After 12 years of working at the Androscoggin Mill in Jay, waking up at 4 a.m. every day and driving 40 miles to the mill, Doug Mathieu walked out the security gate for the last time on a November evening.

His wife, Sarah, greeted him with a kiss when he pulled into their driveway in Anson; and the couple’s two black pugs, BB and JJ, ran around his feet. There was homemade chili and apple crisp for dinner.

A dry-erase board in the background had a to-do list with one item on it: “Check on job.”

With his cheery disposition and love of music — Mathieu is a guitar and mandolin player who takes pride in playing at community events — he does a good job of hiding any nervousness or fear after he was laid off at the mill.

“When I had a chance to go to the paper mill, I said, ‘That seems like a good job. I think I’ll take that,’ and I thought I would be there for the rest of my life,” Mathieu said. “It’s a scary thing being let go at 58.”

The Mathieus were prepared to make small cuts to their household budget — eating leftovers instead of going out for pizza, and getting rid of specialty cable channels. They were grateful not to have a mortgage or car payments.

“I was scared and my wife said I was a little depressed. I think it’s the uncertainty of not knowing what your future’s going to be,” Mathieu said. But the day after his last day at the mill, Mathieu started looking for a job and dropping off resumes at area businesses. He got a call back the day after that with a job offer from Cousineau Wood Products in Anson, which makes wooden bleacher seats and gunstocks.

“Physically I was only out of work for one day,” Mathieu said proudly. He attributes his success to a positive attitude.

Not every laid-off millworker is as lucky as Mathieu.

After four paper mills around the state closed in the last two years and layoffs at others, hundreds of people still are looking for work or getting the training they need to start a new job.

A fifth mill, Madison Paper Industries, announced last week that it will close in May, putting 214 people out of work.

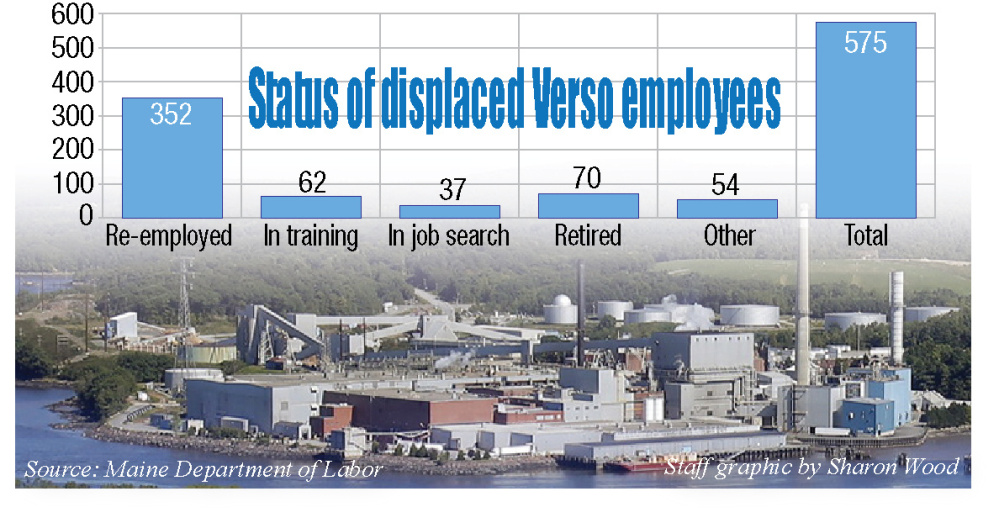

Of the more than 1,300 millworkers laid off at Verso Corp.’s Bucksport mill, Great Northern Paper in Millinocket, Lincoln Paper and Tissue and Expera Specialty Solutions in Old Town, 719 had been re-employed as of November, according to the Maine Department of Labor. Layoffs at those mills took place in 2014 and 2015.

Along with other layoffs, the paper industry — once the heart of Maine’s manufacturing sector — has suffered a loss of more than 6,000 jobs in the last 15 years, according to the department.

What those workers do, where they go and how easy it is for them to find new employment are dependent on a variety of factors, according to experts; and while the number of paper industry jobs is shrinking, some workers and employees of local career centers said they have hope that workers, with the help of some key federal and state resources, can find a place to go.

CHALLENGES FOR WORKERS

Geography, worker demographics and the emotional toll of losing one’s job are some of the challenges facing displaced workers as they try to re-enter the workforce, according to Ed Upham, manager of the Tri-County CareerCenter in Bangor. The center has worked with millworkers from GNP, Lincoln, Verso and Old Town in recent years.

“It’s a challenge for people to find jobs and train for them if they live someplace like Millinocket, East Millinocket or even Lincoln,” Upham said. “If they want to train for something, they have to be open to travel or relocation.”

Once workers make that decision, Upham said, there are lots of opportunities available, including in heating, ventilation and air conditioning; woodworking; truck driving; and the medical field.

Maine, with a median age of 44, has the oldest population in the country, according to the state Department of Labor, and that presents another challenge.

“The biggest challenge is the demographic of the folks we’ve worked with. They’re seasoned workers, they’re older workers, and a lot of them weren’t that excited to be going back to school and taking classes,” Upham said.

Mathieu, who has thinning gray hair that he often covers with a baseball cap, said he dropped off resumes only to be turned away by employers who “saw the snow on the roof.”

“I checked with a couple of different places and I was getting the feeling that because I’m 58 years old, they didn’t want anything to do with someone close to retirement age,” he said.

There’s also the challenge of overcoming the psychological aspect of losing a job, the grieving and sense of loss that Upham said can be similar to losing a loved one.

“They may blame themselves, or they blame others and are depressed. A lot of people go through that process, and for some it’s easier than others,” he said.

