FARMINGTON — From two motorists who say police violated their rights after traffic stops, to a Skowhegan man who says the state misled him on when he had to label his deer stand, Mt. Blue High School students got to see Maine justice in action Wednesday morning.

“Welcome to the Maine Supreme Judicial Court,” boomed Mt. Blue High School Principal Bruce Mochamer to a packed audience of students and faculty members at the school’s Bjorn Auditorium.

As local attorney Paul Mills prepared the crowd of high school students for the judicial process they were about to witness, the lawyers who were presenting their oral arguments sat at tables on the floor of the auditorium, looking over their briefs and preparing their arguments. For them, this was just another day of appealing their clients’ cases to the highest court in Maine.

But for the students, it was a rare chance to see the state’s highest court operating, thanks to Sen. Tom Saviello, of Wilton, who’d been engineering the appearance for four years. It’s part of the court’s program to visit local schools, and it was at Hermon High School on Tuesday and will be at Scarborough High School on Thursday.

Student chatter fizzled to silence in the auditorium when the court clerk called for the audience to rise as the seven justices took their places at a makeshift judicial bench on stage.

“You may be seated,” Chief Justice Leigh I. Saufley said.

Saufley sat with her associates, Justices Jeffrey L. Hjelm, Ellen A. Gorman, Donald G. Alexander, Andrew M. Mead, Joseph M. Jabar and Thomas E. Humphrey, and then introduced the lawyers who were presenting the morning’s first case: State of Maine v. John E. Sasso.

Court was now in session.

FOURTH AMENDMENT ISSUES

Mills, whom Alexander called the leading legal historian in Maine, briefed students on what each case would be about, alerting them they would see the Bill of Rights used as a defense, as well as state statutory liability.

The first two cases, State of Maine v. John E. Sasso and State of Maine v. James Morisson, both involved Fourth Amendment claims alleging unlawful searches. Attorney Ezra Willey, representing the appellant in both cases, told the court that his clients’ constitutional rights had been violated by unwarranted police stops.

Sasso was pulled over in Ellsworth because one of the brake lights on his vehicle was brighter than the other. The traffic stop resulted in the discovery that Sasso was operating his vehicle without a license. Willey argued that the officer, who was working on an underage drinking detail, pulled Sasso over because he was a young male who the officer suspected could have been drinking and used the tail light as a reason to stop the vehicle.

Hancock County Assistant District Attorney Dewlyn E. Webster argued that an officer can pull over a car if the vehicle’s lights appear to be malfunctioning. Willey rebutted that the lights were functioning. However, the court pointed out that the previous court that heard the case already had ruled on these matters of fact, and that the high court can rule only on matters of law.

In the second case Willey asserted that Morisson was wrongfully pulled over in Dover-Foxcroft for erratic driving, which resulted in a charge of operating under the influence.

Just as with Sasso, Willey argued that Morisson was subjected to an unwarranted search, claiming that the erratic driving exhibited by his client was because of poor road conditions and frost heaves that forced Morisson to cross into the oncoming lane.

Willey asserted that the officer should have taken the poor road conditions into consideration before pulling Morisson over, resulting in the issuing of the “unwarranted search” — the intoxilyzer.

Piscataquis County Assistant District Attorney Tracy Collins, representing the state, defended the officer’s judgment in pulling over the vehicle, stating that if a car had been coming from the opposite direction, public safety would have been in danger.

