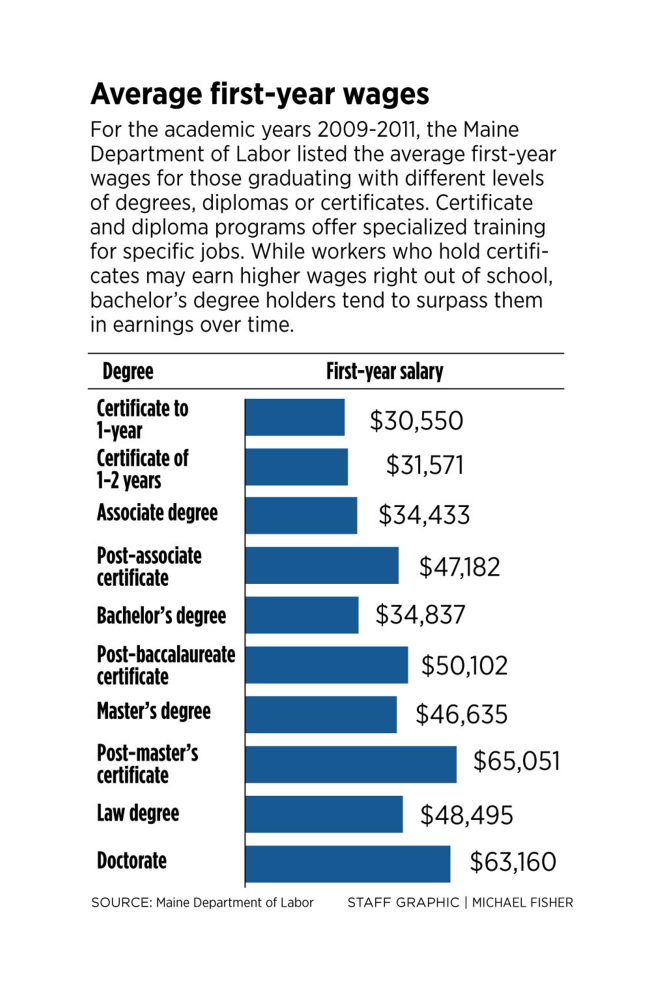

Although a college degree is worth the money, not all types are an equally good investment. While the specific college a student attends matters, to some extent what really counts in earning power is what he studies, says Anthony Carnevale, an economist who is director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. The financial payoff is significantly greater for those who major in engineering or computers rather than the humanities.

For students studying social sciences, physical sciences and biology, getting a master’s degree boosts their income because jobs for candidates who hold just a bachelor’s degree tend to be scarce. A few majors, like psychology, aren’t worth more than a high school diploma unless students also go on to a master’s degree, Carnevale says.

FOR POOR, HIGHEST RISK

There is one group, Carnevale says, for whom not finishing college turns out to be a terrible investment: working-class students who drop out and default on their loans. With ruined credit, they will almost never get another loan and the financial setback is so great they may never recover.

“The big losers in the game are the non-completers,” he says. “The rich kids can make a lot of mistakes. For the poor kid, that’s it. If you screw up, you’re done.”

The dropout problem is greatest among the nation’s community colleges. Nationally, just 35 percent of full-time community college students seeking a degree graduate within five years. By then another 45 percent have “given up completely” and are no longer enrolled, according to a report released in February by MDRC, a nonpartisan education and social policy research organization based in New York City and Oakland, California.

Unlike selective private colleges and public universities, community colleges can’t exclude students who are poorly prepared. In addition, despite the relatively low tuition cost of most community colleges, poor students still struggle to pay tuition bills, and cope by working more hours or attending school part time, both of which lead to reduced academic success, according to the MDRC report.

Many students are the first in their families to attend college and are less likely to understand how to navigate college, the report says.

That was the situation with Spencer Hardy, 20, of Parsonsfield, who earned his high school diploma after passing a GED test and enrolled in Central Maine Community College in Auburn to study culinary arts and business. After a year and a half of schooling, he stopped attending classes but still lived in the dorm. He now owes about $12,000 in student loans. He would like to return to college, but says he can’t until he pays the college back the $2,700 he still owes. The college also won’t give him his transcript until he pays the money.

