READFIELD — The stories of war are most often told in broad strokes. There were the 5,000 who died there, on that date, in an unfamiliar land, a long time ago. The magnitude of the numbers have an anesthetic effect, taking away the pain those who hear it can only imagine others must feel.

But the story of one soldier, and the relationship students at Maranacook Community High School have built with his surviving brother, has allowed the students to look beyond the numbers at the pain and loss up close.

“I feel like we forget that these people involved in these wars had lives before they went to war,” said senior Natalie Wicks, of Readfield. “It’s just a mass of people that we think of, but everyone had their own story. They weren’t just another number in an Army.”

Finding those stories and telling them are at the heart of Sacrifice for Freedom, an elective class that combines history and foreign language. The class, seniors and one junior, is working on an array of projects, including German prisoners of war, some of whom were held in Houlton, and the French Resistance of World War II.

“These students have been exercising real world, historical research related skills to keep alive the stories of the sacrifices made during the war years,” said history teacher Shane Gower, who instructs the class with French teacher John Hirsch.

One of those stories belongs to Lewis Frelan Goddard, and the students have heard it from one of the people who loved him best, his brother, Robert Goddard of Richmond.

Robert Goddard was 10 when Lewis was a member of the elite Jedburgh operation in World War II, teams trained to parachute behind German lines and work with the French Resistance. The effort included conducting clandestine operations to assist the advancing Allied forces.

Lewis Goddard, who grew up in Knoxville, Tenn., trained for months, but never got to carry out his mission.

He was killed Aug. 7, 1944, when his parachute became entangled in equipment sent out of the plane just before him. Goddard, who was 20, fell to his death in Beddes, France, where the villagers hid his body from the Germans until they could bury him with a proper ceremony.

Goddard’s body was later exhumed and interred at the U.S. Military Cemetery in Draguignan, France, with about 800 soldiers killed in action.

The Maranacook students on Wednesday will unveil a memorial on school property to honor Goddard.

“Having his brother tell us the story meant a lot more than just reading about it,” said Johan Nel, of Wayne.

UNUSUAL INTEGRITY

Robert Goddard, now 81 and with a host of health problems, including hearing loss, first learned of Gower’s students’ work to log war stories in 2013 when the Kennebec Journal wrote about one student’s effort to learn about a Rumford soldier who, like Lewis Goddard, is buried at Draguignan. Robert Goddard contacted Gower, who invited him to come and share his brother’s story. Goddard, who has scrapbooks of his older brother’s life, extending into childhood, has returned several times since. He and the students have forged a bond sealed by the mutual admiration they feel for Lewis Goddard.

“I’m in awe of them,” Robert Goddard said. “I’ve taken Maranacook High School and put it under my wing.”

Taking the students under his wing is a fitting metaphor to use when telling the story of his brother, who as a boy and young man gained a reputation for being able to nurse injured birds back to health.

Lewis Goddard, in many ways, led a storied life even as a child. He once was hiking with a friend whose legs were crushed in a cave collapse. Robert Goddard went and got help and returned to help his friend until that helped arrived. His quick-thinking, compassionate response earned him a prominent feature in the local newspaper.

Later on, he was one of the top four students in his high school class of 250 in Tennessee — he joined the Signal Corps Enlisted Reservists before he could graduate — where he was the first president of the hiking club and a member of a host of other clubs, including sketch, debating and dramatics and glee.

His love for and understanding of the outdoors lead to an invitation to the dedication of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park during which President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave the keynote address.

Goddard, who solicited letters of reference for the signal corps, was described by prominent members of the community, including the high school principal and city postmaster, as energetic, enthusiastic and exceptional.

Carlos Campbell, a family friend and agent with Provident Mutual Life Insurance, said Goddard was mature beyond his years.

“He is a young man of unusual integrity,” Campbell wrote.

LETTERS HOME

In January 1943, Goddard was sent to Lafayette Trade School in Lexington to learn how to be a radio operator. He finished training in June and was sent home to await basic training.

A letter sent from his father, Carlyle Goddard, in February 1943, tries to counsel his boy on his first foray away from home.

He urged his son to be careful and live up to the ideals instilled in him and to work hard and be cheerful. The father asks his son to write as often as possible, but to always write to his mother, Elva Goddard, first.

“She loves you very much, my son,” Carlyle Goddard wrote. “Much more than you will ever know. And worries about you continually.”

The father reminds his son that everyone has to leave home sometime and that the separation is often accompanied by pain.

“Just let me remind you that there are times which a strong man should not be ashamed to cry,” Carlyle Goddard wrote. “This is one of them. When you have this sort of sickness … have a good cry and it will help. I speak from experience.”

Lewis Goddard was ordered into active service in July 1943. Robert Goddard recalled his older brother taking him out the day before he left. His brother bought him a toy sail boat, and the two scarfed down 12-cent hamburgers.

“That was the last meal we ate together,” Robert Goddard said.

