SKOWHEGAN — Claudia Viles was “sort of a free-range chicken” who was unsupervised as she stole about $100,000 a year from the Anson Town Office between 2009 and 2014, Assistant Attorney General Leanne Robbin told a jury in Somerset County Superior Court Monday morning.

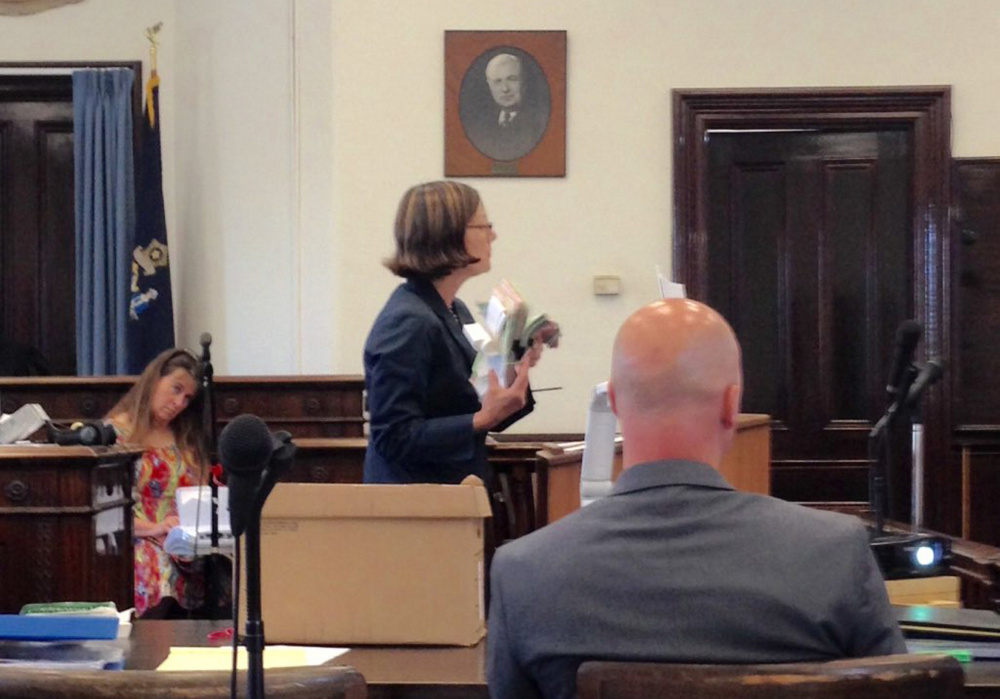

Viles, 66, the former Anson tax collector, is charged with 13 counts, including a Class B felony, for allegations she stole excise tax money collected by the town. Monday was the first day of Viles’ trial, which is predicted to last through most of the week.

Monday’s witnesses included a parade of current and former town employees and officials who testified that Viles had no oversight, no one kept track of the excise tax money she collected, she resisted learning to use a computer, attempts to make collections and deposits more efficient were ineffective, and once discrepencies were pointed out, related paperwork began to disappear from the Town Office.

Investigators for the state have not released an exact figure for how much they believe Viles stole, but Robbin told a jury of seven women and eight men that she took about $100,000 a year over six years.

Viles’ attorney, Walter McKee, said Monday in opening statements that anyone could have taken the money — including inmates from the Somerset County Jail, who helped move the town office in 2014 — but the investigation only focused on Viles.

Viles, who is free on bail, declined to comment outside of the court. She was the elected tax collector in Anson for 42 years before her resignation in September. About two dozen people attended the first day of the trial, including Viles’ husband, Glenn Viles, and son Dan. They also declined to comment.

The discovery that the town was missing money came with the implementation of a new computer system, Triss Smith, the former town administrative assistant, testified.

At the end of 2014, Smith ran a report on the computer system that the town had started using that September, indicating that the town had collected $354,355 in excise taxes for the year, but Viles had presented her with a number that was about $78,000 less, Smith testified.

“I didn’t know what to think or where to go from there,” said Smith, who said she reported the discrepancy to Arnold Luce, chairman of the selectmen, who organized a meeting with Richard Emerson of Purdy Powers & Co., who had conducted the town’s audits in the past.

At that meeting in February 2015, Viles told Luce and Emerson that she was responsible for the shortfall and would pay it back, Luce said.

