A significant decline in a problem as serious as homelessness should be something to celebrate. So we are encouraged by the findings of a national study that shows a 13 percent drop in Maine’s homeless population, from 2,726 people to 2,372, between a night in January 2014 and another night a year later.

But it’s far too soon to declare victory.

Short-term fluctuations don’t tell the whole story. Over time, Maine’s homelessness problem has not been getting better. Additionally, cuts to state aid for Maine’s largest shelter in Portland put pressure on services last winter, and that is likely to happen again this year.

And the decreased availability of low-income health care, including mental health and substance abuse treatment, means that some of the root causes of chronic homelessness are not being fully addressed.

The rosy report on Maine was included in the 2015 annual Homelessness Assessment Report to Congress, released last week by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development.

It was based on the “point in time” surveys conducted each January, which attempt to count all the sheltered and unsheltered people in every community. It’s an imprecise method, and the numbers tend to fluctuate from year to year, but the trends are more trustworthy.

The 2015 report showed a 13 percent drop for Maine, compared to a 2 percent drop nationally. But over five years, Maine’s homeless population has stayed flat, while the national number declined by 11 percent.

The number of homeless people should drop when the economy improves, but that does not seem to be happening in Maine in the seventh year of economic expansion. It’s troubling to wonder what will happened when the next inevitable recession hits.

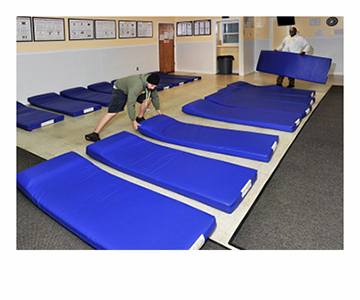

Even with less demand, conflict between the state and an important service provider raise questions about whether Maine will be able to meet the demand. There was a crisis last winter precipitated by the LePage administration’s decision to end a 30-year-old understanding with the city of Portland over the funding of the state’s only municipal homeless shelter, which typically houses more than 25 percent of the state’s homeless population.

Faced with the loss of $850,000 in state funding, the city shifted costs onto local taxpayers, even though shelter clients come from all over Maine. That same crisis is likely to recur this winter, and there will be pressure on elected officials in Portland to cut services.

While other states have been expanding Medicaid, which provides health care to people with low incomes, Maine has been shrinking its program. The LePage administration not only blocked the acceptance of federal funds to pay for low-income health care but also excluded from the program thousands of childless adults who had been previously eligible.

The loss of federal funds has resulted in layoffs and budget cutting at Maine hospitals, including the decision by Mercy Hospital to shut down its substance abuse clinic. The loss of drug treatment opportunities almost certainly will result in more ambulance calls, more police interactions and more nights in jail. It also likely will result in more nights in the state’s shelters.

So while a one-year decline in the homeless count may be better than an increase, it doesn’t mean the worst is over. Somewhere around 2,300 men, women and children in Maine have no place to live, and winter is just a few weeks away.

Send questions/comments to the editors.