Hemingway and Flaubert loved Paris, Jack London adored Alaska, Faulkner embraced Mississippi, and Steinbeck had his California. Manhattan? Manhattan is tattooed on the heart and art of Allan Stewart Konigsberg — aka Woody Allen.

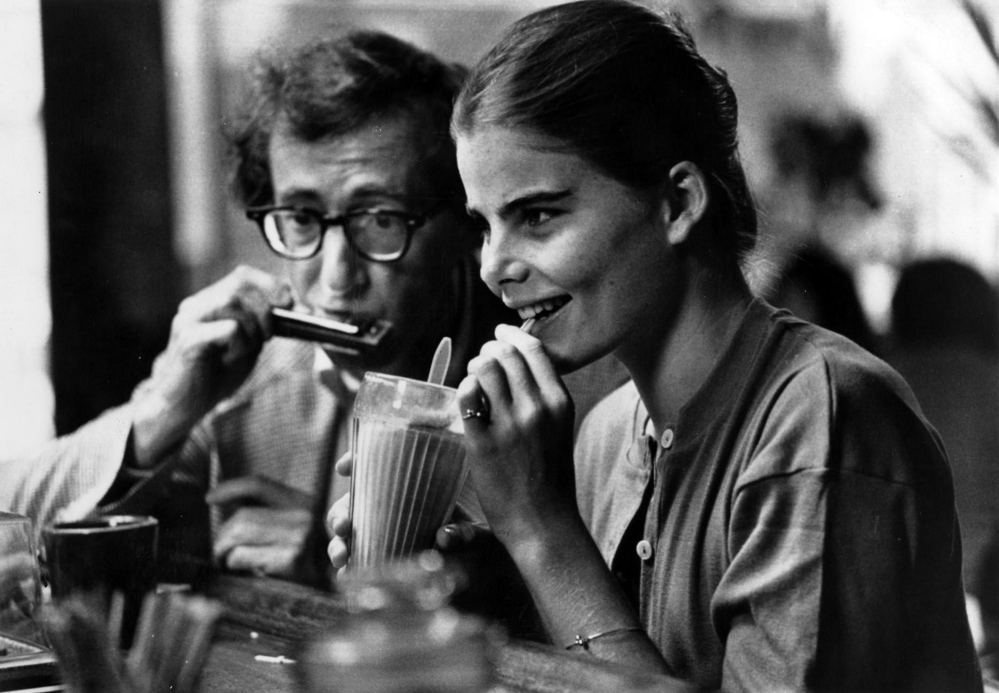

In none of his New York City films are the poetry of the city, the heartbreak, hysterical joy, loneliness and passion richer than in his 1979 black-and-white classic, “Manhattan.”

It’s Woody’s love song to his hometown, and he plays it on the black and white keys as though it were “Rhapsody in Blue.” From the opening to that final sweet and sad scene, it’s wall-to-wall Gershwin. Yes, it’s “‘S Wonderful,” and Manhattan will always be his “Sweet Embraceable You.”

Most of Woody’s later movies set in New York or Paris, London and Hollywood are full of brilliant color. But “Manhattan,” shot by the fabulous Gordon Willis, is in pure crystal — like black and white. For me, that’s the only way to do it, because the memories of all of us who have lived and worked there, fell in love and had our hearts broken there, are in black and white.

When people tell you about the billion colors of Manhattan, you know they’re tourists who have spent only three days there on summer vacation.

They remember the tulips on Park Avenue, the autumn colors in Central Park and the fashion-filled shop windows of Fifth Avenue. Woody truthfully gives us his lady dressed in black and white; the snowy brownstone steps; the chorus line of wet, black umbrellas in the first spring rain; the bags of trash on the street; and the white-as-a-sheet Manhattan skies. That’s Manhattan for many of us.

In this great classic, Woody is Isaac Davis, the hand-twitching, glasses-fiddling neurotic we’ve come to love, who has just quit his days as a hack writer for a television comedy. (Woody did just that as a writer for Sid Caesar’s “Show of Shows.”)

Free of the restraints of canned television for about 10 minutes, ostensibly to write his “book,” he’s already having buyer’s remorse. The problem is that our flawed hero is in deep debt. He pays alimony to two ex-wives, including his most recent one (OMG, it’s a young, gorgeous Meryl Streep before her 600 Oscar nominations), who left him for a woman, something he painfully tries to keep quiet but enjoys telling everyone. She is also about to publish a tell-all book about their marriage.

Meanwhile, Isaac enjoys a sweet upper East Side two-layer apartment, where he spends his evenings half-heartedly trying to convince his 17-year-old girlfriend, Tracy (a very young Mariel Hemingway. Remember Mariel Hemingway?), that he’s all wrong for her. But she’s trying to finish her homework so they can get to bed. I know. It sounds kinky, but this is Woody and Mariel.

If things weren’t complicated enough, he meets a sophisticated know-it-all journalist, Mary Wilkie (of course it’s Diane Keaton; you were expecting Myrna Loy, maybe?) while she is having an affair with his best friend, Yale.

And who could better play a character named Yale, the tweedy bespectacled epitome of the modern, confused Manhattanite, than everyman Michael Murphy?

Murphy serves as Isaac’s sidewalk conscience — until his own starts fracturing, and he turns to Isaac for advice. Isaac’s advice? What could possibly go wrong? Everything.

Murphy is perfect. Hemingway is wonderful. Streep? When has she never been perfect? Even the passers-by bumping into the players in the street are perfect, because they’re New Yorkers.

Yes, there’s Paris and London for many, “But Not For Me,” and not for Woody.

For Woody and the trillions of lovers who have bought roasted chestnuts from a stand on Times Square or small bunches of violets in the snow on Second Avenue, it’s our Manhattan, it’s Woody’s, and “Love is Here to Stay.”

J.P. Devine is a former stage and screen actor.

Send questions/comments to the editors.