WAYNE — Watching things leave and return to earth was a regular part of Rosanne Graef’s childhood. Her father, Howard Holman, was a commercial pilot who enjoyed flying smaller planes in his free time and built an airstrip on their 90-acre property overlooking Androscoggin Lake.

Holman is now deceased, but his daughter has ensured his celestial wanderings won’t be forgotten. Five solar panels now sit on a quarter acre of land next to that unused airstrip, grazing on the sunshine through which Holman once flew.

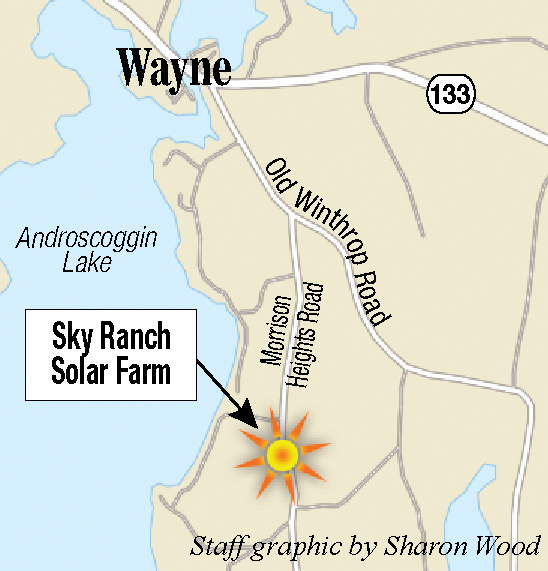

Like Holman’s airstrip, the solar farm is now known as “Sky Ranch.”

Besides being a tribute to her father, that name also hints at the reason Graef, who inherited the land but now lives in Portland, and eight other Central Maine Power customers collectively contributed $200,000 to have the photovoltaic panels installed.

Community solar farms, as such setups are known, are designed for those ratepayers who would like to get their electricity from the sun, but can’t install solar panels on their own home for whatever reason: Their rooftops aren’t large enough, they rent an apartment, trees block the sunlight.

Shade isn’t an issue at Sky Ranch, where on a recent weekday afternoon the rays were coming down unabated. They were striking the five south-facing units, getting converted to a direct electric current at inverters attached to each unit and flowing out onto transmission lines owned by Central Maine Power.

The farm’s total output is measured by a CMP meter at the entrance to the property.

The nine ratepayers who invested in the farm now see a credit on their power bill for the amount that’s generated. They pay fees to CMP for delivery and other services and leasing fees to Graef, who owns the land underneath the solar panels.

The design and construction of the array took about six months. It went online earlier this spring, becoming the fifth such array in Maine, according to engineer Hans Albee of ReVision Energy, the company that carried out the Sky Ranch project.

Albee said another five community solar farms are in the works for 2016, including one in South China.

Such farms do not account for a very large share of the state’s power mix.

And when it comes to size, they don’t compare to some of the larger solar arrays either built or planned around the state. The Wayne farm’s generating capacity, 49.6 kilowatts, is less than 5 percent of what Bowdoin College generates at its 1.2 megawatt array. Colby College is planning to build a 1.9 megawatt array, and a developer is moving forward with a 50-megawatt solar project in Sanford, which could be the state’s largest.

But the growth in smaller solar projects at the community, rooftop and municipal scales does hint at the rising demand for renewable energy sources around Maine and the shrinking costs of solar power equipment.

For Graef, the investment in solar energy now won’t pay off for at least a decade. That’s when her upfront costs will be completely offset by the credits she has earned on her power bills. Still, she takes heart that fewer fossil fuels will ultimately get burned to satisfy her energy needs.

“It would be nice to have savings, but that was not really the prime motivator for me,” she said. “I really feel very strongly that every single thing that we have here is from the sun ultimately. The sun is doing all this stuff, and we’re stupid not to exploit that. I was a science teacher. I consider myself an environmentalist. When I saw that they were looking for places to position these solar farms, I was very interested, and I thought it would be a good fit. You want to do things to help your society.”

Another bonus, Graef added, is that the solar array helps preserve the land and views at her childhood home. While gardens would have the same effect, it would be tough to convert the land there to fertile soil, she said.

Whether more Maine customers can get energy savings from solar is an open question.

The ability of solar power to meet Maine’s energy needs recently came under the microscope, when lawmakers approved a bill that aimed to add 196 megawatts of solar to the state’s power mix over the next four years, but were not able to override Gov. Paul LePage’s veto of the bill.

Although the bill was supported by a range of parties who don’t always see eye-to-eye — solar advocates, environmentalists, utility companies, the state’s public advocate — LePage argued it would favor one energy source over another and raise the state’s electricity costs.

The law would have changed how solar power is priced, and some supporters argued those changes would encourage larger scale solar projects that lower costs for all energy consumers.

Charles Eichacker — 621-5642

Twitter: @ceichacker

Send questions/comments to the editors.