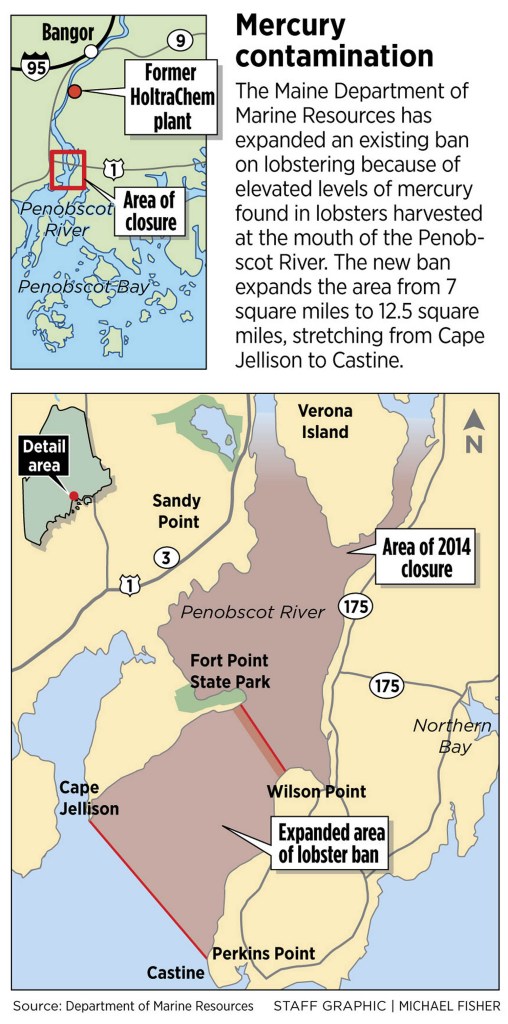

Maine has expanded its ban on lobstering and crabbing in a small section of Penobscot Bay after finding elevated mercury levels in lobsters tested south of the existing no-fishing zone.

The Maine Department of Marine Resources had declared seven square miles of the Penobscot River estuary off limits to lobstermen and crabbers in 2014 after a federal court-ordered study detected elevated mercury levels in lobsters found as far south as Fort Point on the west bank and Wilson Point on the east bank. On Tuesday, based on the results of state-funded tests done after the initial closure, the department announced it would add 5.5 square miles to the no-fishing zone, extending it south to Squaw Point on Cape Jellison and Perkins Point in Castine.

The average amount of mercury found in the tails of legal size lobsters harvested off Cape Jellison in testing done in 2014 was about 292.7 nanograms per gram of tissue, according to state findings. That exceeds the 200-nanogram threshold recommended by the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention – the Department of Marine Resources uses that level to decide if an area is unsafe to fish – but is lower than the 350 nanograms of mercury per gram of tissue found in canned white tuna, officials said.

“We are adding this very small, targeted area to the closure so consumers can continue to be confident in the exceptional quality of Maine lobster,” said Marine Resources Commissioner Patrick Keliher.

INDUSTRY PROTECTIVE OF BRAND

Nearly all fish and shellfish contain traces of mercury, but some fish and shellfish contain higher levels of the heavy metal, which may harm the developing nervous system in unborn babies and young children. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration says pregnant women, nursing mothers and young children should not eat fish that contain high levels of mercury, like swordfish, and should eat less than 12 ounces, or about two average meals a week, of fish that is lower in mercury, like shrimp, canned light tuna or salmon.

The state doesn’t know how many pounds of lobster are usually harvested from the 5.5 square miles in a typical year, or how many of the state’s lobstermen fish that bottom, Department of Marine Resources spokesman Jeff Nichols said. Lobstering licenses are issued by zone, and lobstermen can fish anywhere within that zone, although in practice a lobsterman usually drops traps in the same spots each year. Lobstermen also can sell their catch at any port they want, which makes tracking the fishermen most impacted by the expanded no-fishing zone difficult.

The Department of Marine Resources estimated 270 licensed commercial and recreational harvesters worked in the area closed to fishing in 2014.

Maine’s 3,500-mile coastline is divided into seven lobster management zones. The 12.5-square-mile area at the mouth of the Penobscot River now closed to lobstering is a tiny part of Zone D, which stretches from New Harbor to Belfast. In 2015, the 1,100 or so lobstermen who fished Zone D landed 24.4 million pounds of lobster valued at $101.9 million, which made it the second busiest and third-highest grossing zone in the state, according to state data. The overall landed value of Maine’s lobster fishery topped $495 million in 2015.

Lobstermen never want to see an area closed, but they have supported the Penobscot River ban because they want to protect the long-term reputation of the product, said Patrice McCarron, president of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association. She said the impact of the 2014 closure has been limited because it is an area where a handful of local commercial lobstermen would only fish for a four- to six-week period during late summer. She hasn’t had a chance to talk to any of the locals about the expanded closure, but she expected the impact of the additional measures to be similarly limited.

“We are just relieved the state is doing all it can to protect the brand,” McCarron said. “We depend on that brand. People need to know that Maine lobster is exceptionally safe. Harvesters understand that better than anybody.”

NEW SAMPLING LED TO WIDER BAN

The mercury contamination in the Penobscot River was revealed in a court-ordered study conducted as part of a 17-year-old federal lawsuit filed against the owner of the former HoltraChem chemical plant in Orrington. The judge ordered Mallinckrodt US LLC last fall to pay to develop a mercury cleanup plan for the Penobscot River. The remediation costs have been pegged at about $130 million, which would make it one of the largest and costliest environmental cleanup projects in Maine history.

Mallinckrodt, a St. Louis-based company, owned and operated the factory from 1967 to 1982. Unbeknownst to state officials, the factory discharged mercury directly into the river at a rate of 1.5 to 2.5 pounds per day during its early ownership. Discharge levels declined after 1970, but some discharges of the toxic heavy metal continued through 1982, according to court documents. A later operator, HoltraChem Manufacturing Co., shuttered the plant in 2000 and declared bankruptcy, but Mallinckrodt was deemed responsible for the cleanup as the sole remaining former owner still in business.

The closure announced Tuesday is based on state evaluation of testing it hired a contractor to do in 2014 after it had closed the first area, Nichols said. The state wanted to confirm the findings in that court-ordered study, and make sure the southern border of the closure zone covered all waters where lobsters with elevated mercury levels could be found, especially given that lobsters migrate, he said.

The state-funded sampling found elevated levels in some areas south of the 2014 closure line that had tested below the 200-nanogram threshold in the court-ordered Penobscot River Mercury Study. State scientists believe that is due to a difference in sampling methodologies. The court-ordered study tested for mercury at one time of the year, while the state-funded sampling tested at different times of the year, which enabled it to detect the seasonal fluctuations in mercury levels that put areas south of the 2014 closure line over the 200-nanogram limit.

Send questions/comments to the editors.