Mickey Kline and Anthony Crame live in a tent camouflaged with ferns and hidden in a field of ragweed. As they slip into their tent for the night, they can hear the traffic on Valley Street, less than 30 feet away, as commuters drive past them on their way to their homes in the suburbs south of Portland.

“No one knows we’re here,” said Crame, 27, who has been homeless off and on since running away from a foster home at age 18.

All over Portland there are hidden campgrounds like this one – in the wooded areas adjacent to rail lines and highways, and in tunnels, alleyways, utility easements and overgrown vacant lots. The best-hidden campsites are more permanent, with couches and small vegetable gardens, while those in public parks are fleeting, appearing after sundown and gone by morning.

People who work with the homeless say there are more campers this summer than they’ve ever seen before.

“People are getting pushed farther and farther into the woods because there are more people camping out,” said Donna Yellen, chief program officer at Preble Street, a soup kitchen and resource center for homeless people.

Campsites that were once occupied by five or six people now have 15 or 20. The camps have sprung up in new places on the outskirts of the city because prized in-town sites are occupied or have been developed.

Nobody really knows how many campers there are. An accurate count is impossible because campers hide themselves to avoid being chased away by police, said Peter Driscoll, director of Amistad, a nonprofit that primarily serves adults with mental health issues. Vandals who tear up campsites also pose a threat.

Portland Police Chief Michael Sauschuck said the number of campers increases every summer. Police respond to complaints, he said, but they also check on campers to make sure they are safe.

In 2013, a homeless man in a wooded area on West Commercial Street died of smoke inhalation after his tent caught fire. That same year, a homeless couple on outer Washington Avenue were injured when a candle ignited their tent.

The city counts the homeless campers once a year, in January, when their numbers are at the lowest point because of the sub-freezing temperatures. In 2014, the city counted 10 people living outdoors, and the survey this winter found nobody. But Driscoll said the survey, required by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, is useless because the people they are counting are largely invisible.

“They particularly don’t want to be found,” he said.

Joe McNally, who manages a homeless outreach team run by the Milestone Foundation, said he passes at least four homeless encampments as he travels along Washington Avenue from his home near Canco Road to the Milestone facility on India Street.

Most people don’t know about them. “They are hidden in plain sight,” he said.

DEVELOPMENT PUSHES OUT CAMPSITES

Development has eliminated two prime spots on the peninsula. The “Hobo Jungle,” a stretch of woods behind the Cumberland County Jail, vanished when Mercy Hospital built its 42-acre Fore River campus.

Another secluded spot was Yard 8 – a nearly 20-acre parcel of overgrown vacant railroad land on West Commercial Street. But the trees were cut down to make room for a boatyard and the expansion of the International Marine Terminal.

This spring, 30 to 50 people were camping out in a large wooded area behind the Lowe’s and JoAnn Fabrics stores on Brighton Avenue. The trees are so thick that it could be the middle of the North Woods, except for the traffic noise from the Maine Turnpike.

But vandals attacked the site and ripped up the tents. The campers for the most part abandoned the area, McNally said.

Milestone has a two-person team that reaches out to the homeless. They check on their health and give them supplies, such as water, sunscreen and even tents on occasion.

Many of those who sleep outdoors don’t like the regimented environment in homeless shelters and prefer the freedom of living outside with their friends, said Milestone staff member Liam O’Reilly.

“There’s something about the shelters that doesn’t agree with them,” said O’Reilly, a recovering addict who has spent years traveling around the country on freight trains and living outdoors.

REGION’S POOR CONTINUE TO STRUGGLE

There is no obvious explanation for the increase in homeless campers, say social service providers. They see it as another indication that the region’s poor continue to struggle despite the growing economy. Cuts in social services programs under the LePage administration have weakened the social safety net, they say.

The increase in homeless encampments is just one example of how desperate some people have become, Yellen said.

