Remote, rugged and heavily wooded, the terrain surrounding Maine’s portion of the Appalachian Trail likely contributed to hiker Geraldine Largay’s death in two ways.

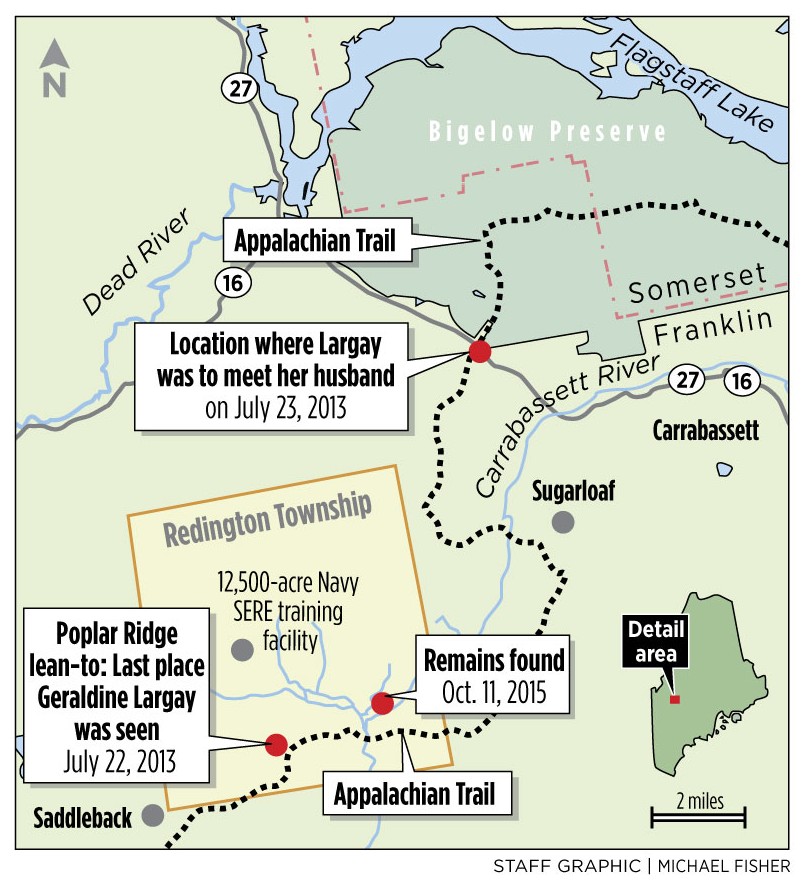

It probably was a factor when Largay, who reportedly had a poor sense of direction, became lost after stepping off a section of the trail in northern Franklin County for a bathroom break on July 22, 2013. Then it hampered searchers during a rescue effort that failed to find her, those familiar with the trail say.

She died after weeks in the wilderness, leaving behind a journal and a cellphone that provided some clues to her plight when her remains were found in October 2015. Entries from the journal and a transcript of text messages she tried to send from her cellphone were part of the 1,579-page case file released Wednesday by the Maine Warden Service.

The 66-year-old Largay was an experienced hiker from Brentwood, Tennessee, who planned to through-hike the trail. While questions remain about how she lost her way after leaving the trail for what was likely a relatively short distance, those familiar with the unforgiving nature of the swath of Maine land that the trail cuts through aren’t surprised.

“Maine has some of the most rugged terrain on the Appalachian Trail,” said Doug Dolan of the Maine Appalachian Trail Club, a group of volunteers who maintain portions of the trail. “When you get off the trail, there’s very dense vegetation. You can’t see more than 6 feet in front of you.”

CAMPFIRE COULD HAVE AIDED SEARCH

Dolan said the trail itself is 4 feet wide, well-maintained and well-marked, but the markings are designed for hikers who stay on the trail.

“If you get off the trail, it can be difficult to find your way back to civilization,” Dolan said. “You really have to pay attention.”

Dolan advises hikers who go off the trail to mark their path. That’s key, he said, both to help hikers find their way back, and to allow someone searching for them to see where they left the trail.

He said if Largay had built a campfire, the smoke would have helped wardens find her. Setting up a tent in a spot with the least amount of tree canopy also could have helped, because wardens search by air for signs of lost hikers.

“It’s really difficult for them to do the searches on foot, because of how dense” the woods are, Dolan said.

The warden service conducted an intense seven-day search immediately after Largay was reported missing by her husband, on July 24, 2013, and periodically searched for her over the next 26 months. Her husband, George Largay, was meeting her at designated checkpoints, and called authorities when she failed to show up at a checkpoint.

Geraldine Largay kept a journal that was made public Wednesday, indicating that she set up a tent in a heavily wooded area about 2 miles from the trail. She survived for at least 26 days before dying from a lack of food and water and from environmental exposure, the warden service said in its report on the search for Largay and the eventual recovery of her body. She was found in her sleeping bag inside a zipped tent.

She had tried to text her husband, but the texts did not go through because of poor cellphone service in northern Maine.

Largay was hiking alone – another risk factor – after a friend she was hiking with left the trail because of a family emergency. The friend, Janet Lee, also told the warden service that Largay didn’t know how to use a compass.

‘MAINE IS PROBABLY THE TOUGHEST’

Lee also told the warden service that Largay had a poor sense of direction, and would become easily flustered when she made a mistake. The report also said she was scared of the dark and of being alone.

She was also a slow hiker, giving herself the nickname “Inchworm.”

Hiking the Appalachian Trail has become more popular in recent years, spurred by publicity from best-selling books and a 2015 Robert Redford movie based on the book “A Walk in the Woods,” by Bill Bryson.

The number of people who have successfully completed the entire trail from Georgia to Maine has increased steadily, from 526 in 2007 to 928 in 2014, according to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, a national group that advocates for the trail.

“There’s a lot more people interested in doing the Appalachian Trail,” said Sandy Bell, co-owner of the North Woods Trading Post in Millinocket, which bills itself as “the last stop for gas, gear and supplies before Baxter State Park and Mount Katahdin.” Katahdin is the northern end of the 2,184-mile trail that begins on Springer Mountain in Georgia.

“There are people who are very well-equipped for the hike, and a whole group that’s not,” Bell said. “If they come in wearing flip-flops and say they’re going to hike the Appalachian Trail, we have a talk with them.”

Bell said the store sees a lot of people who are trying to hike the trail from north to south, but people who aren’t well-prepared often will give up, their enthusiasm dampened after the grueling ascent of Mount Katahdin and trying to hike through the rugged woods in northern Maine.

“Maine is probably the toughest part of the whole Appalachian Trail, and if you’re not prepared, that’s where problems set in,” Bell said.

MOST LOST HIKERS FOUND QUICKLY

An average of 28 Appalachian Trail hikers get lost in Maine each year, the warden service said. But they’re almost always quickly found: 95 percent of the time, searchers locate them in 12 hours, and 98 percent of lost hikers are found within 24 hours.

Bell said there are many books on how to prepare for the trail, including what gear to bring, how to use the U.S. Postal Service to re-supply, and other tips to complete the 2,184 miles of trail. Hiking the entire length can take five to six months.

Dolan said southern parts of the trail are wider, with less vegetation and many more people hiking, so getting lost is less likely. But most of the hikers who begin the trek have dropped out before reaching Maine.

About 2,500 people began an attempted through-hike at the trailhead in Springer Mountain in 2014, but only 653 accomplished the feat, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy said. Others complete the full trail by going north to south, or by completing it in sections.

Send questions/comments to the editors.