A record number of Maine high school students are getting college credit by taking college-level courses at their high school or a local college, in large part to cut the rising cost of a college degree.

Educators, students and their families, and politicians enthusiastically back these so-called “early college programs,” which are offered a number of different ways.

Some students go to a nearby college to take a class, with the state and college splitting the cost of tuition, while other students take college-approved courses at their own high schools after their teachers go through specialized training. Still other students are enrolled in smaller, highly organized, multi-year programs that result in seniors graduating with a full year of college credit at virtually no cost.

“It’s an incredible opportunity for high school students,” said Mercedes Pour, who oversees early college programs for the Maine Community College System. “I can’t think of a more powerful thing for a high school student to have.”

Some of the biggest enrollment gains in Maine are at the state’s community colleges, which have seen enrollment in early college programs jump 71 percent in the past five years, from 1,651 students in 2010-11 to 2,824 students in 2014-15.

At the same time, state spending for early college programs has more than doubled under Gov. Paul LePage to almost $1.4 million a year. LePage also backed the two-year Bridge Year Program, also known as a five-year high school because graduates earn a full year of college credit. That program is poised to double from 250 students this year to 500 students in 2015-16.

Enrollment in University of Maine System early college programs increased more than 20 percent in three years, from 1,400 students in 2013-14 to 1,700 students this fall.

Numerous studies have shown that high school students who take courses for college credit are more likely to enroll in college, less likely to need remedial courses or drop out, and are more likely to graduate in four years.

The rise in early college programs reflects a national trend, said Adam Lowe, executive director of the National Alliance of Concurrent Enrollment, which works with high schools to make sure the college-level courses they offer are rigorous enough. The alliance’s research found that the number of high school students taking early college courses is growing about 7 percent a year nationwide.

CUTTING COSTS, AVOIDING DEBT

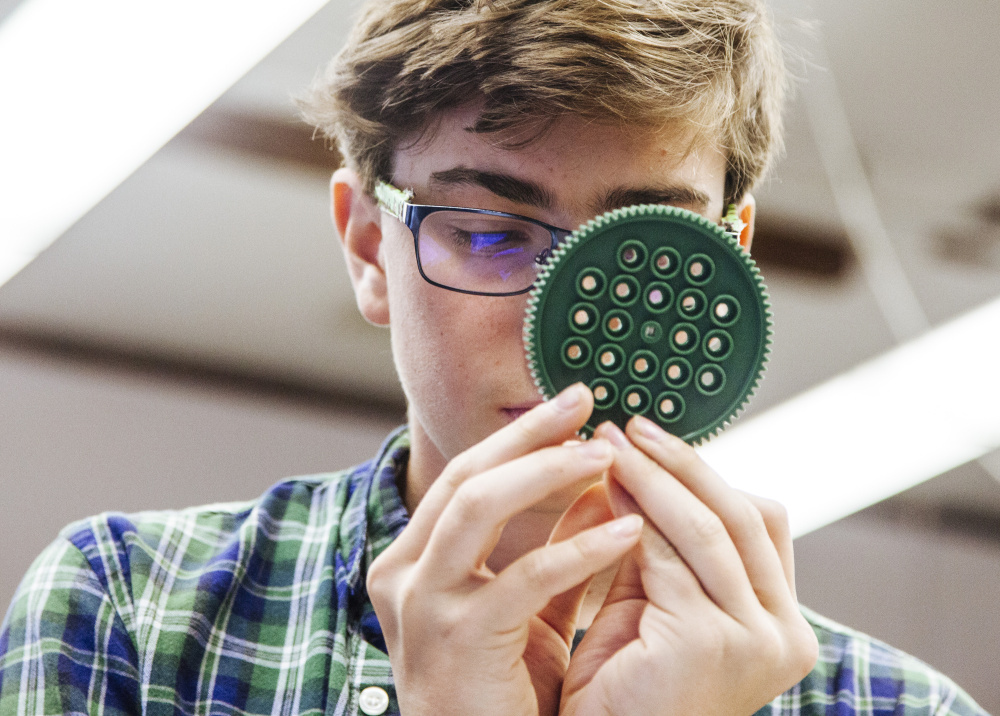

Sixteen-year-old Joseph Hughes is one of those students, taking an engineering course at Portland High School that will give him college credit if he scores high enough on the final exam.

One of 11 children, he’s already working three days a week washing dishes at Empire restaurant to help support his family. Getting college credit now – essentially for free – means that’s tuition money he won’t have to spend later. He also likes being able to try out different college courses in high school to figure out what he wants to study.

“There’s all these people with degrees but they don’t have a job, and they have all this debt. I want to avoid that,” said Hughes, who was figuring out gear ratio computations in the class. “It’s rough times.”