The chances he’ll default on his loan seem high. With no job, Hardy is so strapped for cash that the water company recently shut off the service in his apartment for lack of payment.

His mother, Kristin Hardy, who never attended college herself and cleans houses for a living, says she’s frustrated her son didn’t get more guidance in college and that the system seems rigged against poor families. Still, her son is ultimately responsible for what’s happened, she says. “I tell him it’s a trap he put himself in.”

For Laura Applin, 24, who works as a waitress at Becky’s Diner in Portland, leaving college made sense because she couldn’t justify paying huge tuition bills when she lacked direction.

“I didn’t know what I wanted to do,” she said. “I felt I was wasting all my money on school.”

Applin attended Simmons College in Boston for a year and then transferred to the University of Southern Maine, where she was a part-time student for less than a year. Her college loan debt, originally $26,000, is now down to $17,000. She plans to return to college and study business because she wants to open her own specialty grocery store someday.

Older students who return to college, however, often face obstacles because their lives become more complicated. They have bills to pay, like car payments, and often children to support and care for.

Ragot, of Cutler, began taking classes at the University of Maine at Machias in the late 1990s. She dropped out, though, needing to earn only 18 more credits for a bachelor’s degree. She was barely getting by financially and had to get a job to pay the bills. Moreover, her two young boys were both sick at the same time and needed her attention.

“It was brutal,” she says of that time in her life. “Being a poor, single mom in Maine is an insecure situation no matter how much education you have. There are so many barriers.”

COLLEGES OFFERING MORE GUIDANCE

Some students drop out because they’re not prepared academically, says Glenn Cummings, acting president of the University of Maine at Augusta, a commuter school that mostly serves adults who have jobs and families. Those students, who must take remedial courses, start college at a disadvantage because the remedial classes cost money but aren’t counted as college credits, he says. Other students do well academically but are so “financially fragile” that an unexpected event, such as losing hours at a part-time job or costly car repairs, causes them to drop out because they can’t make the tuition payments anymore.

Cummings tells students that the financial cost of quitting is so high that they must be prepared to finish college once they start.

“Higher education is like walking a tightrope between two skyscrapers,” Cummings said. “You have to keep walking. You have to put one foot in front of the other. You have to keep making progress.”

Only 26 percent of the university’s students, including those who begin as part-time students, graduate within six years. This year, the university began offering $1,000 “Fresh Start” scholarships to give students who owe a previous balance an opportunity to return to UMA.

The University of Maine System last year began offering as much as $4,000 per year in scholarships to adult students returning to school after an absence of three years or more. The $1 million scholarship program is primarily intended to encourage students who already have earned a significant number of credits to complete their degrees quickly.

In addition, the system has established a “concierge” service at each campus, modeled after the hospitality industry, to guide students through the education process, such as choosing a major and finding financial assistance.

Financial aid staffers at each school are also helping defaulters restore their credit, a long and complicated process that requires students to get back into good standing with the agency that services the loan.

Despite all the data showing that college graduates earn more money, it’s still more difficult for adults to return to school. Their lives are more complicated when they get older, and they need a lot of individual guidance to figure out ways around potential obstacles, such as paying for college and arranging for child care, Redonnett says.

“It’s still a rough road for people to come back,” she said.

The community college and university systems also are working to prevent people from dropping out in the first place.

Cummings says research shows that students respond well when they have strong personal connections with adults at the college, such as a faculty member or adviser. The college is now hiring its first “success coach” to give students individual attention. The program is modeled after the “Path to Graduation” program established last year by Southern Maine Community College.

The KeyBank of Maine Foundation is giving $500,000 to SMCC to hire two full-time advisers to assist 90 students in the first year and 150 students in following years. Although the college’s enrollment has been growing over the last decade, only 14 percent of SMCC students graduate within three years, with another 18 percent of students transferring out to another college.

Ryan Donkin, a first-year student from Naples, says he got poor grades in school because he focused on having fun rather than studying. When he first started at SMCC, the workload was overwhelming.

“I really had no plan for success. I didn’t know what I was doing. I didn’t know why I was there,” he said.

He now meets with his success coach, Kristi Kaeppel, once or twice a week and communicates with her by email about five times a week. He says Kaeppel helps him plan his time, stay organized and figure out what courses to take.

“You have a feeling that you are not alone,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.