W

hen Horace Beals took granite from Rockland to other parts of Maine, he’d often hear stories about the curative waters of the Kennebec River. So when he tired of the quarry business, he decided to buy acreage near the river with the hopes of building a Saratoga Springs-like resort.

Beals traveled the world to find wallpaper and tapestry and other luxury items for a 150-unit hotel under construction on the property, which he called Togus Springs. The name Togus comes from the Native American name “Worromongtogus,” which means mineral water. He had everything ready, except there was no road to get to the property, so Beals sunk a lot of money into the project. In 1859, however, there weren’t a lot of people traveling to Maine hoping to find curative water, so the opening of the Togus Springs hotel was underwhelming, according to Maine State Archivist David Cheever.

But from the failure of the resort emerged a new life for the Togus property as a first-of-its-kind veterans’ care facility. A review of historical records and newspaper articles at the time and interviews with experts illustrate the sweeping impact Togus has had on veterans’ services over the last century-and-a-half, paving the way for a national model of residential care that forever changed the way U.S. veterans were treated after returning from combat. Those changes occurred even as Togus suffered setbacks of burned-down buildings, deaths on campus and tension over alcohol prohibition, while the property transformed from a planned recreational resort into a groundbreaking federal veterans’ care campus.

“Its existence ushered in a new level of veterans’ benefits,” said Darlene Richardson, a historian with the Veterans Health Administration in Washington, D.C. “Never before had any major country provided medical care and housing for soldiers, sailors and marines who served as temporary volunteer soldiers.”

The story of the Togus transformation started with the failed Togus Springs hotel opening. Beals died unexpectedly a short time later, and his family took over the property. They had no idea what to do with it, so the property sat unused.