She points to the loss of federal food stamp benefits to childless adults between the ages of 19 and 49 who don’t have a disability, and Medicaid cuts in Maine that have caused thousands of people to lose access to health care. Those cuts also have reduced access to the state’s substance-abuse treatment system. Even relatively small cuts, such as new limits for using bus passes for medical appointments, make it harder for the poor to get around the city, she said.

“People are falling quickly and hard,” she said.

Preble Street Executive Director Mark Swann agrees.

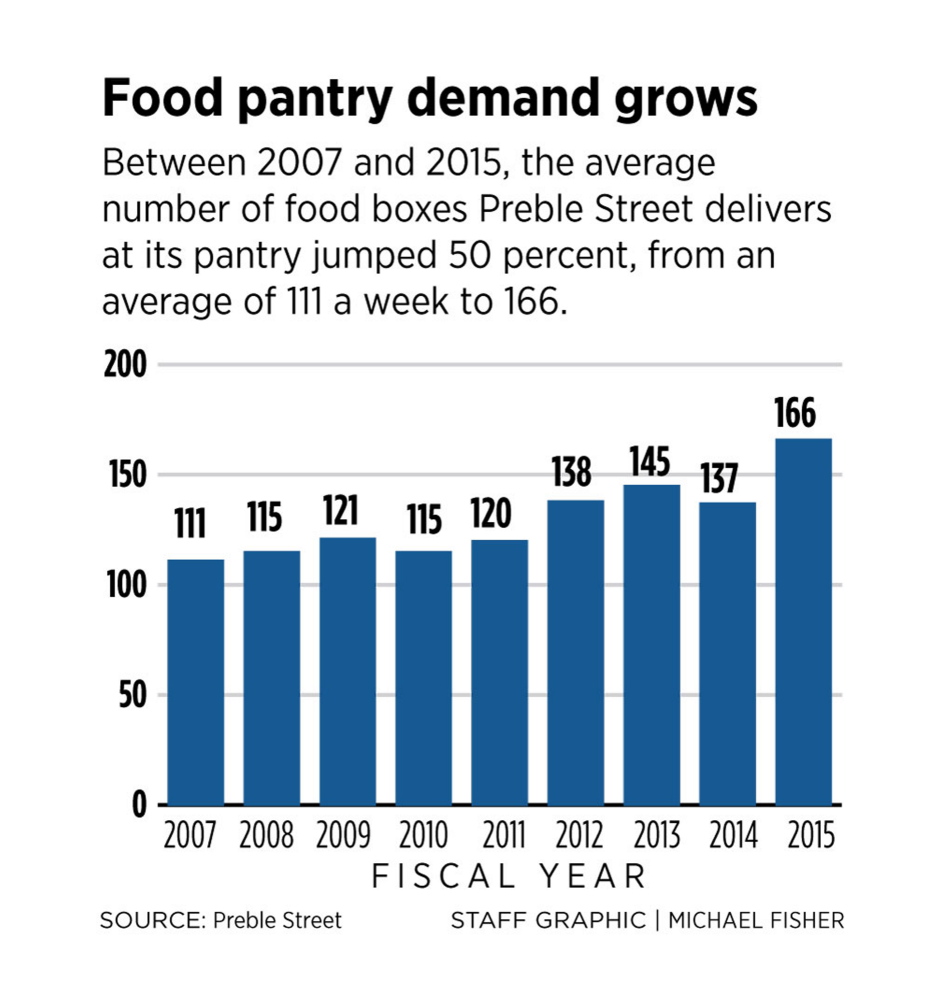

From 2007 to 2015, the average number of food boxes that Preble Street delivers at its pantry jumped 50 percent, from an average of 111 a week to 166.

“I think there’s an impression that there’s a healthy social compact where people can get the help when they need it, and that’s so not true,” he said. “The human service network is being wrenched apart.”

Portland’s homeless population increases in the summer as people travel to Maine in search of seasonal jobs and also to escape the heat in other parts of the country.

