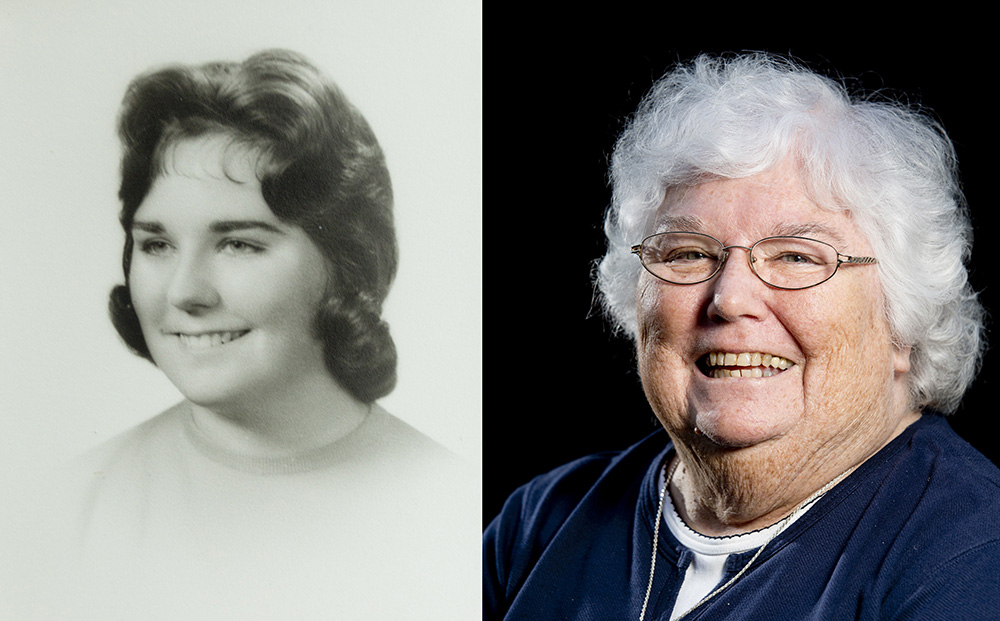

Emotions ran high the day 18-year-old Annemarie Kiah traveled from Brewer to Portland to join the Sisters of Mercy.

It was Sept. 23, 1958. Her family piled into the Chevy sedan and headed south. In her suitcase was a plain black dress with white collar and cuffs, purchased in Boston that summer and ready for her arrival at St. Joseph’s Convent.

A flat tire early in the trip heightened the tension. She just had to get to the Motherhouse on Stevens Avenue before the sisters locked the door at 4 p.m. Back on the road, her father stared straight ahead. Her mother was in tears.

“She cried all the way down to Portland,” Kiah recalled. “She was happy for me, but she knew we wouldn’t see much of each other after that. My dad was probably thinking he’d never get to walk me down the aisle.”

That stressful journey was Sister Annemarie Kiah’s first step in what would be a long and fulfilling career as a teacher of about 1,300 children at 11 different parochial and Native American schools across Maine from 1962 to 2010.

Now 75 and still active as a volunteer at Mercy Hospital in Portland, Kiah is one of 66 Sisters of Mercy in Maine who are celebrating the 150th anniversary of their order’s founding in this state on Aug. 5, 1865, just four months after the end of the Civil War. Others who share their stories here include a retired sister who taught for 31 years on a Passamaquoddy Indian reservation, a sister who lived and worked for a decade in Peru before returning to serve Maine’s growing Hispanic population, and the last sister to join the order in Maine more than three decades ago.

Once numbering several hundred women in the 1960s, the Sisters of Mercy played a crucial role in the growth of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland and the development of cities and towns across Maine. They started and staffed schools, orphanages, hospitals and other institutions in 25 communities from Sanford to Eagle Lake.

Their numbers have fallen along with church membership, which is down from 286,408 people in 1990 to about 175,000 today, according to the diocese. Still, 150 years after their arrival in Maine, the sisters are devoted to helping people in need – the young, the poor, the sick, the abused and the elderly – through service and prayer.