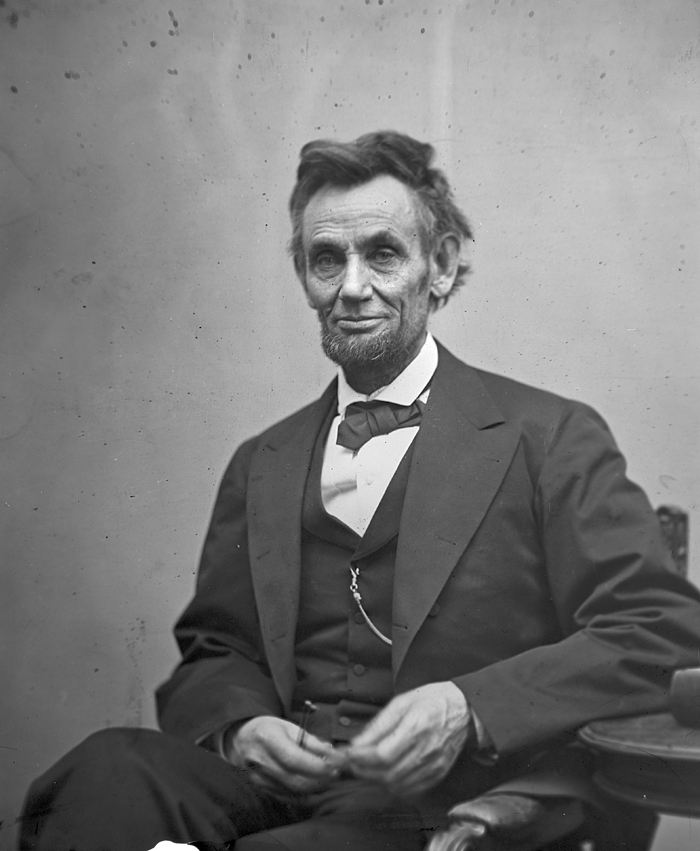

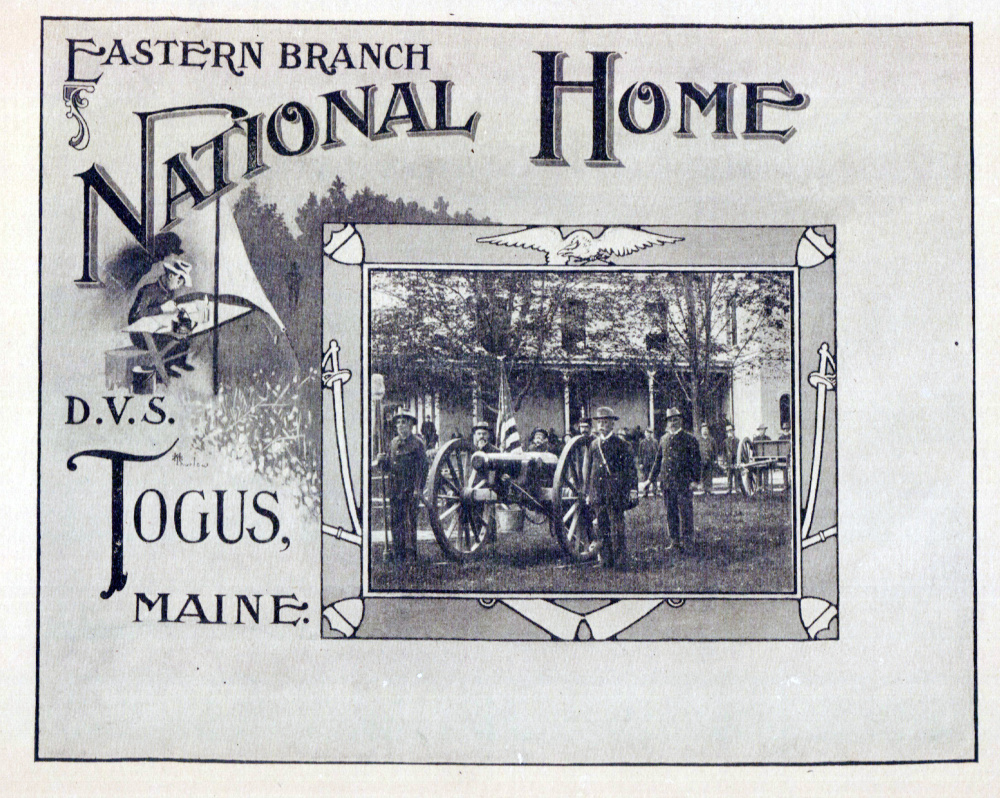

By signing his last piece of legislation before being assassinated in 1865, President Abraham Lincoln set up a network of homes for injured and disabled veterans to provide care for all the soldiers returning home after the Civil War. The network would be known as the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. The Togus property would be the Eastern Branch.

Maine’s congressional delegation 150 years ago identified the Togus property as being immediately ready because of the property’s hotel, so it was the “first one out of the starting block,” Cheever said.

Cheever said Union veterans started coming to Togus with the arrival of the first soldier, James P. Nickerson, of Company A, 19th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, in late 1866. An article in the Kennebec Journal from that year said the site was “comparatively new and eminently adapted to the use of the asylum.”

Before the Civil War, Richardson said, the National Asylum and the U.S. Soldiers Home offered hospitals and housing reserved exclusively for men who had served more than 20 years in the military.

When Togus opened, there were no models to use for reference, so the U.S. system of federal veterans’ homes and hospitals was built from the ground up, using Florence Nightingale’s environmental principles for good health.

“Worthy components and bits from the military and private sectors were added, and the system evolved as medical science evolved,” Richardson said. “From that first National Home in Maine grew the great federal system of veterans’ hospitals that we know today.”

EARLY LIFE AT TOGUS

Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, considered by Togus historian Donald Beattie to be the “father of Togus,” served as the president of the National Home’s Board of Managers for about 15 years. Despite the reputation he earned as a firm yet subtle leader during his occupation of New Orleans and other incidents throughout the Civil War, Richardson said Butler was “greatly committed to taking care of disabled soldiers after the war.”