A few months later, in October 1943, Lewis volunteered for duty in the Office of Strategic Services. Two months after that, he was shipped to England and later Scotland for special training for the Jedburgh team.

Lewis Goddard apparently followed his father’s urging to write home at least once a week and apologized when there was a delay. He told his family about trips to explore Washington, D.C., and New York City.

“We were supposed to make our wills,” he wrote in a letter dated December 1943, when he was 19, “but I didn’t have anything to put in one.”

His thoughts often turned to his little brother. Lewis Goddard urged the boy to continue to feed and take care of his animals.

“You be a good boy and do your best,” he wrote.

Goddard always asked about family, fretted when he didn’t get a letter from his girlfriend, and spoke often of his longing for home.

He wrote of one happy visit he had in his dreams and looked forward to the day when it would come true. The same letter, from December 1943, references the holiday he will soon miss.

“I sure wish I could be home for Christmas, but it looks as if I will have a different kind of Christmas this year,” he wrote. “Maybe I can get home by next Christmas.”

Lewis Goddard died nine months later.

SECRET MISSION

After nine months of training and just a couple of months after the D-Day invasion, Goddard’s team got the call to go into battle.

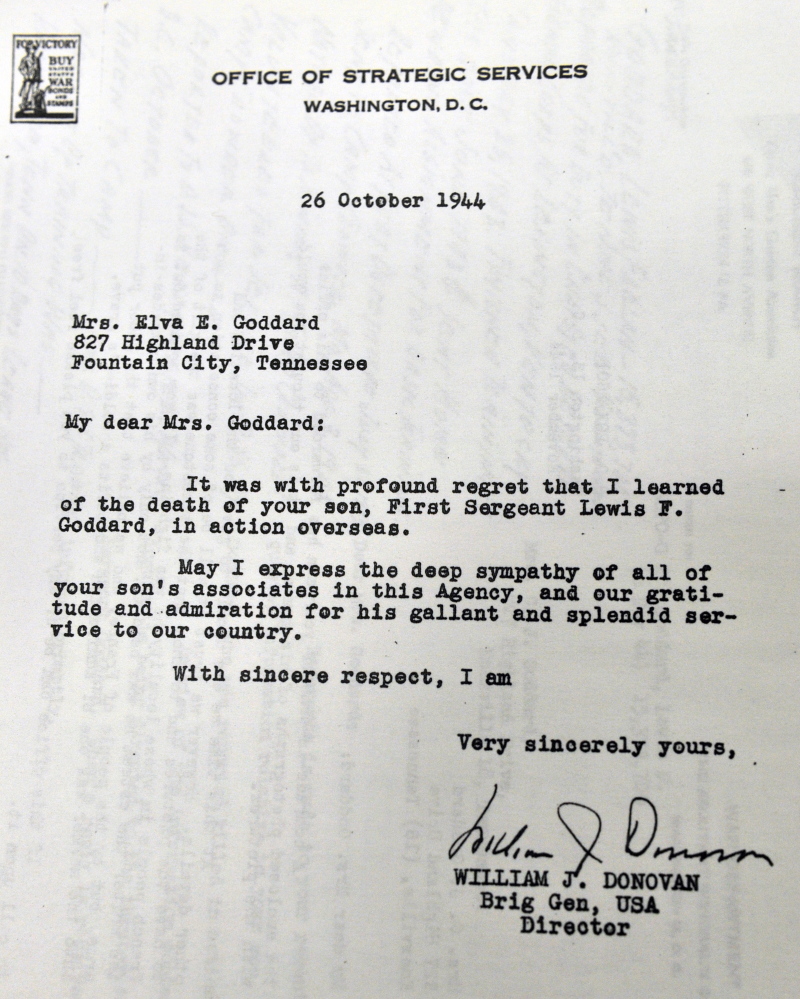

There were 99 Jedburgh teams, each consisting of three specially trained volunteers from the United States, England and France. Lewis Goddard could never tell his family about his work. It was all classified. His death did nothing to alleviate the family’s information blackout. In the same telegram dated Aug. 21, 1944, to Carlyle Goddard announcing his son’s death, Gen. James Ulio asks the family to keep their grief to themselves.

“Sgt. Goddard was performing duties that make it imperative that no publicity be given to his death,” Ulio wrote. “It is therefore requested that this information be divulged to no one outside your immediate family.”

Ulio wrote that he regretted the request, but assured the family that it is “in the best interest of our country.”

“Please accept my sincere sympathy in your bereavement and my appreciation for your cooperation in this matter,” the general concluded.

Robert Goddard, sipping coffee at Dave’s Diner in Gardiner last week, still marvels at the request and his parents’ ability to grant it. His parents told his siblings about Lewis Goddard’s death, but kept Robert, who was only in second grade, in the dark.

“It was months before they could let it be known,” Goddard said. “People would ask, ‘How’s Frelan?’ and they’d say, ‘He’s doing fine.'”