Twenty sisters are active in full-time ministry in the fields of health care, education, social welfare and pastoral services, said Sister Mary Morey, the order’s Maine coordinator. Other sisters are either semiretired or retired, but they remain active as volunteers or in prayer for sisters and others who are addressing the order’s critical concerns, which include racism, women’s issues, immigration reform and the environment.

Unlike cloistered nuns, the sisters work and live in their communities, in houses or apartments provided by the order, which led them to close the Motherhouse in 2005. The order’s formal affiliations in Maine are now limited to Saint Joseph’s College in Standish, Mercy Hospital in Portland and Catherine McAuley High School in Portland, an all-girls parochial school named for the woman who founded the order in 1831 in Dublin, Ireland.

But signs of the sisters’ past and continuing work are still apparent in many Maine communities, from the McAuley Residence for women and children in Portland to the public Beatrice Rafferty Elementary School on the Pleasant Point Indian Reservation in Perry, which is named for a sister who was a longtime teacher and principal.

Bishop Robert Deeley celebrated the sisters’ accomplishments during a 150th anniversary Mass on Friday at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Portland. Other special events have been held throughout the year and a memorial garden will be dedicated in September at St. John’s Church in Bangor, where the sisters established their first convent and school in Maine.

“The Sisters of Mercy have left their mark in so many ways,” Deeley said in a written statement. “Whether in health care or education or social work, the lives of thousands of people have been greatly improved by the wonderful care of the sisters over the 150 years they have ministered in the Diocese of Portland. The Catholic Church in Maine owes a great debt to the Sisters of Mercy.”

Among the most significant contributions made by the Sisters of Mercy were the schools they established in the late 1800s on the Penobscot Indian Reservation at Indian Island near Old Town, and on the Passamaquoddy reservations at Pleasant Point and Indian Township in Washington County.

“There was a time when there would have been no education on the reservations if it weren’t for the Sisters of Mercy,” said Rick Phillips-Doyle, a Passamaquoddy who is a deacon of the diocese. “They educated (our) people when the state wouldn’t. They became part of the community and were mentors and friends to many of us.”

DEDICATED TO PASSAMAQUODDY EDUCATION

Sister Maureen Wallace spent 31 years as a teacher and principal at Pleasant Point. But she was less than eager to join the Sisters of Mercy when she graduated from Cathedral High School in Portland in 1961.

“I actually felt I had a calling, but I prayed not to have it. Isn’t that awful?” Wallace recalled, laughing now at the thought of it.

But she had admired the sisters all through school, so she sent an application to the Motherhouse, despite her mother’s opposition.

“My mom didn’t want me to go,” said Wallace, 72, of Portland. “When the acceptance letter came, she hid it. When I asked about it, she said, ‘They probably don’t want you.’ But other girls were getting their letters, so she finally had to give it to me. Then she wouldn’t sign the consent form. When my dad signed it for me, she said to him, ‘You’re signing her life away.’ ”