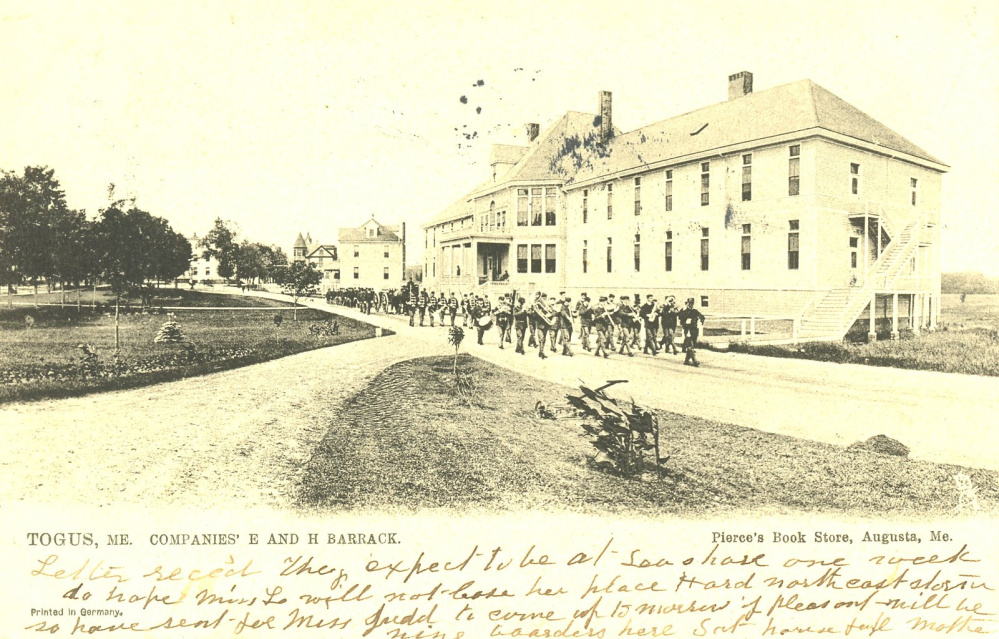

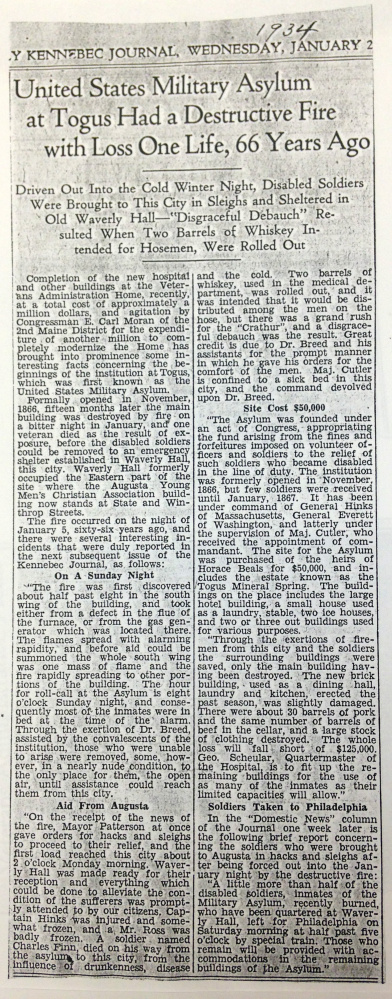

The asylum, as it was called then, opened in 1866. Veterans, who were known then as inmates, were treated in the former Togus Springs Hotel building until it burned to the ground in a fire in 1870.

