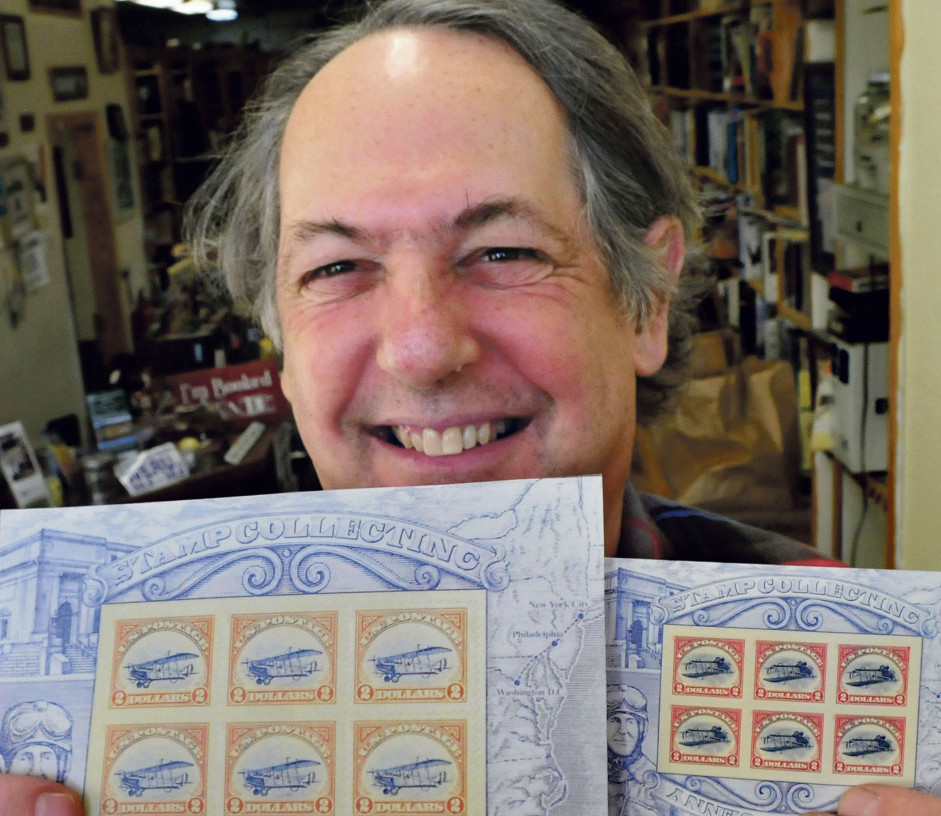

Waterville bookstore owner Robert Sezak doesn’t collect stamps, but his search for a rare upright Jenny was different.

Sezak regularly buys large-denomination stamps so he can ship online orders from his downtown bookstore. When he heard about the upright Jennys, he made it a point to try and get his hands on them.

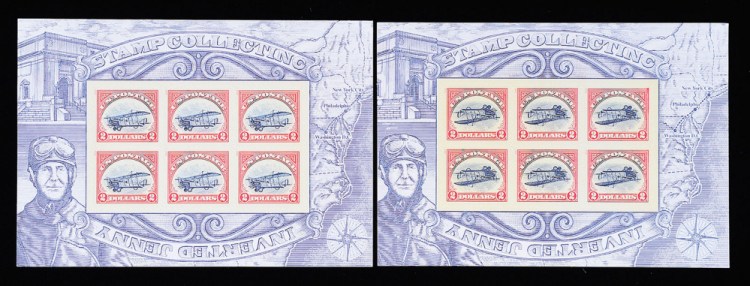

The regular red and blue stamps have an image of an upside down, or inverted, biplane — probably the most famous stamp printing error by the U.S. Postal Service. The rare special stamps show the plane right-side up. That “upright” or “corrected” Jenny is the difference between a $12 sheet of stamps and a collector’s item worth thousands of dollars.

“I was looking for them. I knew they were out there,” he said. “I figured, since I used the stamps anyway, I could casually seek them out.”