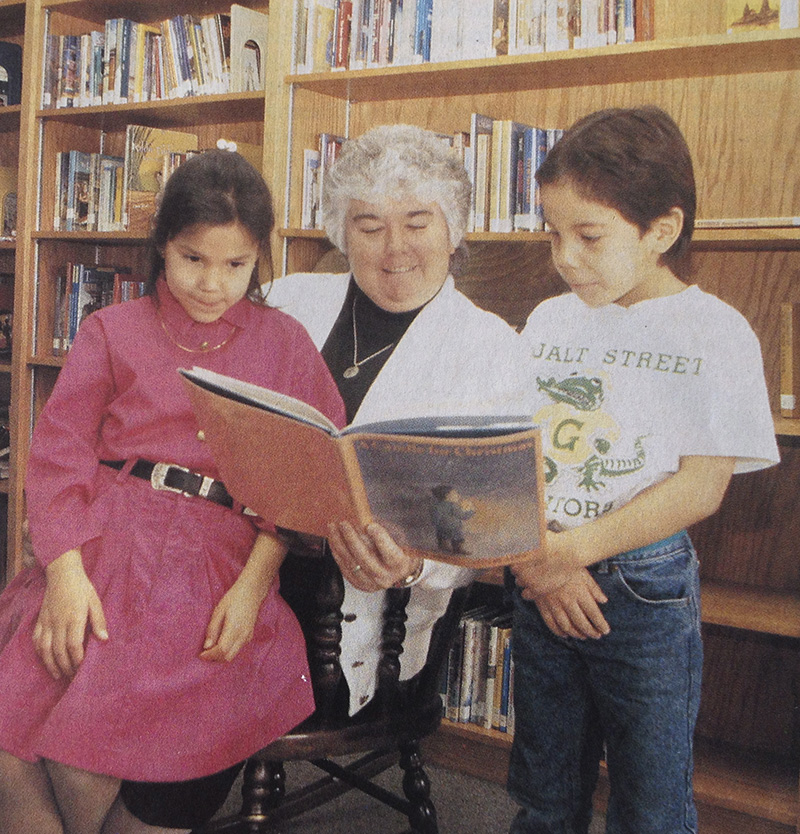

Wallace got a teaching degree from Saint Joseph’s College and went to work at Pleasant Point.

“They were like family to me,” Wallace said of the Passamaquoddy people. “I was young when I went up there and I grew up with them. I loved it from the minute I started. I felt so accepted. I felt that they contributed to me.”

When a Passamaquoddy girl needed a foster home, she lived at the convent for six months. Now, that girl is in her 30s and a mother of three. She and Wallace remain friends.

“She had been in several foster homes,” Wallace said. “It was a privilege, really, to help her get to a good place.”

Wallace recalled another child’s statement, made years ago, that still touches her heart.

“One student told me, ‘Sister, you should have been a mother,’ ” Wallace said. “That was the best compliment because I think motherhood is so important.”

Over time, Wallace’s own mother grew to accept her decision to join the Sisters of Mercy. She even spent summers at Pleasant Point, living at the convent with her daughter and getting to know tribal members. The sisters regularly joined in Native American cultural and spiritual events, including funerals, dances and other gatherings.

When Wallace’s mother died in 1999, at age 94, several tribal members traveled to Portland for her funeral, where they played traditional drums and sang a Passamaquoddy honor song.

“It was very spiritual,” Wallace said, swallowing her emotions. “To this day, if I hear those drums or the Passamaquoddy language, I fill up.”

Wallace recently retired as coordinator of the Sisters of Mercy in Maine and now tutors students at Riverton Elementary School in Portland.

“It’s not really retiring,” Wallace said. “We have to find something else to do.”

‘I SAW WHAT THE SISTERS WERE DOING’

Sister Patricia Pora grew up in Chile, where her American father worked as a scientist. He believed she should have an American education, so when she was 16, he sent her to live with a former colleague in Windham.

She met Sisters of Mercy when she volunteered to help them teach prison inmates how to read braille so they could translate children’s books. She graduated from Windham High School in 1967 and joined the sisters that fall.

“I saw what the sisters were doing and I liked it,” said Pora, 67, of Portland. “It was service tied to the Gospel. It’s not that I didn’t want a family, but I felt that having a family would tie me down.”

Pora first became an X-ray technician at Mercy Hospital, then a teacher at Pleasant Point. She saw firsthand how Passamaquoddy Indians struggled against prejudice and discrimination.

“The train went by the reservation, and it was supposed to be a regular stop,” Pora said, “but (the engineers) would just slow down and let the Native Americans jump off.”