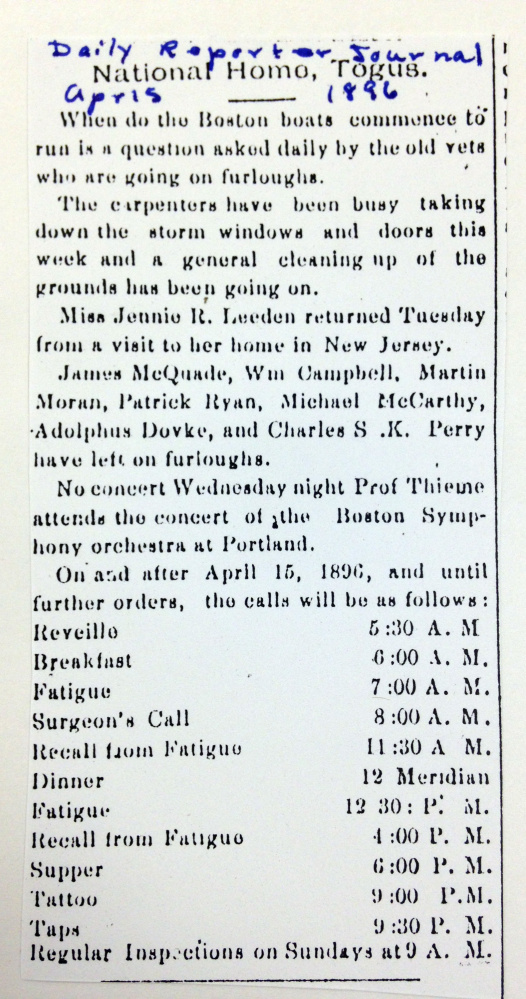

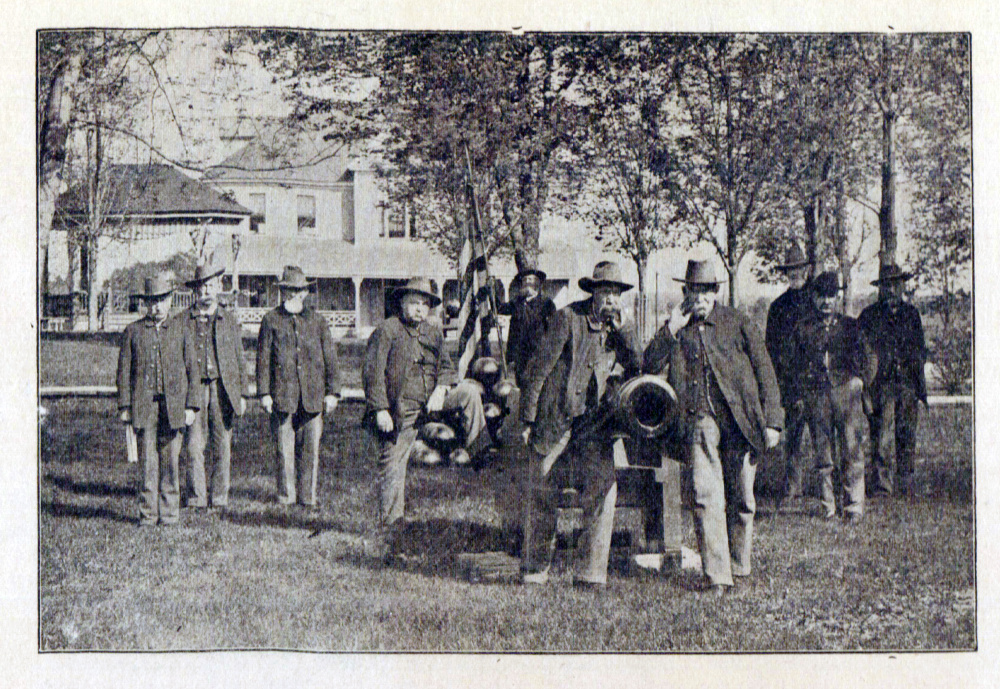

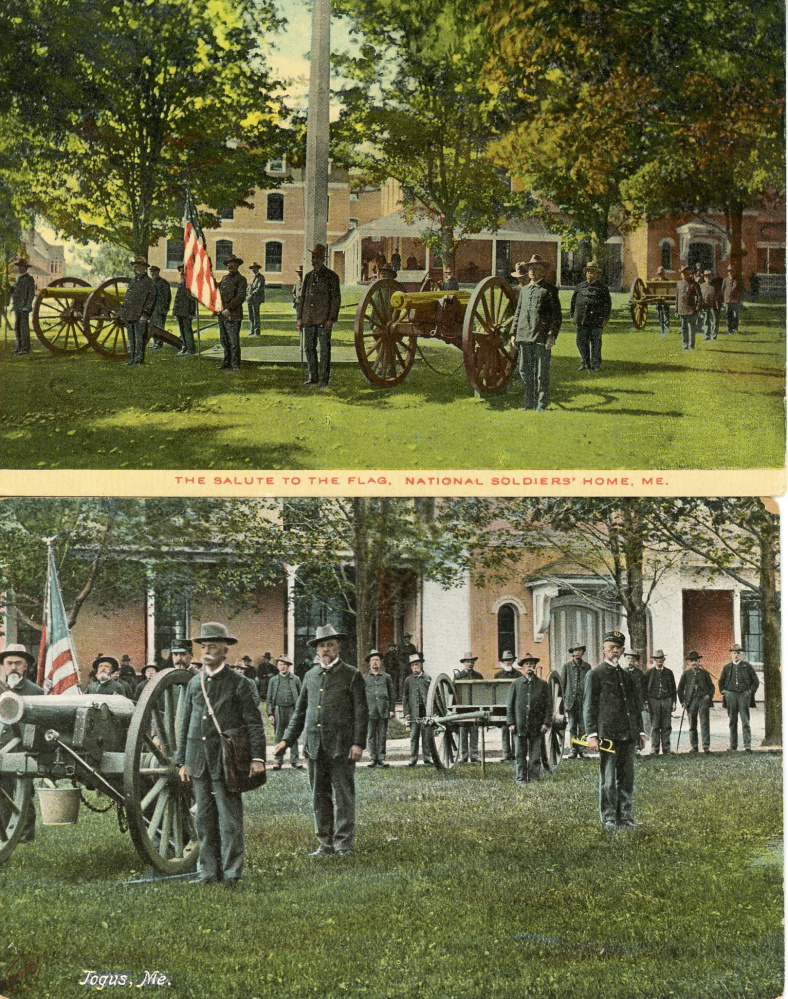

Early on, life on campus was similar to when the veterans were active members of the military — they were issued surplus uniforms, the nomenclature used was military-like — and bugles were heard throughout the day.

Veterans occupied their time in many ways, including working in the boot and shoe factory as part of a tradesman program. Within the first several months of the factory’s opening, veterans had made nearly 15,000 shoes; and by the end of the 1870s, veterans were making about 30,000 pairs per year.

An official policy in Togus’ early years stated inmates were required to work. Other jobs included that of a chief cook, which paid $20 a month; a police sergeant, which paid $15 a month; and a hospital barber, which paid $10 a month.

Veterans on campus had a variety of ways to keep entertained while they weren’t receiving care. An amusement hall was built and included a 500-seat auditorium and a small gallery. There was bowling, billiards and dominoes; and even though gambling was officially was prohibited there was also a small track for trotters.