Two years ago, shortly after releasing a set of stamps in honor of the famous inverted Jenny mistake stamp from 1918, the U.S. Postal Service revealed it had concealed 100 limited edition six-sheet stamps in the 2.2 million, $2 stamps released to the general public. Since the stamps were introduced in 2013, less than a quarter of the rare upright Jennies have been found.

Sezak lucked out on those odds of one in 22,000. He found the 24th sheet at the Waterville Post Office in mid-September.

That sheet is now being held under lock and key at James D. Julia, Inc., an auction house in Fairfield. It will go up for auction Feb. 3-5, 2016, and is listed for between $40,000 and $60,000.

“I don’t collect stamps. I just thought it would be an interesting endeavor,” said Sezak, who is also chairman of the Fairfield Town Council.

The commemorative stamps come individually wrapped in a sealed envelope so customers couldn’t see if they were buying regular stamps or the special edition. The intent was “to recreate the excitement of finding an inverted Jenny when opening the envelope and to avoid the possibility of discovering a corrected Jenny prior to purchase,” the Postal Service said in a news release when it revealed the special edition. A congratulatory note comes with the special stamps, directing customers who find them to contact the Postal Service for a certificate of acknowledgment signed by the postmaster general.

Sezak said an announcement at the post office about the hidden special stamps piqued his interest, and he would sometimes buy all the Jenny stamps that were available. He doesn’t gamble or have much interest in contests, but since he had to buy stamps anyway, it seemed like it could be fun, Sezak said.

“It was something to do and I could do it,” he said. “I wouldn’t have done it if I didn’t have any use for the stamps. It’s not like I was spending money that wasn’t going to be used.”

Tony Griest, an assistant department head for fine art at James D. Julia, Inc., said the auction house doesn’t normally feature stamps and didn’t know about the upright Jenny until Sezak approached the auction house.

“It intrigued us from the standpoint of its rarity,” Griest said.

The set of six stamps for auction includes the congratulatory note found with the stamps and a certificate of authenticity from the Postmaster General.

But the upright Jenny scheme has sparked criticism, including from the Postal Service Office of Inspector General, the service’s watchdog agency.

In a management alert issued July 15, John Cihota, the deputy assistant inspector general, found that the Postal Service “strongly and inappropriately influenced the secondary market by creating the rarity,” adding that two sets of upright Jennies had sold for $51,750 and $55,000, respectively.

In his memo, Cihota found that the Postal Service hadn’t cleared the promotion with its legal department and confusion with its distribution plan meant that only one sheet of upright Jennies was sent out between March and December 2014. When staff at the stamp fulfillment center in Kansas discovered the mistake last December, they randomly selected three customers who ordered the inverted Jenny commemorative stamps and sent them an additional sheet of upright Jennies in violation of Postal Service policy that prohibits employees from giving away stamps, according to Cihota’s report.

In conclusion, the inspector general’s office determined that the Postal Service needed to improve controls, but agreed with Postal Service management that it would not be cost-effective to locate the stamps in the general public and would be bad business practice to destroy them. Meanwhile, 23 of the stamp sheets still have not been distributed.

In 1918, the post office issued its first 24-cent airmail stamp, marked with a red and blue design featuring the image of a Curtiss JN-4H biplane, otherwise known as the Jenny. In a rush to celebrate the first airmail flight with the stamp, 2.2 million of the stamps were printed with a sheet of 100 stamps printed incorrectly with the aircraft upside down making it into general circulation.

That sheet of inverted Jennies was bought by a 29-year-old cashier from Washington, D.C., named William T. Robey shortly after the airmail stamp was released. Robey flipped his purchase to a Philadelphia stamp dealer a week later for $15,000, according to the Postal Service.

Since then, the inverted Jenny has become one of the most sought-after and alluring stamps in U.S. history. In 2007, a single inverted Jenny sold for $825,000 at Heritage Auction Galleries, in Dallas, Texas, and in 2005 a block of four stamps was valued at $2.97 million, according to the Robert Siegal Auction Galleries in New York City.

Peter McGuire — 861-9239

Send questions/comments to the editors.