“I don’t think she realized then how much we were talking about,” Luce testified. He said he later visited Viles at her home and said she was shaken up and told him there was “no way” that the town was missing about $78,000 in excise tax money for 2014.

Shortly after that, Viles was called into an executive session with the board of selectmen where they asked her if it was the first time a discrepancy had been noted and she said yes.

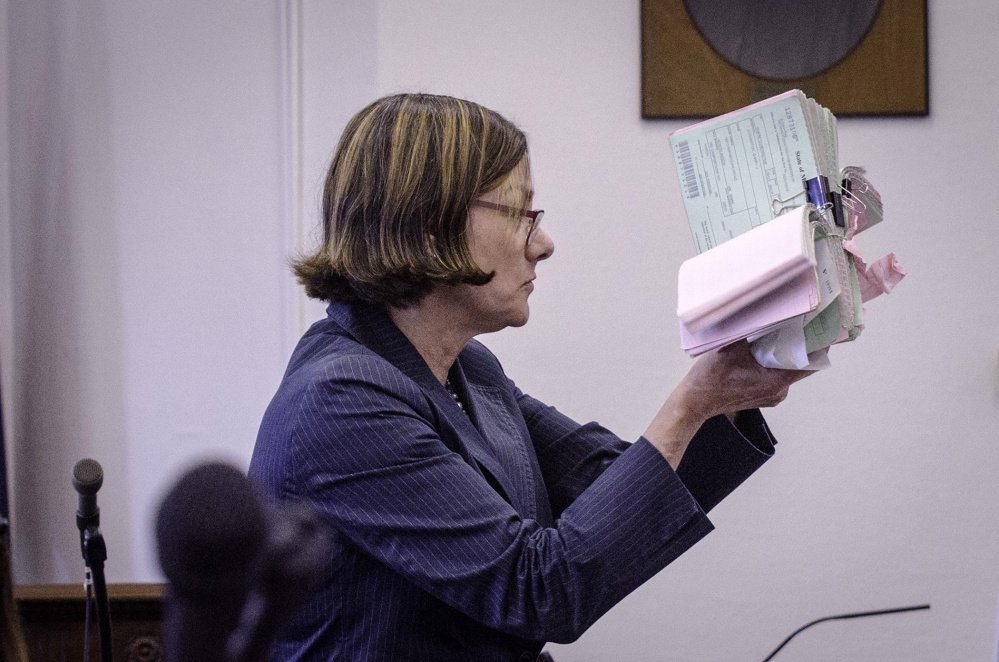

Around the same time, Smith noticed that the motor vehicle registration forms were missing and Viles said that she had taken them out of the office. The town produced a letter from its attorney asking Viles to return the files, and she “eventually did bring them back piecemeal,” Smith said.

To date the town is still missing copies of records for the first three months of 2013 and all of 2010, officials testified.

In April 2015, Maine State Police seized $58,500 in cash from a safe in Viles’ garage. McKee told the court Monday that the money belonged to Viles and that her bank statements do not show any record of money deposited other than what she was paid by the town.

About a month after the cash was seized from Viles’ home, Smith resigned from her job, saying that the atmosphere at the town office “was getting hard to be in.”

“I spent my last couple days recalculating motor vehicle excise tax receipts,” she testified.

WHERE’S THE MONEY?

McKee said investigators didn’t look deep enough. “We all jump to conclusions because we think we know how things go, and that’s exactly what the state did here,” McKee said in opening statements. “Early on they looked at the money that was missing, then looked at the person who collected it and decided that she must be the person who stole it.”

He also questioned where the missing money is. “Is the missing money in her accounts? No, it isn’t,” McKee said.

“You don’t see Claudia driving an Escalade or taking off on vacations to Hawaii. You see her depositing her own checks, and the state still has not found that $450,000.”