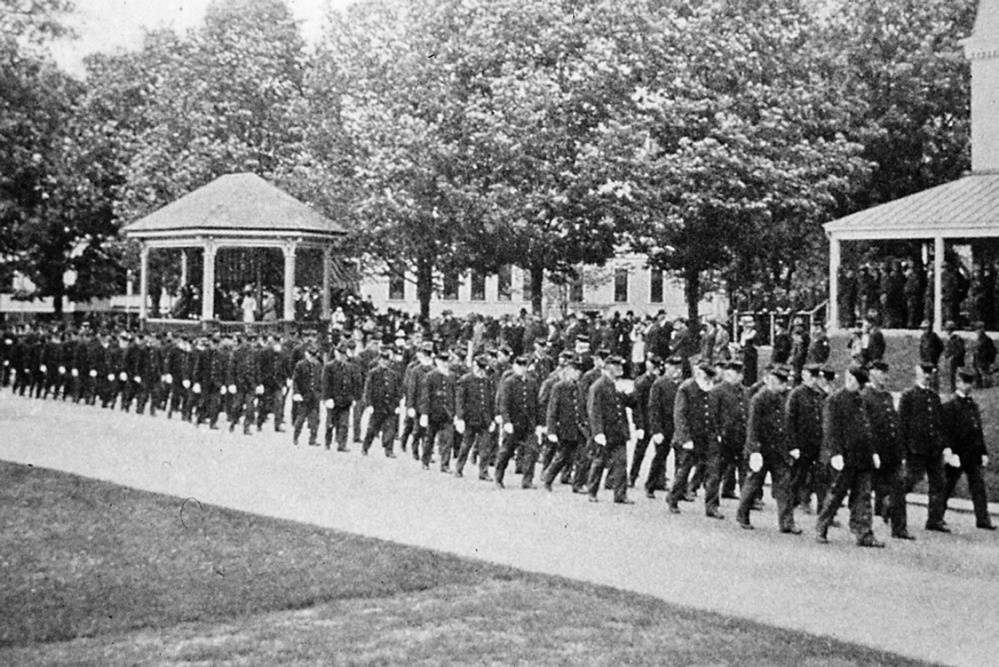

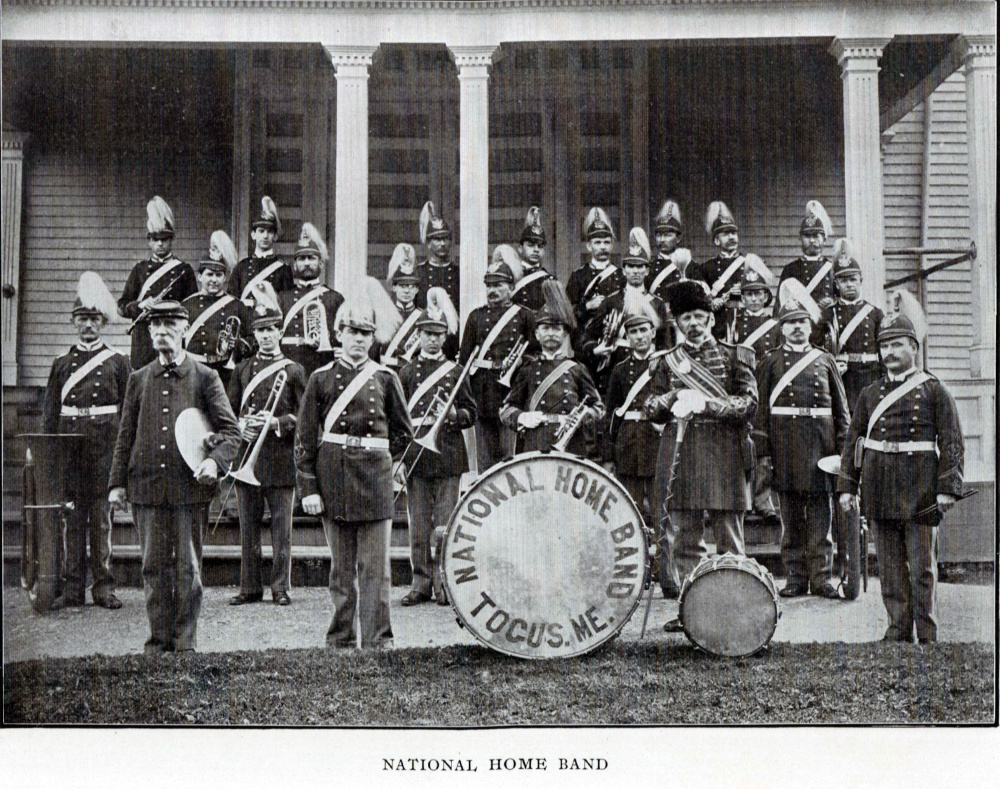

Lectures were given throughout the week on current events and topics of interest, including the Battle of Gettysburg and other Civil War battles. The National Asylum Band performed concerts regularly, opera productions also were held, and holiday parties were the norm.

The benefits provided to veterans, aside from regular health care, included discounted train and steamboat transportation throughout the U.S. and Canada.

