When an artist lives as long as Ellsworth Kelly, who died Sunday at age 92, it can be difficult to recapture what made that person’s work bracing when it was new. And when an artist is as successful as Kelly was, when his work becomes canonical and essential to any synoptic survey of art history, it is difficult to see it independently of its fame, reputation and ubiquity.

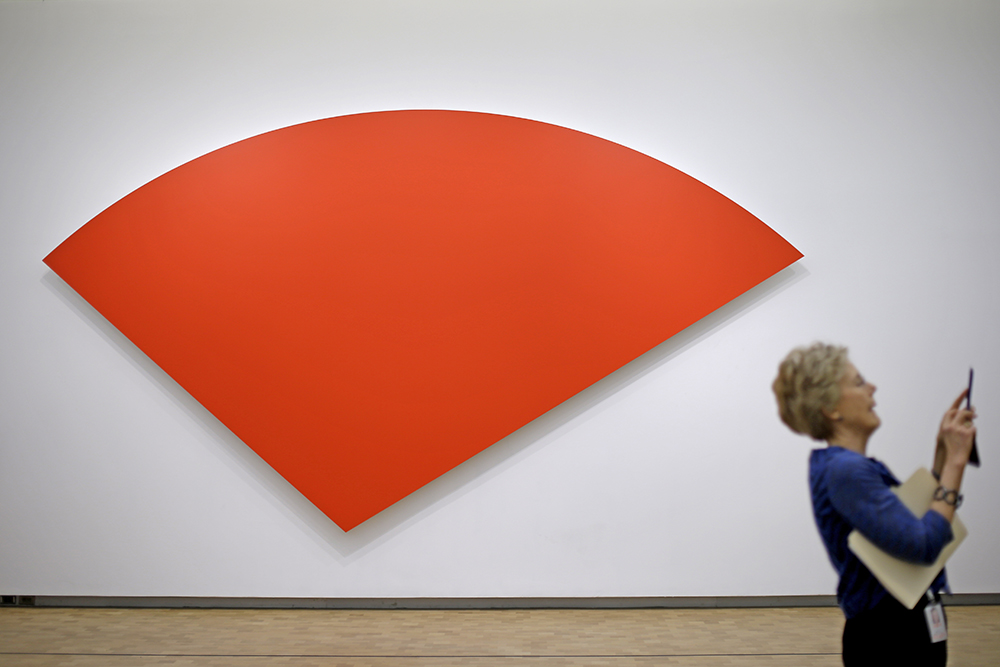

The seeming simplicity of Kelly’s style – his use of single panels of bright color – also made it both easy to take in at a glance and easy to underestimate. It was paradoxically both “simple” and “hard” at the same time, appealing and instantly recognizable, yet also strikingly difficult to penetrate and comprehend.

In his later years, when he was as famous as an artist can be, and when no contemporary art collection was complete without something by Kelly in it, his work often seemed to be closed up and silent, colorful coffins meant to foil any effort at explication or interpretation.

But his earlier work was more open, more interesting and more rewarding. In 2013, the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia displayed an early piece, from 1956-1957, made around the time that Kelly was first attracting notice from critics and gallerists in New York, and his first pieces were being accessioned by important museums.

“Sculpture for a Large Wall” consisted of 104 anodized aluminum panels, colored red, blue, yellow and black, and laid out on four long rows measuring 65 feet. Each panel seemed different from the next, subtle variations on the parallelogram, and yet together they also suggested a kind of language, or code, as if their shapes, colors and repeating patterns spelled out a basic computer language, or proto-digital message.

The space in between the panels, and the shadows they cast on the wall, were also part of the effect, creating a contrast between the material substance of the art, and the cascading visual and mental ideas it conveyed. The piece was playful, and serious; present and absent; material and imaginary; visually bold and intellectually diaphanous.

Often, with Kelly, you felt as if he offered up some ideal slice of the world, decontextualized almost to the point of absurdity. A single arc sliced out of a circle; a single perfect rectangle; one bold juxtaposition of color or shape. But when he allowed his work to encompass more complexity, to indulge a rhetoric of repetition, rhythmic contrasts, and multiple self-replicating ideas, it began to feel like language, or narrative. And this was always his best mode.

It’s easy to forget, of course, that he came of age as an artist when the limitations of the abstract expressionists – the ego, the indulgence, the masculine hypertrophy – were increasingly apparent to younger artists looking for a different direction. For Kelly, art and self-denial became intertwined; the subjective impulse, the need for personal expression, wasn’t what drove him. When the Barnes Collection showed “Sculpture for a Large Wall,” it was in a gallery apart from the main exhibitions rooms, full to bursting with late 19th and early 20th century work that scream subjectivity and embody the last of the romantic artistic ideal of self-expression and dramatization. Kelly’s work, in that context, looked like an exercise in Zen.

And he lived long enough for his work to perform more than one revolution. His work of the 1950s and ’60s would have a powerful impact on the development of minimalism, and his work was still adroitly in dialogue in the larger art world when he died. Now the message wasn’t one of pioneering reduction and distillation, but of serenity and dignity. He remained to the end a resolutely independent artist, and never wavered from his vision of colorful austerity, producing art that was resistant, yet never trivial, always clean, bold and deceptively simple.

Send questions/comments to the editors.