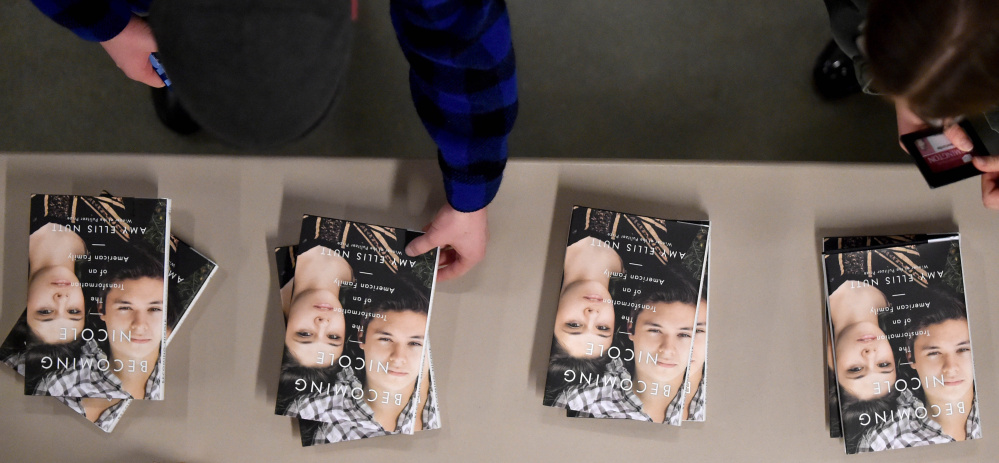

FARMINGTON — Jonas Maines didn’t make it through the first page of the prologue of “Becoming Nicole,” which chronicles the transformation of his family as they accepted, supported and fought for his identical twin as she grew up transgender in Maine.

But Maines, a freshman at the University of Maine at Farmington, said when he began reading the book by Amy Ellis Nutt, he had a flashback to himself and his sister at age 2.

Nicole, at that age known by her birth name, Wyatt, was watching her reflection in their stove’s glass as she danced in a dress and their father was videotaping.

Maines remembers his father asking, “Wyatt, show them your muscles.” When his sister didn’t comply and continued dancing, Maines said his father asked again, this time in a more serious voice. Still she danced.

“What it came down to was, ‘Wyatt, stop being yourself,'” Jonas Maines told a packed audience Thursday at UMF’s Emery Center. At that point in the flashback, Maines said he “threw the book across the room, and I haven’t picked it up since.”

That is one of a few stories from his and his sister’s childhood that Maines told classmates Thursday night at a discussion titled “Transforming Perspectives: Two Generations on Gender.”

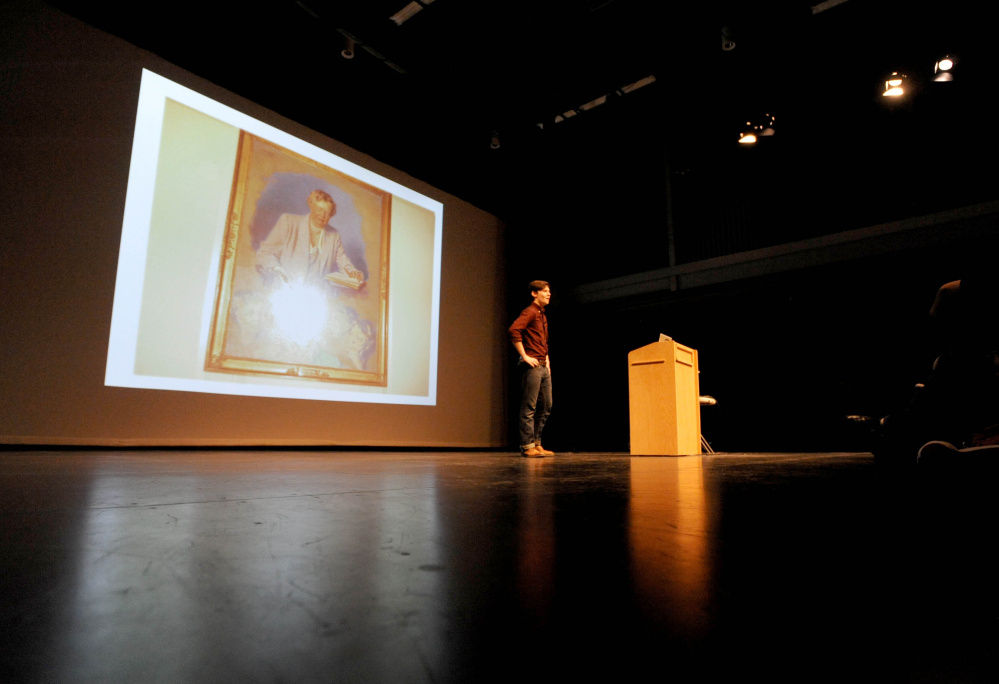

The discussion, hosted by Maines and his father, drew an audience that filled the Performing Space at the Emery Community Center for the Arts on UMF’s campus.

Wayne Maines started the talk by outlining his family’s story, explaining how he had to address his own personal conflicts of why he was afraid that Nicole, from a young age, identified as female. He explained the scrutiny his family faced as his daughter became the poster child for transgender youth in Maine and nationwide, ultimately winning a landmark court case allowing transgender individuals to use the bathroom of whatever gender they identify with, only after his daughter was forced to use a staff bathroom as a fifth-grader in the Orono school system.