The campus’ vast open space included a large farm with a large quantity of livestock. Veterans cared for horses and held other jobs throughout the farm.

Although Togus opened during a time of alcohol prohibition in Maine, bootlegging and drinking were tolerated unless flagrant offenses made action by those in charge absolutely necessary. Because of the relaxed atmosphere, rum sellers had an easy time peddling their concoctions. Soldiers sometimes were given whiskey to ease their pain, but other alcohol was officially prohibited.

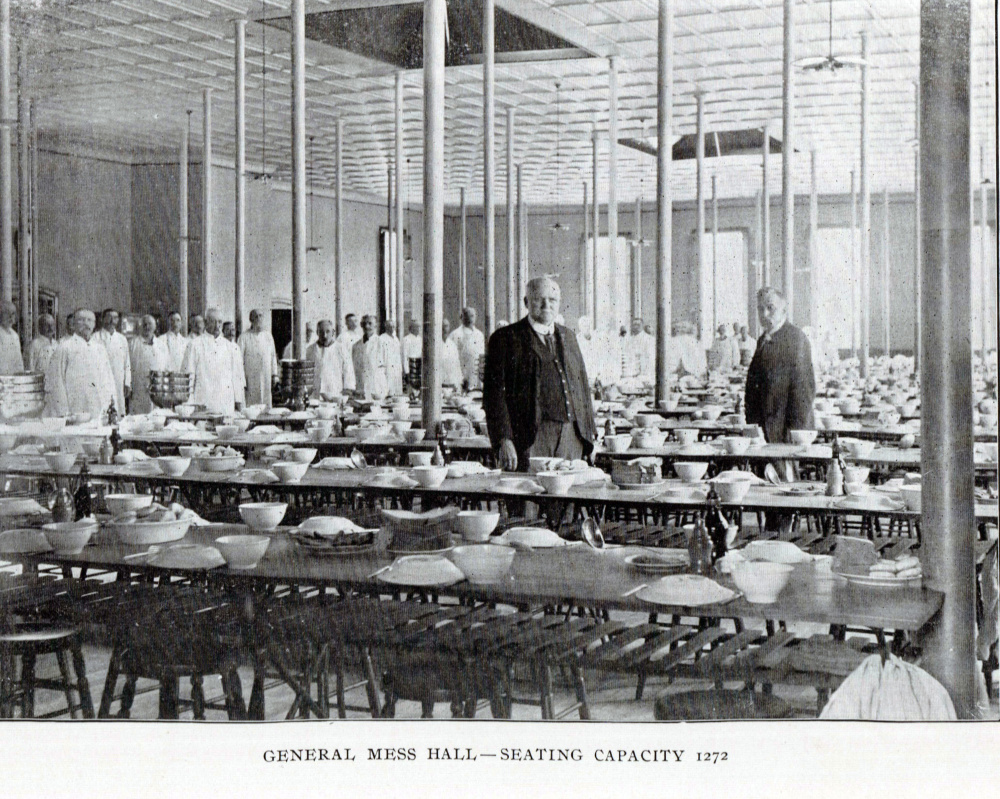

By 1880, Togus housed more than 3,000 veterans in the hospital and in private quarters. Early in that decade, a congressional oversight committee studied Togus and gave it a favorable report. A story from the Kennebec Journal shortly after the congressional visit said committee members listened to complaints from veterans and noted that all complaints were from the previous administration.

“The committee expressed themselves as much pleased with the appearance of the men, the cleanliness and neatness of their appeal being especially noticeable,” the article said.

But it wasn’t all good on the veterans campus.