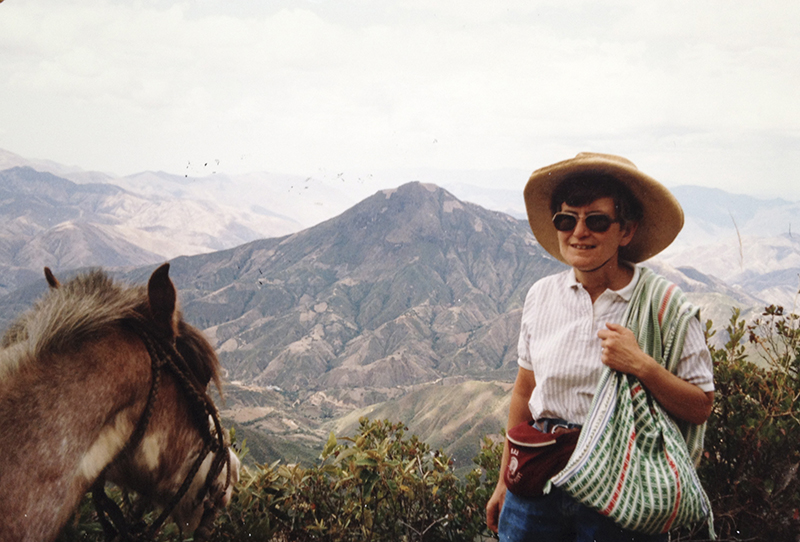

Pora taught at Pleasant Point for about a decade before transferring to a parish in Pacaipampa, Peru, where she served a mountain community of 24,000 people spread among remote farming villages. She collaborated with health workers to provide social, spiritual and medical care. Many villages could only be reached on foot or by mule.

“We went on 10-day rounds and stayed in schools or people’s homes – wherever they could put us,” Pora said. “We showed them how to sew up machete wounds and use antibiotics. We also showed them how to use pesticides, because they didn’t know how to use them properly and we had many pesticide poisonings.”

Pora returned to Maine in 2002 and soon after established a Spanish-speaking ministry for the state’s growing Hispanic population. Today, Pora is one of five people – including two sisters and a deacon from Central America and a laywoman from Peru – who provide pastoral outreach and social advocacy to more than 18,000 Hispanic people in Maine.

The diocese offers weekly Spanish Masses year-round at Sacred Heart Church in Portland and Saints Peter and Paul Basilica in Lewiston, and seasonally for migrant workers at St. Michael Mission in Cherryfield.

“It’s a very faithful community, but it’s a mostly hidden population,” Pora said. “They try to stay out of the public eye and they do the work that nobody else wants to do, but many of them are underserved. We provide pastoral care and a bridge to the services they need.”

THE LAST SISTER TO JOIN IN MAINE

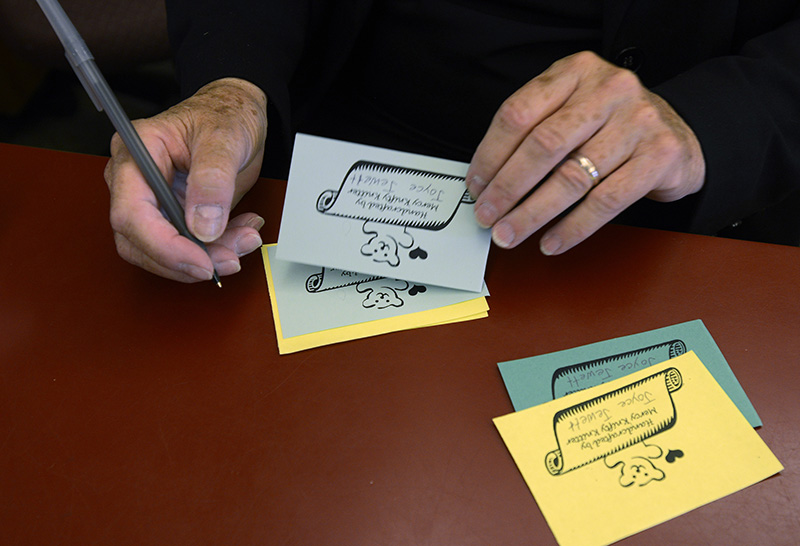

Sister Carol Lachance is the last woman to have joined the Sisters of Mercy in Maine.

A basketball star at Gorham High School and Saint Joseph’s College, Lachance joined the order in 1983, the year before she graduated with a bachelor’s degree in business administration and sociology.

“When I went to Saint Joseph’s, I thought I would meet someone, get married and have a family,” said Lachance, 54, of Portland.

Lachance was drawn to the work that she saw the sisters doing at the college and throughout Greater Portland, especially related to social justice. She also admired the legacy of Catherine McAuley and the work she did for the poor and other marginalized populations of Ireland. Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, Lachance appreciated the sisters’ concern for minorities and women’s rights around the globe.

