Special education students enroll in Maine’s charter schools at a rate that is twice the national average.

Maine’s experience runs counter to the argument that charter schools intentionally underenroll these high-cost, high-needs students with an eye to lowering costs and, perhaps, improving overall academic performance – critical factors in attracting future students and donors.

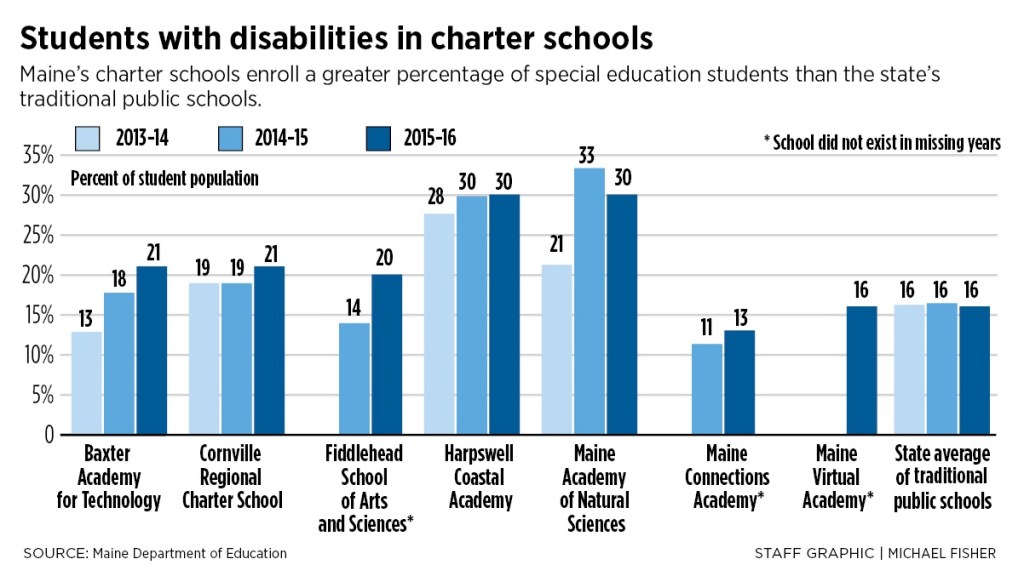

Twenty percent of enrollment in Maine’s charter schools consists of students listed as special education – those with disabilities ranging from ADHD to severe physical or intellectual disabilities – compared to a 10 percent average nationwide and 16 percent at Maine’s traditional public schools.

The higher-than-expected number surprised Maine Charter School Commission member Jana Lapoint.

When the first two charter schools in Maine opened in the fall of 2012, she said, state officials expected special education enrollment to be about the same as the statewide average.

Instead, the state’s five brick-and-mortar charter schools have seen rates between 20 and 30 percent today, according to data from the Maine Department of Education. The state’s two virtual charter schools are at 16 percent and 13 percent.

“When we were seeing this, we said, ‘Whoa! This is a surprise,’ ” Lapoint said.

There’s no clear reason for the trend: None of Maine’s seven charters is geared toward students with special needs, and the schools haven’t been open long enough for operators to have a good sense of what’s affecting enrollment trends.

“I suspect that all the charter schools are seeing, as we are, kids from a variety of backgrounds and with a variety of strengths and skills, looking for schools that will play to those strengths,” said Michele LaForge, the head of school at Baxter Academy of Technology and Science in Portland, where the special education population is 22 percent.

“One thing I know is that a strong classroom, with a diversity of instructional and assessment methods, is an intervention, and it improves opportunity for learning for everyone, special ed or not. When a whole school is built around providing this diversity in instruction and assessment, it’s good for everyone, not just special ed students.”

‘IT FELT LIKE FAMILY TO ME’

Parents and charter school advocates in Maine say there are several likely reasons that families with special ed students are attracted to Maine’s charter schools: The schools are new, offering a fresh start for a challenged student; they are small and are more likely to offer individual attention to each student; and they offer nontraditional learning environments.

“It was a miracle. It was like night and day,” said Mary Hodges of Albion, who enrolled her granddaughter Tanika Hodges at Maine Academy of Natural Sciences (MeANS) after the girl started struggling at Lawrence Junior High School in Fairfield. Despite a one-on-one aide for an attachment disorder, Tanika was getting into trouble and floundering academically.

“We were called in at least once a week to come get her,” Hodges said. “It was just a nightmare for her grandfather and myself.”

But Tanika flourished at MeANS, a charter school with a hands-on natural sciences curriculum in Hinckley.

“There were smaller classes, it was more hands-on (learning), you could go outside and get experiences. Plus, all the other classmates were there and they could help you,” said Tanika, who graduated from the school in the spring. “It felt like family, pretty much, to me.”

“If I had stayed at Lawrence (High School), I probably would have dropped out,” she said. “It was pretty much horrible.”

The Maine Charter School Commission has also been careful to learn from other states’ mistakes, trying to avoid the controversies that have plagued the nationwide charter movement. Where other states have been criticized for a lack of oversight, the Maine Charter Commission conducts exhaustive reviews before approving a school, and regular follow-up, on-site visits. Where virtual schools were criticized for having too much control over charter schools in some states, the commission included specific language in contracts requiring more local control and oversight for virtual charter schools.