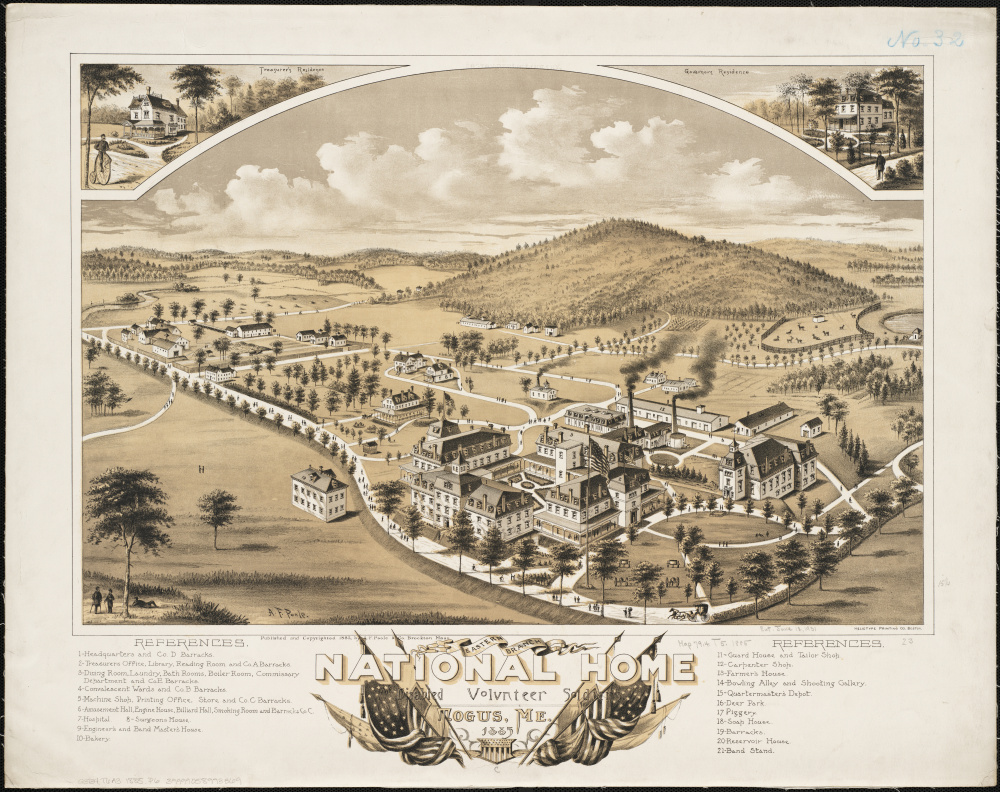

‘MINIATURE CITY’

Drunkenness was the chief source of disorder in Togus’ early years.

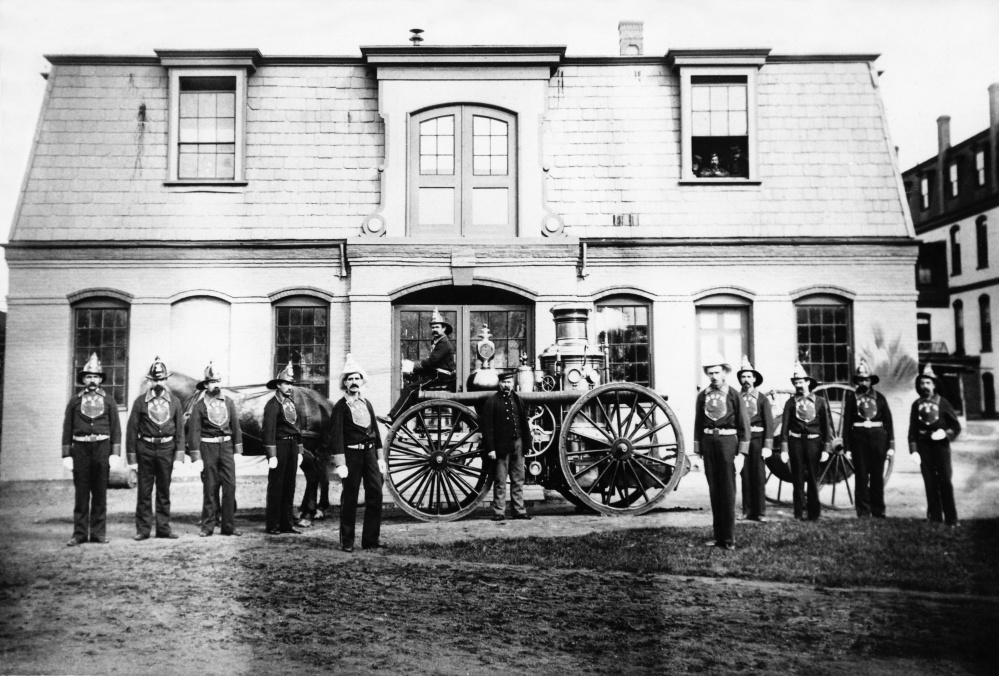

In 1867, James West was the first person to die at Togus after being punched during an altercation at a drinking hall early one morning, Richardson said. And Kennebec County Sheriff’s Deputy Thomas Malloy was killed in the line of duty in 1884 while attempting to enforce liquor laws. He was searching the carriage of a suspected alcohol dealer when a struggle ensued and Malloy was shot and killed.

The Narrow Gauge Railway and trolley service that was completed in 1890 brought people from all over to Togus, not just to visit disabled family members, but also to listen to concerts, tour the grounds and check out animals on the campus’s zoo.

In an article in the Lewiston Sun Journal Magazine, editor and writer L.C. Bateman, during a visit to Togus in 1905, called the facility a “miniature city” where “few or none but worn out veterans of the Civil War reside” and “make up a community that is as unique as any that can be found in all New England.”

The community continued to change and evolve throughout the early 20th century. As Civil War veterans got older, they’d often sit with younger veterans and share war stories for hours upon hours; these stories would get passed through generations.

