For the last two years, Comcast has been testing a new pricing format on its Internet customers in Maine in a bid to drive more revenue and get consumers to pay for the data they use.

But the new pricing structure came as a rude surprise to Lyndsey Patton, a nurse from Topsham who is pursuing a graduate medical degree online.

A Comcast customer for five years, Patton wasn’t aware that Comcast was charging her overage fees if her family’s monthly data use exceeded 300 gigabytes, roughly equal to 100 hours of streaming HD movies. Last week she received an automated voice mail from the company saying she had exceeded her limit and would be charged an additional $10 for each 50 gigabytes of data used.

“It blindsided us,” said Patton, whose graduate program requires her to participate in online video classes for at least six hours a week.

Comcast said it informed its Maine customers of the cap in an email in November 2013, but many – like Patton – likely deleted or archived the message without reading it. The company is the first in Maine to explore what is becoming a national trend – billing customers for the volume of data they use rather than providing unlimited service for a flat fee.

The Patton family used 300 gigabytes in roughly the first half of its billing cycle. Patton chalks it up to her online classes, work her husband does on the Internet and the family, which includes a young daughter, streaming several hours of movies and kids shows on Netflix in an average day. She estimates she could be facing an additional $60 on her next bill if the second half of the month is anything like the first.

Disturbed that she’d be hit with the additional fees, Patton filed a complaint with the Federal Communications Commission last week. The policy is unethical, she says, because she never opted into it, and it creates an unfair burden on her as she tries to complete her degree to become a nurse practitioner. Comcast is her only viable option for high-speed Internet.

“If I can’t get to my educational media I’m going to lose out on thousands of dollars of education that my GI bill money is paying for … because I can’t get to the Internet without being nickel-and-dimed,” she said.

EVOLVING WITH THE TIMES

Comcast won’t reveal how many customers it has in Maine, but its footprint is small compared to Time Warner Cable and FairPoint Communications. It primarily offers service in the Freeport, Topsham and Brunswick areas, as well as in the York County towns of Kittery and Berwick.

Comcast started its use-based pricing plans in December 2013, according to Marc Goodman, a company spokesman. Maine is one of several markets around the country and the only state in the Northeast where Comcast is testing the new plans, he said.

It’s likely most Comcast customers in Maine are unaware of their 300-gigabyte cap because they never use that much data in a month. Nationally, Comcast customers’ median data usage is 40 gigabytes a month, Goodman said.

While Comcast has received complaints about the new pricing plan, Goodman said it makes sense for the heaviest users of the Internet to pay a greater share of the costs of maintaining the network.

“Usage is changing and we’ve always said we’d evolve,” Goodman said. “These usage-based trials are designed to be flexible and fair. Those who use the service more would pay for their share of their use, while those who use less, pay less.”

Comcast isn’t alone in advocating for tiered pricing. Eli Dourado, director of the Technology Policy Program at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, said usage-based pricing makes economic sense. First, using a tiered system creates lower-cost entry points for people who are not yet using the Internet.

“Standard economics would say a setup where some customers pay more and some pay less is more efficient and gets more people online,” he said.

Second, Dourado said usage-based pricing helps align the company’s interests with consumers who want faster Internet connections.

“Being able to charge consumers by the gigabyte of data creates a fairly strong incentive for companies to get network upgrades done quickly because they’re leaving money on the table if they don’t,” he said.

In other words, networks that allowed faster upload and download speeds would make it easier for customers to consume more data.

Based on that interpretation, Dourado said Maine might benefit from being a test market for Comcast.

“A test market for metered data might also mean you’re in a test market for faster service,” he said.

‘IT SEEMS ALL TOO FAMILIAR’

The U.S. Government Accountability Office published a report in November 2014 on Internet service providers adopting use-based pricing and what impact that would have on consumers. It found that seven of the 13 largest fixed-wire Internet providers now use it to some extent.

In its conclusion, the GAO recommended that the FCC work with Internet providers to develop a voluntary code of conduct to improve consumer communication and education, and also that the FCC should use existing data to monitor the adoption of data caps and track the impact on consumers.

Ryan Goodwin, a Comcast customer in Brunswick, recently became aware of the new pricing policy. A Web developer who works remotely, Goodwin uses about 150 gigabytes of data a month. He isn’t concerned about hitting the 300-gigabyte threshold now, but expects that his data use will increase as the Internet and data-heavy applications continue to expand.