Angel Loredo, a higher education specialist at the Maine Department of Education, said early college programs make economic sense and are very popular.

In recent years, as concerns over student loan debt have grown, an increasing number of students are motivated to take as many of these courses as possible at the reduced or free rates offered to high school students. The average cost of a college degree is the highest it’s ever been, and student loan debt nationwide, at $1.3 trillion, has surpassed all other consumer debt aside from mortgages.

“Students are consumers, as are parents,” Loredo said. “They’re looking at this economically and asking, how can I get my kid through college without this huge debt?”

Pour and other educators say early college programs have long existed for gifted students or at private schools. They were previously aimed at “college prep” students and were mostly a way to keep seniors motivated before they went off to college.

But with more jobs requiring more than a high school education, the thinking evolved, and more colleges began offering free or reduced tuition to a broader range of high school students. While the programs grew, they still left out students who didn’t live near a college or couldn’t get transportation.

Now, many programs are delivered to a high school, using local teachers who go through specialized training and use specific college-approved curricula.

“Finally, we’re able to democratize this and bring it to all students, which is amazing,” Pour said.

Offering courses at the high schools is particularly important in rural states, said Lowe.

“If you want access, particularly in a rural state like Maine, you’ve got to bring it out to them in their high school,” Lowe said.

Most of the early college courses are general education classes such as English composition and math, but some students pursue specialized topics such as Latin, poetry, engineering, criminal justice or accounting.

Jane Ackerman, a Portland High School senior who wants to be a screenwriter, is taking Italian and cinema studies at the University of Southern Maine this semester. She doesn’t find the work too hard, but the attitude is different, she says.

“You’re not coddled at all,” said Ackerman, who is applying for early admission to Columbia University in New York. “It’s not their main priority that you are succeeding.”

Experts say that realization is important, since many freshmen can become overwhelmed when they suddenly face college work and are out on their own for the first time. Having a chance to experience college while still in high school makes for a “smoother transition,” Pour said.

STATE FUNDS THREE PROGRAMS

Despite tight state budgets during the recession, and pressure on education programs, early college funding got bipartisan support in the Maine Legislature. Task forces during both the Baldacci and LePage administrations looked at ways to expand early college.

Today, state money is used for three specific programs: The oldest, and largest at almost $675,000 a year, is Aspirations, a partnership between the state and the public universities and community colleges. Under the program, any high school student can take up to 12 credits a year on a college campus or online for free, with the state reimbursing the college for half the tuition cost and the college waiving the other half. Students pay book or course fees, depending on the college’s program.

University of Maine System Chancellor James Page said the program has been a huge success, even if the school is writing off tuition dollars during tight economic times.

“It’s the right thing to do,” Page said. “(The cost is) something we have to be mindful of, but the ability to develop those kinds of quality programs and make them accessible to high school students? It’s what we have to do. If we didn’t, it would be our priorities that were backwards.”

The relatively new Bridge Year Program, which receives $500,000 in state funds annually, allows high schoolers to graduate with up to 30 college credits – a full year toward an associate or bachelor’s degree. The first group of students, in a pilot program, graduated from Hermon High School in 2014.

Bridge Year creates a class, or cohort, of 15 to 20 students at specific high schools who stay together for all their high school courses and attend classes at a nearby career and technical education center. The students also have at least four internships during the two-year program, a dedicated guidance counselor, job training and college counseling, and access to the guidance counselor for a year after graduating.

This fall there are 250 students in the program at 14 high schools, and it is expected to double next year.

LePage said the Bridge Year Program has been a big success.

“Before I came into office, I said I wanted to see Maine offer its students a five-year high school opportunity,” he said in an email. “What we found was that Maine has a number of excellent programs that allow students to take college courses, but few complete packages like this, which will allow students to move seamlessly into a degree program. The Bridge Year initiative is a shining example of educators putting what is best for the student first and I commend everyone involved.”

NUDGING UNDECIDEDS TO COLLEGE

Founder Fred Woodman said Bridge Year has been successful “beyond my wildest dreams.” The program targets students who need the extra help to be successful, he said.

The state also allocates $215,600 a year for online Advanced Placement courses, which offer AP courses to students in rural locations where they may not have a local AP teacher at their school, or want to take an AP course that their school doesn’t offer.

All the programs, one teacher said, benefit everyone.

“It used to be there were kids who were going to college, or they weren’t going to college,” said 33-year teaching veteran Dan Deniso, who teaches a college-level statistics course at Portland High. The emphasis on early college experience can erase those categories.

“There’s not that big line in the sand. A lot of it is psychological,” he said. “It can provide the student with the sense that they can be a collegian.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.