She was reluctant to join until one day, when she attended a campus Mass and heard a folk group singing, “Be not afraid, I go before you always. Come follow me, and I will give you rest.”

“I heard that song and I felt a sense of peace within,” Lachance said.

She lived and worked on the Pleasant Point Reservation for more than a decade, starting an after-school program, working as the school librarian and serving as the resident services coordinator for the tribal housing authority. But her “real ministry” happened off the clock, helping families cope with challenges ranging from unemployment to addiction.

“You’re living within a community, not as a tribal member, but as an advocate, friend and soul mate,” Lachance said. “I was actually living what I was experiencing in prayer and in Scripture.”

When Lachance took her final vows in 1993, three Passamaquoddy women traveled to Portland to participate in the celebration, burning dried sage as a traditional Native American smudge blessing.

More recently, Lachance served as director of the McAuley Residence for women and children, a teacher at St. Patrick’s School in Portland and campus minister at Catherine McAuley High School. She is now resident services coordinator at Deering Pavilion in Portland, a diocesan-owned residence for retired and disabled adults.

The order’s social justice mission still inspires Lachance, who regularly signs petitions, writes letters to elected officials and attends public demonstrations on issues ranging from domestic violence to homelessness to immigration reform. And always, there is prayer.

“I continue to get revved up about social justice,” Lachance said. “I went to Washington, D.C., last year to lobby for an immigration bill. We all try to do all those things because it’s central to who we are as sisters.”

TRIP TO MOTHERHOUSE LED TO LIFE’S WORK

Annemarie Kiah had no interest in becoming a sister when, during her junior year at the then-parochial John Bapst High School in Bangor, she accompanied three friends on a trip to the Motherhouse in Portland.

“I wasn’t thinking about becoming a sister,” said Kiah, of South Portland. “I wanted to be an airline stewardess or a secretary. But my friends were interested in joining the sisters, so I went with them.”

By the time she graduated from high school, her calling was clear. Kiah and her three friends were among 17 young women who joined the order that fall. Kiah’s friends left the order before taking their final vows. Today, only four of the initial 17 women are still sisters. Many left during the 1960s and 1970s to get married or for other reasons, Kiah said.

Throughout her career, Kiah taught first- through third-graders at tribal and parochial schools in Biddeford, Rumford, Indian Island, Lewiston, Pleasant Point, Bangor, Indian Township, Portland and South Portland.

“I loved the children,” Kiah said. “When they started to learn, it was such a joy.”

She had a firm but loving approach, telling students on the first day of school, “You be good to me and I’ll be good to you.” She also said she wanted them to be in bed by 8 p.m., warning them that she’d call each student’s home once during the school year to make sure they complied. When she did call, students boasted the next day in class and she rewarded them with stickers.

“They loved it,” Kiah said. “If they got to bed early, they came to school fresh and ready to learn.”

Like most sisters, Kiah made prayer a regular part of the school day. Whenever students heard a firetruck or ambulance siren, she would stop the lesson and they would recite a simple prayer in unison: “Dear God, help the person who needs help. Amen.”

“We did that to get them to think about other people, to show compassion,” she said. “Today, I run into former students who tell me they still say that prayer every time they hear a siren. ”

Prayer remains a significant part of Kiah’s life. She rises at 4:45 a.m. each day and prays for about an hour. Her devotion is focused on people in the community. Some have asked for her intercession. Most have no idea she’s praying for them. Insurance agents and police officers. Doctors and politicians. Teachers and students. And of course, the downtrodden.

“We believe prayer can move mountains,” Kiah said. “No matter what we do, it’s ingrained in us to care for other people.”

Unlike most Sisters of Mercy, however, Kiah still wears her habit whenever she volunteers at Mercy Hospital or attends church-related events.

“I still love it,” Kiah said of her neat, black dress. “I’m so proud of showing that I’ve dedicated my life to something special. And when I wear it, I can’t tell you how many people say, ‘It’s so nice to see a sister.’ ”

Send questions/comments to the editors.