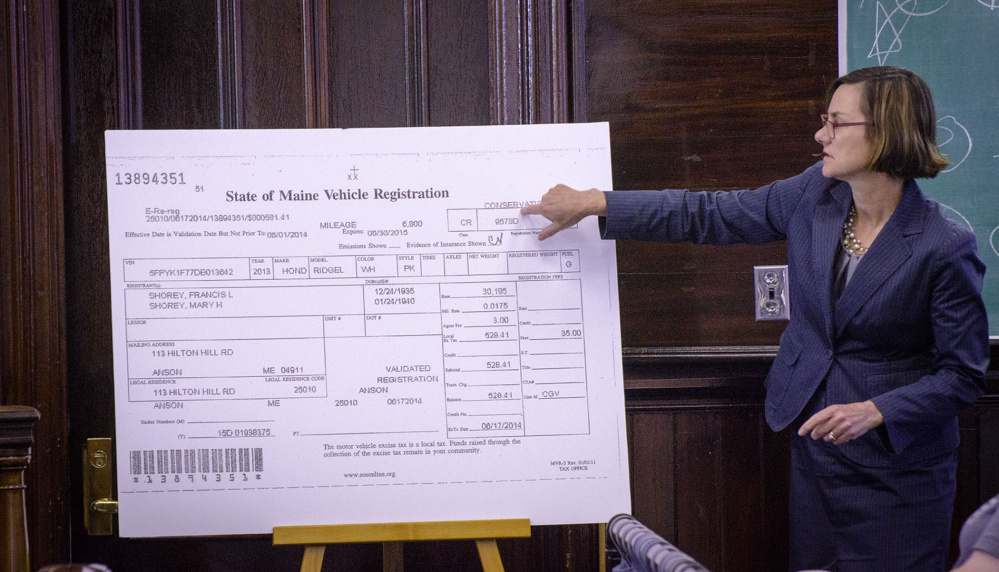

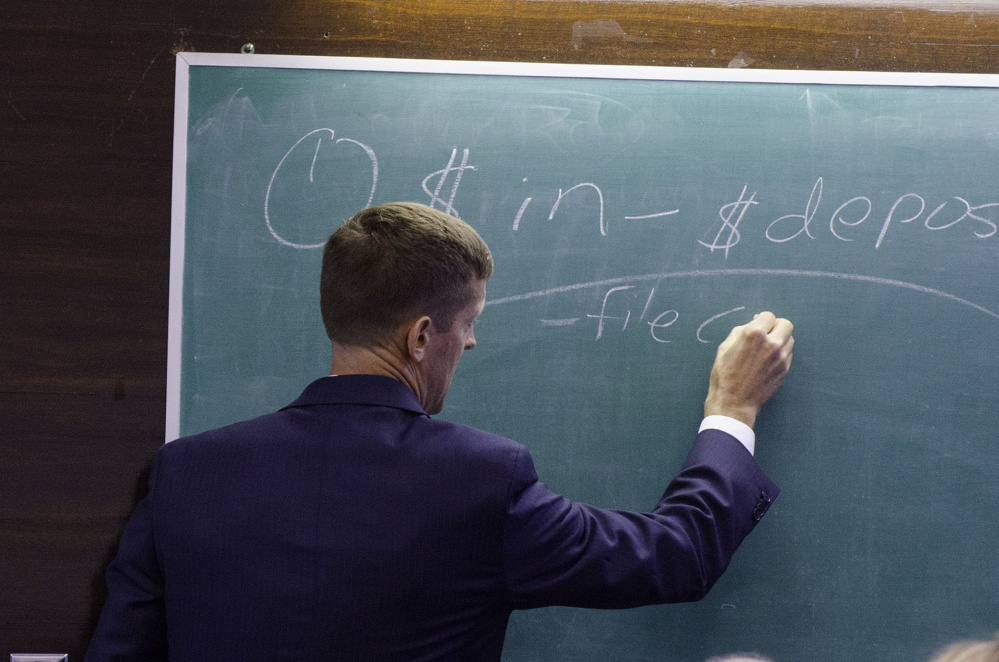

Robbin, in her opening statement, pointed to several bookkeeping discrepancies made by Viles that she said were unexplainable, mainly that the amount of excise tax taken in was not properly recorded on treasurer’s receipts and bank deposit slips, which Viles was almost solely responsible for filling out while she worked as tax collector. The motor vehicle registration forms that Viles filled out as she collected money from residents were never checked by anyone to determine if the amount of money collected matched what was deposited, Robbin said.

When the town’s auditing firm, Purdy Powers & Co., conducted annual audits, they checked the treasurer’s receipts to make sure they matched the deposits and the total of Viles’ calculator tapes.

“But no one ever asked Claudia Viles to turn over all the excise tax forms, and no one ever added up the tax on each one to figure out whether the number she gave was the right number,” Robbin said. “If they had done that, they would have discovered that Claudia Viles had skimmed the cash from the excise tax before she filled out the treasurer’s receipt and handed money over to the treasurer.”