Elva Goddard, in a 1974 story in The Knoxville News-Sentinel, recalled the burden she and her family had to carry alone. Carlyle was away at a munitions plant, and two other children were away in the service, when she got the telegram. That left one daughter on whom Elva Goddard could lean.

“It was difficult,” she said. “I would just have to evade the answer. I’d usually tell them something to the effect that I had just not heard from him lately.”

The family knew nothing of the circumstances of Lewis Goddard’s death for months, and even then information came in dribs and drabs.

A letter dated August 28, 1944, from Lt. Col. Charles Rawson repeated the request for secrecy and claims any publicity could “jeopardize the safety of his fellow workers.”

Finally, a letter from Lewis Goddard’s Jedburgh teammate, John Cox of England, arrived at the end of 1944 explaining what likely happened. Goddard was killed in an accident when he jumped.

Cox, in a letter to Elva Goddard two years later, expressed affection for her son.

“I often think of Lewis and what a grand fellow he was, always cheery and efficient and willing,” Cox wrote. “It must have been a dreadful loss to you, as it was to me. I shall never forget what a good lad he was.”

A letter dated November 1944 from Maj. Charles Eubank shed more light on what happened to Goddard and contained a photo taken by Goddard’s friend of the 7-foot hand-carved oak grave marker made for him in Beddes. The major said he could not give the location.

“However, we trust it will be of some consolation to you to have the picture and to know that the tombstone was the gift of the French people in whose locality he was fighting,” Eubank said. “We believe the labor put into the marker was one of admiration and befits a soldier’s grave.”

‘SENSE OF DUTY’

The pieces finally started coming together in 1969 when Robert Goddard, serving with the U.S. Air Force, was stationed in England.

He tracked down Cox and made his way to the French towns of Beddes and Chateaumeillant, where he found people who had witnessed his brother’s death.

They told the story about hiding the body from the Germans, who were so desperate for information that they chose a person at random and hanged him with barbed wire as a warning to the people. The people, despite the threat, refused to surrender Lewis Goddard’s remains.

When the Allied Forces pushed the Germans out of the area, the villagers gave Lewis Goddard a ceremonial burial and the cross to mark the grave.

French Resistance fighters gave Robert Goddard a fragment of his brother’s parachute and badges, but couldn’t find the cross.

When Robert Goddard visited Beddes again in 1973, this time with his mother and sister for a ceremony to honor Lewis, the resistance fighters gave them a hand-carved replica. The cross is on display at the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Museum at Fort Bragg, N.C.

The Maranacook students have been captivated by Lewis Goddard’s story. They have an obligation, they say, to make sure it never disappears. That’s the motivation behind creating the memorial.

“We feel like we know this stuff, and we need to somehow make the world aware of it,” student Johan Nel said. “I think this is a good way for us to do it because the plaque will stay for a long time. Long after we’re gone. If we could, we should do this for every veteran. It’s the least we can do.”

Nel is just a couple of years younger than Lewis Goddard was when he was killed. He said hearing about Goddard’s life has helped put his own in perspective.

“These people that are going to war, they are our age,” Nel said. “To me, that thought is insane.”

Kaitlyn Chick, of Readfield, said connecting the personal stories with the overall narrative of the war has given the loss a face.

“They’re not just soldiers,” she said. “They have other lives. They left so much behind, and they had so much waiting for them to come back.”

About half of the students in the class have a relative who fought in World War II. A majority have had a chance to talk to a World War II veteran. There are common themes that come out in those conversations.

“They all had a really strong sense of duty,” Nel said.

That sense extended to the home front where family members worked to support the war effort while keeping the nation operating.

“Everyone was involved in one way or another,” said Anne-Marie Ricker, of Readfield, who has studied the role of women in the war. “A lot of the work they did was more underground. They still felt such a sense of duty. Their husbands and all the men were gone, but they wanted to do anything they could.”

Robert Goddard, too, did what he could.

The students say one of the most touching stories they’ve heard recounts an event that came after Lewis Goddard was killed. A man, unfamiliar to the Goddard family, came to their door with an injured sparrowhawk.

The man had heard of Lewis Goddard’s gift with injured animals and was hoping he could rescue the bird. Robert Goddard, in a tribute to his brother, took the bird and nursed it back to health.

“When Mr. Goddard was telling us about this he was starting to cry,” Wicks said. “He was able to fix the bird. He did what his brother would have wanted.”

The day finally came to release the bird, Nel continued.

“I think, in his mind, he sort of saw the hawk as a chance to be close to his brother again,” Nel said. “So when it came time to move on, he was very torn about it.”

Goddard said he idolized his brother as a child and never really stopped. He spent the better part of his life gathering information on his brother and loves to tell others what he has learned. He pauses to collect himself when asked what it means that the Maranacook students have joined him in that effort.

“I love ’em,” he said. “That’s all that I can say.”

Craig Crosby — 621-5642

Send questions/comments to the editors.