“It seems all too familiar,” he said. “Like when you bought a computer and it had a 100-gigabyte disk in it and you never thought you’d use that amount of space, and then within a year or two your iTunes library went through the roof and suddenly you’re at the cap. Even though I’m only halfway there, I could see over next few years getting close to the cap.”

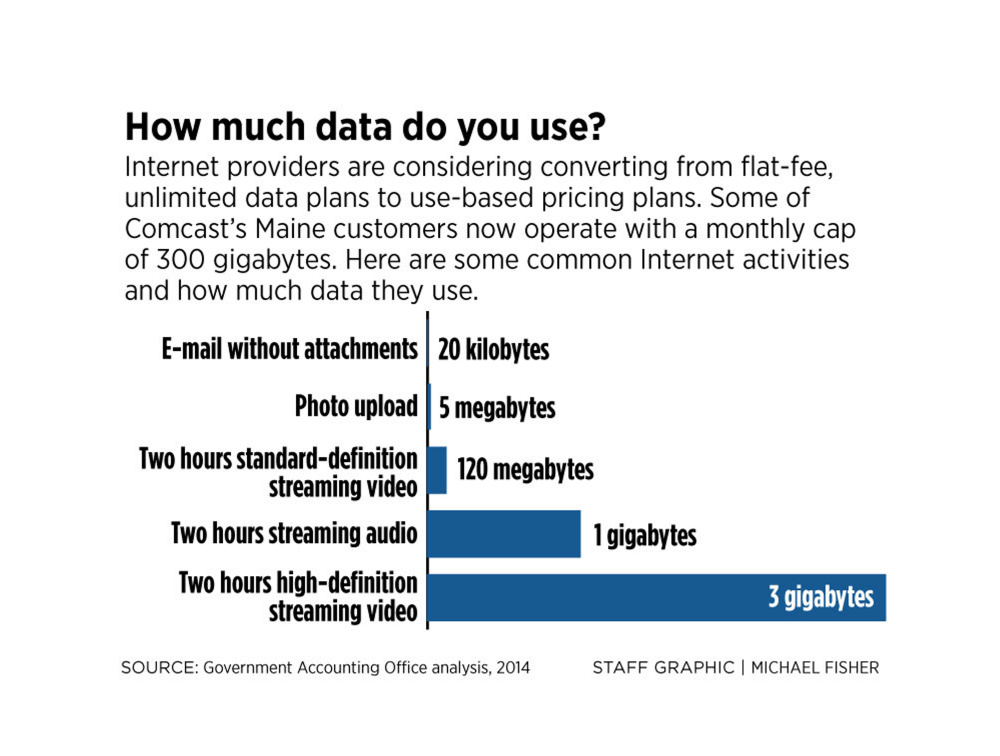

In its analysis, the GAO looked at common uses of broadband Internet and determined the average amount of data they consume. Sending an email without an attachment is about 20 kilobytes, which means a person would need to send 300 million emails in a month before hitting Comcast’s 300-gigabyte data allowance. Uploading a photo to Facebook consumes roughly 5 megabytes of bandwidth, which would be roughly 300,000 photos to hit the cap. The major data hog is streaming online video. Watching two hours of high-definition video on Netflix consumes roughly 3 gigabytes of data, according to the GAO analysis.

But the report notes that data usage is expected to continue increasing as people discover new Internet-based applications and existing ones become more refined. For instance, 4K video streaming, a format used by Netflix, can eat up as much as 8 gigabytes an hour, according to Consumer Reports.

Globally, fixed-wire data usage is expected to grow at an annual rate of 23 percent from 2014 to 2019, according to a report from Cisco. Using that rate, the GAO report concluded that the most data-heavy Internet users would be routinely hitting the 300 gigabyte cap by 2018, and easily tripling it by 2020.

Phil Lindley, director of ConnectME Authority, which is charged with expanding Internet access throughout Maine, believes Comcast is the only fixed-line Internet service provider in Maine using the use-based pricing plan.

“This person who used 300 gigabytes in 15 days, that would seem relatively unusual, but there are more and more applications that are big users of data,” he said.

Because of the consumer ire, companies are likely to continue rolling out the usage-based models slowly. If consumer outrage isn’t too high, Dourado believes usage-based pricing will become the norm.

“Bandwidth is cheap and it will get cheaper over time,” he said. “So I think for most consumers the right move here is just don’t worry about it.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.