In the same way, the commissioners have grilled charter school applicants about their ability to recruit widely, include all student groups, and adequately handle special education populations. In other states, charters have been accused of subtly discouraging these students from applying, or “counseling out” special ed students by telling families that the school isn’t a good fit for the child.

“That’s certainly not the practice in Maine,” said Roger Brainerd, executive director of the Maine Association for Charter Schools. “Our law is very prescriptive about taking every child. We’re serious about that.”

WHAT IS SPECIAL EDUCATION?

Under federal law, all public schools must provide “free, appropriate” education to students with disabilities, which can range from mild dyslexia or a disorder such as ADHD, to profound physical or intellectual disabilities.

All special education students have an individualized education program – or IEP – that spells out exactly what the child needs, how the school will deliver that service, whether it be occasional tutoring or a one-on-one aide that accompanies the child all the time, and sets measurable goals that are regularly evaluated.

Nationwide, special education students make up 10 percent of enrollment in charter schools, compared to 13 percent at traditional schools, according to an October report by the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools that analyzed federal education data from 2011-12, the most recent data available. The report found that only four states – Virginia, Iowa, Maryland and Ohio – have more special education students in their charter schools than in their traditional public schools.

Special education services cost money, and there is a complex funding formula that provides federal, state and local aid to public schools for their special education populations, but it does not cover all costs.

Under Maine’s funding formula, the state provides a set amount of per-student funding – different in each district – and provides an extra 15 percent for special education students. If costs exceed that amount, the district must pay until its expenses are more than three times the original amount, triggering additional state funds.

While burdensome for any cash-strapped school, it is particularly threatening for charter schools, which are not able to draw on local taxpayer funds the way traditional school districts do.

Commission members note that Maine’s charter schools create IEPs – or something like it – for every student, explaining that all children deserve to have a close evaluation of their needs whether or not they are identified as special education students.

That can also remove the perceived stigma of having an IEP, educators say. Special education students, if they are self-conscious about the label, may feel more comfortable in an environment where every student is individually profiled.

“Until you actually deal with a situation personally, it’s hard to understand,” said Brainerd, who has children and grandchildren with special needs. “You want them to have maximum opportunities. I think anybody with a child wants the best for their child and looks for other options, and charter schools are certainly an option to consider.”

It could also be as simple as a fresh start or a new school atmosphere.

“If I was that mom looking for a school for my (special education) child and felt there were too many kids or he wasn’t getting the attention he needed – or whatever it is that just isn’t working – then I may have hope that a whole new different learning environment will make a difference,” commission Chairwoman Shelley Reed said.

“Charter schools are creating interesting school environments, and so that charter school might be attractive,” Reed said, citing the recently approved Snow Pond Arts Academy, which will offer daily music instruction. MeANS and Harpswell Coastal Academy have hands-on environmental programs where students are frequently outside, incorporating school lessons into outdoor activities.

A MATTER OF THRIVING

Virtual schools are different, Reed said, because they require each child to have an at-home learning coach, usually a parent, who works closely with the child.

Maine Virtual Academy has 16 percent special education students – the same as the state average – and Maine Connections Academy has 13 percent.

“That special ed kid might need more support than that parent can give,” Reed said.

Reed said word-of-mouth might lead to the charter schools seeing even more applications from special education students. Most of the schools use a lottery system for enrollment.

“Next year, I wouldn’t be surprised to see more special education kids attending charter schools,” Reed said. Families already in the system will tell others: “I’m going to tell another parent, ‘Hey – try this.'”

State special education specialists agree that close, personalized attention makes a difference in any environment.

Charter schools “really, really own their kids and are trying very hard to meet their needs,” said Jan Breton, state director of special services.

Leanne Moll said switching from a public school to MeANS has made a profound difference for her son, Hannes, who is a junior. A memory processing problem meant Hannes was spending two and three hours a night on homework at his old school.

“I thought this is crazy, this isn’t serving him. I’ve got to do something different,” said Moll, a literacy specialist at RSU 18.

That’s not uncommon for many families who consider MeANS, said Emanuel Pariser, director of instruction.

“We do have a lot of students whose parents felt they weren’t thriving in traditional schools,” Pariser said. “Some were flunking out, not behaving well, some weren’t challenged or their interests weren’t being met. They were being passed over in a much larger system that couldn’t get a handle on what these students were interested in.”

REFERRED BY TRADITIONAL SCHOOLS?

Moll said the focus on the outdoors and ability to encourage Hannes’ natural inclination to pursue a trade eventually has worked.

“They were willing to accommodate him. They really bent over backward,” she said, adding that the school “paid attention to his natural talents.”

“He used to be a little more quiet, and he’s so much more self-confident,” Moll said. “The school has done a really good job in recognizing and praising him for qualities like being responsible and being a good citizen.”

Charter school operators say they also think traditional schools are referring students to the schools.

“I do think that’s a significant factor,” said John D’Anieri, director of Harpswell Coastal Academy, which has 30 percent special education enrollment. “Professional staff in other schools are recommending Coastal Academy to families.”

Coastal Academy also has the other factors people cite as attractive to special education families: the school is small, focuses on close student-teacher relationships, offers individualized plans for all students and has vigorous anti-bullying programs, D’Anieri said. Those traits can attract a range of students.

“Parents who have had kids who struggled in school maybe are more willing to try something new,” he said. “There may be a greater appetite among folks whose kids have special needs for a different kind of school.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.