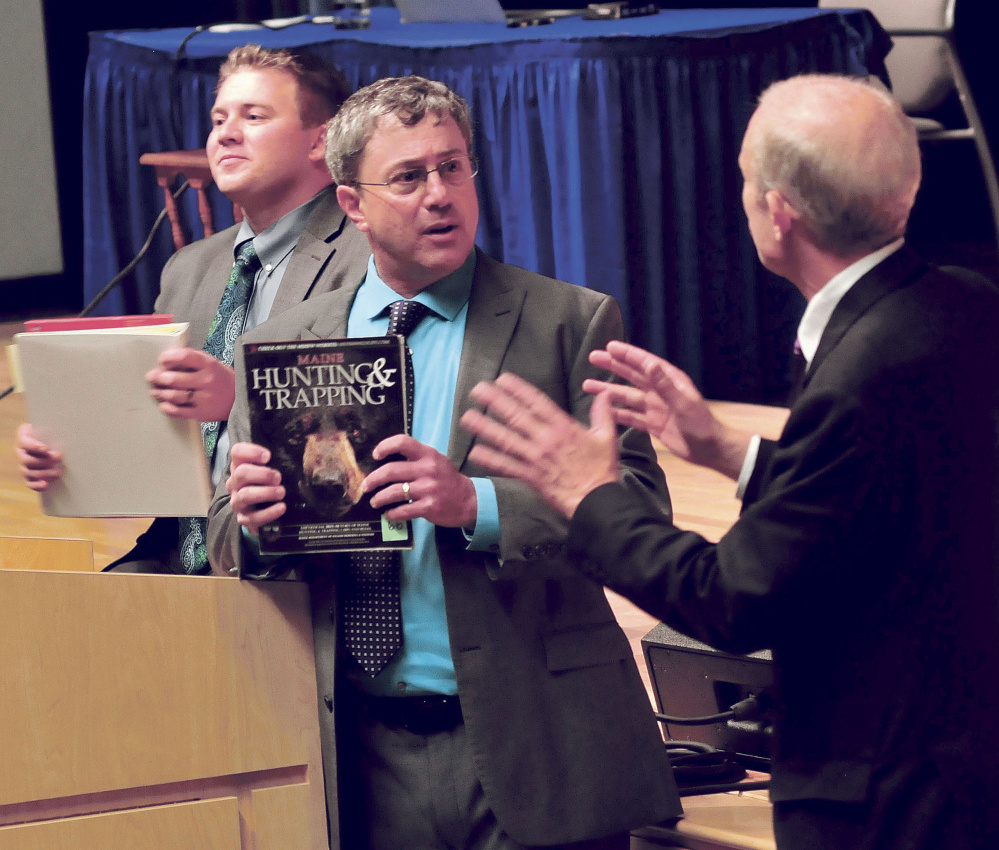

The final case, State of Maine v. Harvey Austin Jr., involved the grammar of a Title 12 statute that was summarized in a Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife magazine, “Maine Hunting and Trapping,” which involved appropriate tagging of tree stands used for deer hunting. The magazine was given to Austin when he got his hunting license, and his lawyer has argued the implication is that hunters can learn hunting laws from the magazine.

Austin’s attorney, Skowhegan lawyer Lawrence P. Bloom, argued that the wording in the DIF&W magazine was misleading and led Austin to believe that he only had to tag a tree stand he put up on someone’s property if he was using the stand, which he said he wasn’t.

Maine game wardens in November 2013 found a stand on Old Pond Road in Skowhegan that wasn’t labeled and later found it belonged to Austin. Austin argued in his August 2014 trial that he wasn’t finished with the stand and hadn’t used it, and that the law says “to erect and use.”

Austin was criminally charged for failure to tag his tree stand, a class E misdemeanor, because the state statute requires tree stands to be tagged whether they’re in use or not.

Francis J. Griffin Jr., the state prosecutor in this case, said the state statute as it was written in law is what counts, not what’s summarized in the magazine, arguing that common logic would have had Austin tag the tree stand whether he was using it or not.

STUDENTS’ TURN

While the students will not know the result of the cases immediately — the court issues rulings later and will send students the link to its decisions — they were given the opportunity to ask the lawyers questions about the cases at hand or the law process in general.

One female student, who said she was intrigued by the role that grammar played in State of Maine v. Austin, asked the lawyers if grammar experts were ever consulted on drafting briefs.

“The grammar expert is a judge,” Griffin said.

Griffin told students that misinterpretation cases such as the one they had just witnessed were common, elaborating on the fact that how a law or statute is interpreted is left up to judges.

One student took on Willey’s argument that his client’s rights were violated in State of Maine v. Morisson by asserting, “Wouldn’t you say that swerving into the next lane endangered the public safety, therefor violating the rights of other people?”

To this, Willey agreed that there is a fine line between when to violate someone’s rights to protect the rights of others.

“It was a great educational experience for our students and for our staff as well,” Mochamer said at a lunch with the justices that was held after the conclusion of the three oral arguments.

Students of Mt. Blue’s culinary program prepared and served the food served at lunch, which was an opportunity for 12 randomly selected honors history students to sit down and talk with the justices.

FIRSTHAND LESSON IN JUSTICE

Wednesday’s proceedings were a part of the court’s program to bring the judicial system into the halls of Maine’s public education institutions. By holding oral arguments that the justices usually would hear in their Portland chambers in front of student audiences at their own schools, the justices hope to demonstrate to students firsthand how the judicial system really works.

“We’re fairly assertive in arguments,” Saufley said before the session. “Students are sometimes surprised at the rapid give and take.”

The Mt. Blue appearance was the second high school court visit this week. Three oral arguments were heard Tuesday at Hermon High School, and three will be heard Thursday at Scarborough High School. The visits come at the invitation of state legislators such as Saviello.

“Tom Saviello has been persistent, and patient, and persistent again,” Saufley joked.

Saviello said that for rural schools such as Mt. Blue, the opportunity to have the court come to the students is indispensable, given that the students have limited access to Portland.

“You never know. One of these students receiving this message could be sitting on the bench one day,” Saviello said.

The structure of the proceedings was almost exactly the same as it would be in a normal courtroom, Saufley said. During the high school visits, students are presented with a brief contextual background before the oral arguments, and after each case the lawyers who presented their argument answered questions from students while the judges took a short recess.

Send questions/comments to the editors.