He detailed the struggle he and his wife went through as parents who told their children to be themselves, only to have society tell their daughter that being herself was wrong.

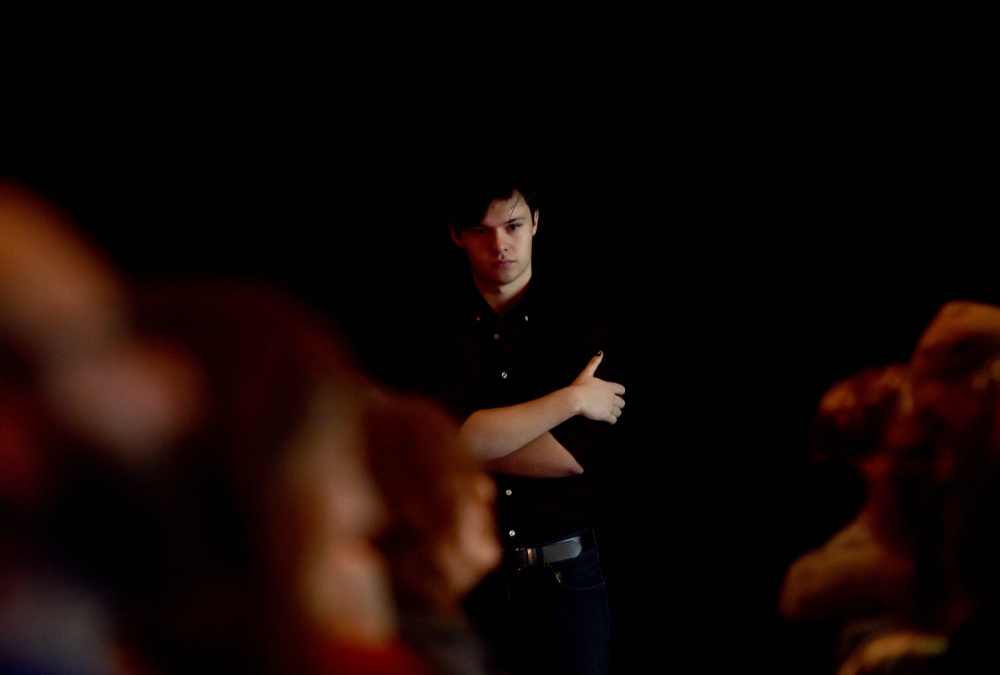

But when Jonas Maines stepped up to tell his story Thursday, he didn’t want to dwell on the hardships; those were tough enough to live through the first time. And anyway, he said, that wasn’t his story; it was his sister’s. Instead, his story was one of support, of being the brother at school who had to look out for and protect his sister.

“I was there, and I saw all this stuff happening,” Jonas Maines said. “And I thought, how can we make it so no other kid has to go through that?”

His message for his classmates was one of looking forward, of addressing how we as a society can stop making transgender youths go through the torment his sister endured from classmates — and what’s worse, he said, adults.

He presented two ideas: Teach children acceptance and tear down the wall of difference that society places around transgender people.

After watching his sister be exiled from her friends in fifth grade because a classmate called her a derogatory term for homosexual, Maines said he realized the effect that adults have on children and how those children treat other individuals.

“Looking back on it, it wasn’t the kids. Those weren’t their thoughts,” Maines said. “These ideas of prejudice, ignorance (and) bigotry came from an adult who was supposed to support and guide children, not teach them hate.”

Maines asked how many people in the room were planning to become teachers. About a third of the students in the room raised their hands. He encouraged them to teach their future students acceptance and to set an example instead of being passive, as he said so many teachers around his sister were.

“Bigotry isn’t instinctive, it’s learned,” Maines said. “You guys are going to be really important, so please don’t mess it up.”

He also encouraged his peers to stop placing transgender people outside of the circle of normalcy, because that classification as “not normal” affects a child throughout life. He said that was reflected in how he and his sister adjusted differently after high school.

“Growing up, I didn’t have to use a special bathroom. … No one denied me my basic rights as a person,” Maines said. “So much of a child’s development happens at school. So much of them becoming who they are as adults can be traced back to their (time in) school.”

“Everything that happened, that impacted (Nicole).”

Maines said he was nervous about discussing his family’s story with his classmates, since such a large part of his college experience thus far has been about discovering who he is without his sister. Nicole is in Orono, at the University of Maine.

“(In college) it was no longer Nicole and Jonas or Jonas and Nicole,” he said. “It really gave me a chance to develop who I was.”

Christina Hallowell, a senior at UMF, met Maines through the theater program, but Thursday’s discussion was the first time she has heard him talk about his family’s story.

“I’ve never talked to him about it before, so it was cool to hear him say it very eloquently,” Hallowell said.

Another friend, Tucker Atwood, said after the presentation that, as a secondary education major, he hopes he can teach the principles he’s learned from the Maineses’ story.

“You’re trying to teach them all the same thing, but they’re all different,” Atwood said. “So you have to realize what is going on in these students’ lives in order to use that when you teach.

“You can’t just teach them all the same way and assume everything is happening to them the same way.”

Lauren Abbate — 861-9252

Twitter: @Lauren_M_Abbate

Send questions/comments to the editors.