There’s no timeline for when workers will have adjusted to their new lives.

A number of factors — deciding what they want to do, whether they need to go through training or not, whether they are willing to relocate, what type of assistance is available to them — can all influence how long it takes for someone to get back into the job market.

There are fewer jobs left in the paper industry, but Upham and others said they think there are enough jobs in Maine for laid-off workers.

Officials from Sappi Fine Paper in Skowhegan, one of the state’s eight remaining paper mills, have met with officials at Madison Paper about hiring workers from the Madison plant, according to Kelsey Goldsmith, a spokeswoman for the Maine Pulp and Paper Association. “I think that will be the case at other mills too. There are a couple nearby that can help make the transition easier.”

Paper mill jobs are some of the highest-paid manufacturing jobs in Maine, with workers earning about $70,000 annually on average, according to the Department of Labor. Those salaries can be hard to match in other industries, Goldsmith said, even while workers at the mills may have the skills to do other work.

“When people think of millworkers, they think of people making paper; but there are also people who work in the offices, in human resources, in accounting,” Upham said. “What I’ve found working with these millworkers is they have a host of skills. They’re very good with their hands. Half of them can weld already. They just don’t have the certification, so we can help them do that in eight or six months and they can then go out and get a job.”

At the Androscoggin Mill, Mathieu made $23.68 per hour; at his new job, he makes about half that. Through the federal Trade Adjustment Assistance program, a federal program that helps provide resources and education for workers whose jobs have been hurt by foreign trade, he is able to earn half the difference in the two salaries, up to $10,000 or for up to two years. It’s still less then what he used to make, but Mathieu said it will get him by until retirement.

GOING BACK TO SCHOOL

Of the 1,300 workers left jobless from the four recently closed mills, about 200 are in training or pursuing job training for a different job, according to the latest figures from the Department of Labor.

Cindy Naaykens, a former paper tester at the Androscoggin Mill, is one worker who decided to go back to school to study business management and computer systems integration after getting her layoff notice at the mill last year — her second such notice after she was laid off at G.H. Bass & Co. in Wilton several years before.

She took the mill job about 14 years ago because the pay was enough to support herself and her children; and because it was with a large company, Naaykens thought there would be room for advancement.

“Going to college was something I always had as a goal, but when I started out, I made choices in life like having children, and I wasn’t able to,” said Naaykens, who turns 50 this month and is in her first semester of a two-year program at Kennebec Valley Community College. “I’ve always wanted to go to college, and I said, ‘I can do it. This is the time.'”

Getting ready to start classes in January after her December layoff wasn’t easy for Naaykens, who said she took advantage of KVCC’s Admit in a Day program, which waives application and placement test fees for prospective students who commit to the school at the one-day event.

The TAA program also has been of use to her, paying her tuition and reimbursing her for books and supplies. The two unions at Madison paper filed a request that the program be implemented for Madison workers. Three members of Maine’s congressional delegation — Republican Sen. Susan Collins, independent Sen. Angus King and U.S. Rep. Bruce Poliquin, R-2nd District, announced Friday that they filed a letter of support for the petition with the U.S. Department of Labor.

Naaykens figures she has about 17 years left to work, and she wants to spend it doing something she enjoys. She’s upbeat about the prospects of finding an office job in central Maine where she can work in IT.

“We can’t change the fact that we’re going to lose our jobs,” she said. “You can either accept it and get on your feet running and succeed at what you want, or miss out on opportunities because you’re depressed about it. Even though it’s kind of sad or depressing that you’re losing your job, you have to say, ‘There’s nothing I can do to change that, but I can change the outcome.'”

Several dozen laid-off workers from the four mills that closed in the last two years also have enrolled in training programs or classes at Eastern Maine Community College or the Northern Penobscot Technical Center.

As mills in East Millinocket, Lincoln and Bucksport all closed within a short time span, EMCC has worked with many displaced workers trying to go back to school, said Director of Public Relations, Marketing, Business and Industry Matthew McLaughlin.

The school, with the Department of Labor, set up the two specialized programs for former millworkers, one in heating ventilation and air conditioning technology and one in fine woodworking and carpentry. Millworkers can use the TAA program, the same one used by Naaykens, to pay for their tuition and expenses.

The programs at EMCC were designed to place workers in fields that have high demand, available jobs and good wages and benefits, according to McLaughlin. Of 12 students who finished the woodworking program in July, only one student has not found employment, he said.

Heating, ventilation and air conditioning has also been a popular course for workers from the Androscoggin Mill in Jay who have worked with the Maine CareerCenter in Wilton, according to Bruce Stevens, a peer support worker at the career center who himself was laid off from the Jay mill last year.

Stevens is one of two former millworkers who were hired at the career center as peer support workers, a temporary job that provides support for other workers as they look for new jobs or consider what they will do next.

Stevens, 63, took early retirement and plans to retire on that money and Social Security after he finishes the temporary job.

Stevens, who worked at the mill for 38 years, said the layoffs last August were not something he expected.

“The career centers have a lot of good resources that will help people out, whether they want to get training or go look for work,” he said. “I think they have ways of helping people that they maybe didn’t know about before. I never thought about it before, because I didn’t need the help, and I think that’s the same boat a lot of people from Madison are in.”

Naaykens, who used the CareerCenter to enroll in the TAA program and answer other questions about her transition to college, also said she thinks that for many workers, the process of going through a layoff is unfamiliar and they might not be aware of what resources are there to help.

“The initial information they gave us in Rapid Response (the state economic program) meetings was what allowed me to make all this happen,” she said, “along with my own determination.”

Rachel Ohm — 612-2368

Twitter: @rachel_ohm

Send questions/comments to the editors.