Several witnesses Monday testified that there was no oversight over Viles’ position, and no system of checks and balances when it came to excise payments — local taxes on motor vehicle registrations and other property — and deposits.

Smith and Robert Worthley, who was administrative assistant from 1998 to 2014, both testified Monday that they signed off on the treasurer’s receipts without ever checking the motor vehicle registration forms to see how much money was actually collected.

Both said they had no supervisory capacity over Viles, and that they did not know what she did with the money she collected.

Worthley said that when he started in 1998, Viles worked out of her husband’s construction garage in Anson. She conducted business as the tax collector there for about two or three years before she moved into the Town Office.

“I’m not sure what her motivation was (for moving),” Worthley said. “I encouraged it because I thought it would be a better way to serve the community, but I had no supervisory capacity over her.”

Worthley testified he had several conversations a year with Viles about the need to deposit money into the town’s accounts in a timely manner, and each time she would say she was working on it. An affidavit filed as part of the investigation said that Viles made deposits quarterly.

Worthley said residents complained that their checks were not being cashed, and as a result the town adopted a financial procedures policy stating that daily deposits of town money were preferred.

“It worked for a little while, but then she started to slip back,” he said. “Very seldom were there daily deposits.”

Worthley said he did not know where Viles kept the money she was collecting, though he presumed it was in a file cabinet in her office. He often saw her carrying two large bags of paperwork to and from the building each day.

“It turns out there was a fair amount of town money being transported back and forth in those bags,” he said.

Several women whom Viles hired to help her at different times of the year also testified that they did not know what Viles did with the money that was collected and said that she would always pay them in cash for their work.

Both Amanda Morrill, of Embden, and Katharine Leeman, of Anson, said that they were hired by Viles to check weekly motor vehicle reports prepared by Viles, but those reports only included information on the number of registrations processed and money that was due the state, not excise tax figures.

“I thought the reports must have included excise tax figures, but now that I’m looking at them I see they don’t,” Leeman said when presented with one of the reports by Robbin.

Town officials also testified that every year she would put a bid in for her position at the town meeting and voters would approve to pay her a percentage of the excise and property taxes collected, as well as agent fees — a fee of a few dollars that is charged with each vehicle registration. The town would cut her a check based on requests she submitted to the board of selectmen and she would collect and retain agent fees herself.

NO SECURITY

McKee said a lack of proper security measures at the Anson town office, including no surveillance, also raised questions. A copy of the key to Viles’ office hung on the wall of the Town Office for anyone who walked in to the office to see and potentially use. “The money taken in was left virtually unattended,” he said.

When the new Town Office opened in 2014 and the records and belongings were moved, the town used inmates from the Somerset County Jail who were part of a work release program.

McKee asked several former and current town officials Monday whether it was possible that inmates had handled town records or money, but the officials gave no indication they suspected any of the inmates of wrongdoing.

Luce, selectmen chairman, said he didn’t remember participating in the program, and Worthley said that shortly after the move, the town changed the keys to the office.

Only Carol Ryan, a former town clerk and secretary, testified she saw something strange around the time of the move — an extra key to Viles’ file cabinet, where she was believed to have kept money and which also contained town records was lost around the time of the move. What happened to it “was a mystery for a while,” Ryan said. The key reappeared in her own desk a few months later, Ryan said.

Town officials did not go into Viles’ office or the file cabinet unless it was during business hours and she was there, though one exception was former selectman Phil Turner, who would often visit with Viles at her office “a lot more than the other selectmen,” Ryan said.

Around the time of the move to the new Town Office, Worthley retired and the town hired Triss Smith, a former Madison tax collector and finance officer as his replacement.

It was then that Viles’ “way of doing business and her opportunity to steal came to a screeching halt,” Robbin said.

Smith introduced a new software program that mandated daily cash deposits.

Before that, Worthley testified, the town had been encouraging Viles to computerize her job, but she resisted saying she wasn’t good with computers. When Worthley started in 1998, Viles was using a manual typewriter to complete motor vehicle registrations and it was several years — he estimated around 2012 — before she began using a computer to fill out the forms.

Luce testified, “Over time different aspects of her job became computerized, but it wasn’t until 2014 that the final components of her job were done on the computer.”

Rachel Ohm — 612-2368

Twitter: @rachel_ohm

Send questions/comments to the editors.