The city-run Oxford Street Shelter is crowded this summer, but not any more than usual for this time of year. This June, an average of 211 people slept each night at the shelter, compared with 213 people in June a year ago. Shelter director Angela Havlin says there’s been a bigger effort in the past year to find permanent housing for a group of homeless people who stay at the shelter more than 180 days a year.

HOMELESS CAMPERS ARE MORE ISOLATED

People who are living outside give various accounts for why they don’t go to a shelter. A common complaint is that the Oxford Street Shelter has bedbugs.

“The bedbugs will pick you up and carry you away,” said Shawn Anderson, 40, who has been camping for a month in Portland in several locations.

That complaint has some validity. Havlin said a pest control contractor treats the facility every month but it can’t control what people bring in on their clothing and belongings. Although there are bedbugs nightly, she said, the pest control contractor reports that the activity is not significant.

Some of the campers say they feel anxious about being around so many people in tight quarters. Some feel unsafe. Others complain the shelter’s rules are too strict.

Driscoll, from Amistad, said some of the homeless don’t feel welcomed at the shelter.

“The problem from my point of view is that some folks find the shelter really intimidating, not friendly,” he said. “They don’t want to be there.”

People who camp out are more isolated and harder for social workers to monitor and to help, he said.

“We have an obligation to reach out to them where they are,” he said. “You don’t necessarily expect them to come to you.”

Another contributing factor is the separation of couples because the city’s shelter system is not set up to accommodate them. The Oxford Street Shelter puts men and women on different floors, and some couples say they prefer to sleep outside so they can stay together.

For Joy Mulvihill, 43, and Peter Goding Jr., 46, home is an eight-person tent in the woods in Sanford. But after Mulvihill was taken to a hospital in Portland earlier this summer for treatment of alcohol poisoning, they have been living in a park using a tent made with woolen blankets.

“They separate us at the shelter,” Goding said. “We want to be together.”

In the shelter, people sleep on floor mats that are assigned at random. Kline and Crame, who are living in a tent near Valley Street, are a gay couple. They say they don’t like the shelter because they are usually assigned to mats in different rooms.

They have been living outside since they became a couple in April, first in a secluded area on the slope between Marginal Way and Washington Avenue. But their campsite earlier this month was wrecked by a gang of teenagers. That’s when they moved to a site near Valley Street.

Kline is working full time driving a van for a day-labor company, but he hasn’t been able to save money because of a debt to a storage facility. The couple hope to get an apartment before winter comes by qualifying for a Section 8 voucher.

“We want to live our lives like normal people,” Kline said.

In a wooded area near the Maine Turnpike, a couple prepare for the night in a tent hidden under a brown tarp and tree branches. It looks like a mound of dirt. The camouflage saved the tent from damage this spring when vandals ransacked other tents in the area, said one of the occupants, Terry Walters, 55.

She said she scavenges for food at a nearby dumpster and panhandles for cash. She and her husband were evicted from their apartment two years ago after falling behind on their rent. Walters said she suffers from bipolar disorder and gets anxious when talking to landlords while looking for an apartment.

The couple moved from the Oxford Street Shelter to the woods so they could sleep together. When winter comes, they might live in the woods rather than return to the shelter, Walters said. But what the couple really want, she said, is an apartment.

‘We don’t want to be in a shelter,” she said. “We want to be out. We want a place to live.”

HOMELESS SOMETIMES ‘A NICE WAY TO LIVE’

For some campers, living outside is a lifestyle choice. That’s the case with Matt Coffey, who lives in an expansive wooded area on the outskirts of Portland. Coffey, who works as a landscaper and is saving money to buy his own land, asked a reporter not to disclose the location.

He has lived there for three years with his cat, Slinky. Inside his home – an elaborate system of tarps – there’s a fireplace for cold winter nights. Smoke escapes through a gap at the top. He has planted a garden with corn, tomatoes, cucumbers and sunflowers. To irrigate his garden, he’s digging a well in a vernal pool.

He lives in the city limits but is surrounded by trees.

“I call this the 100-acre wood,” he said “It’s really a nice way to live.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.