Togus was becoming a full-fledged community with its own administration, its own night life, its own social structure and its own entertainment. Cheever said Togus worked with the nearby communities of Augusta and Chelsea, especially in terms of offering mutual aid in responding to fires.

At the same time, Togus also was losing its place among outsiders as an excursion opportunity.

The beer hall was closed permanently in 1907, the zoo was sold in 1923, and the Togus Brass Band folded, so the campus wasn’t seen as a spot for visitors as it had been in previous decades. But Togus would see a big change in the coming years.

NEW VETERANS NEEDS

In October 1930, the Veterans Administration was established by President Herbert Hoover and Togus officially became known as the Eastern Branch of the National Home, Veterans Administration. Along with the establishment of the VA, Togus underwent other changes throughout the next several decades.

Soundproofing in the mental health unit was a big advancement at Togus during the 1930s, and it kept patients from hearing others in the ward during what the Kennebec Journal articles described as “violent mental defects.”

After the end of World War II, Togus began its biggest shift to providing full-service care because of all the returning veterans who needed medical care.

Beattie, the Togus historian, said there was an accelerated emphasis on psychiatric care and a greater emphasis on reducing the number of patients living at the facility.

Patient care was supplemented by entertainment, athletics, the library, the campus canteen and chaplain services. Veterans continued to receive more than just acute medical treatment.

Those receiving treatment continued to have opportunities to keep themselves busy on campus. By midcentury, Togus was hosting Harry Houdini in the opera house while also fielding its own baseball team, which played an exhibition game against the Boston Red Sox in the late 1940s in front of 10,000 people at the Togus baseball field.

Patient care after World War II included supplementary care such as educational, physical, occupational, corrective and manual arts therapy. Around that time, Togus began hosting an annual sportsmen’s show featuring displays of fishing gear, boats and motors and other outdoor equipment as another way for veterans to add to their daily patient care.

A Kennebec Journal article from 1947 reported that nearly one-third — or about 31,000 — of Maine’s approximately 95,000 World War II veterans received medical attention and treatment at Togus.

PHILOSOPHY OF CARE

When the campus celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1966, Togus had 514 acres, 70 buildings, 7 miles of road, two cemeteries, two ponds, a dam and 2 miles of sidewalk.

“A large parade in sweltering heat” marked the centennial and included a replica Narrow Gauge Railroad, the Kennebec Journal reported at the time.

A number of important medical advancements were made as the facility entered the late 1960s. Notable achievements in patient care included mental health and suicide prevention; treatment of diabetes and cancer, including prostate cancer; pain management; and treatment for alcohol addiction.

The facility conducted a large portion of medical, surgical and therapeutic research, Beattie said, between the years after World War II and the 1980s, and it was one of the leading centers in the investigation of Legionnaire’s disease in the 1970s.

Post-traumatic stress disorder became a larger concern among staff members and veterans during the latter part of the 20th century. Togus opened its first unit dedicated to treating PTSD in 1986 and a formalized counseling program for PTSD began that same year.

It was during the 1980s that Togus started to think about Maine veterans who live outside major cities and towns such as Portland, Augusta, Waterville and Bangor. The first of Togus’ Community Based Outpatient Clinics, or CBOCs, opened in Caribou in 1987. And with technological advances that continue today, Togus and the VA continue to bring health care to veterans in rural areas.

The Togus campus in 1973. The main hospital building, Building 200, is at top right. The baseball field at top left was torn down for parking lots.

The 1980s also saw the implementation of a satellite television system, giving patients access to a wide range of television programs. Togus Child Care Inc. opened during the 1980s, and veterans had access to a large library containing tens of thousands of volumes.

As the century came to a close and Togus started treating veterans from the Middle East conflicts, it began to emphasize primary, specialty and preventive care in an outpatient setting. A new women’s clinic opened in 1998, offering female veterans privacy and a children’s play area; and a newer clinic was dedicated in 2014.

Now Togus has 10 outpatient clinics serving the more than 100,000 veterans across Maine, and its current director, Ryan Lilly, has laid out plans to continue to expand the campus to provide even more care for more veterans over the next decade.

“Togus was the pre-eminent veterans’ hospital and it has stayed as a primary-care, critical-care and residential-care option for veterans going back 150 years,” Cheever said. “As the wars have changed and the wounded have come in with different maladies and injuries and illnesses, Togus has stayed with the times.”

Cheever said as long as there are conflicts and as long as the U.S. maintains a commitment to care for the veterans of Maine, there will still be a Togus 150 years from now.

“There’s too much invested in the infrastructure and the facility and the whole philosophy of care,” he said. “You can’t walk away from that.”

Jason Pafundi — 621-5663

Twitter: @jasonpafundiKJ

Send questions/comments to the editors.