Michael Sholz’s house sits atop a hill overlooking hundreds of acres of field and forest with painting-esque views on a recent sun-filled day in Albion, golden grains shimmering below a crisp blue sky.

Sholz’s friend Henry Perkins, a farmer, grows grains in the fields and grazes Angus beef cows.

Everything in the 245 acres that is cropland will stay cropland forever, and everything that is forestland will stay forestland.

“Anyone who arrives in the driveway looks at this and says, ‘Wow, what a beautiful place,'” Sholz said while looking out on his property, which is called the Albion Bread Farm.

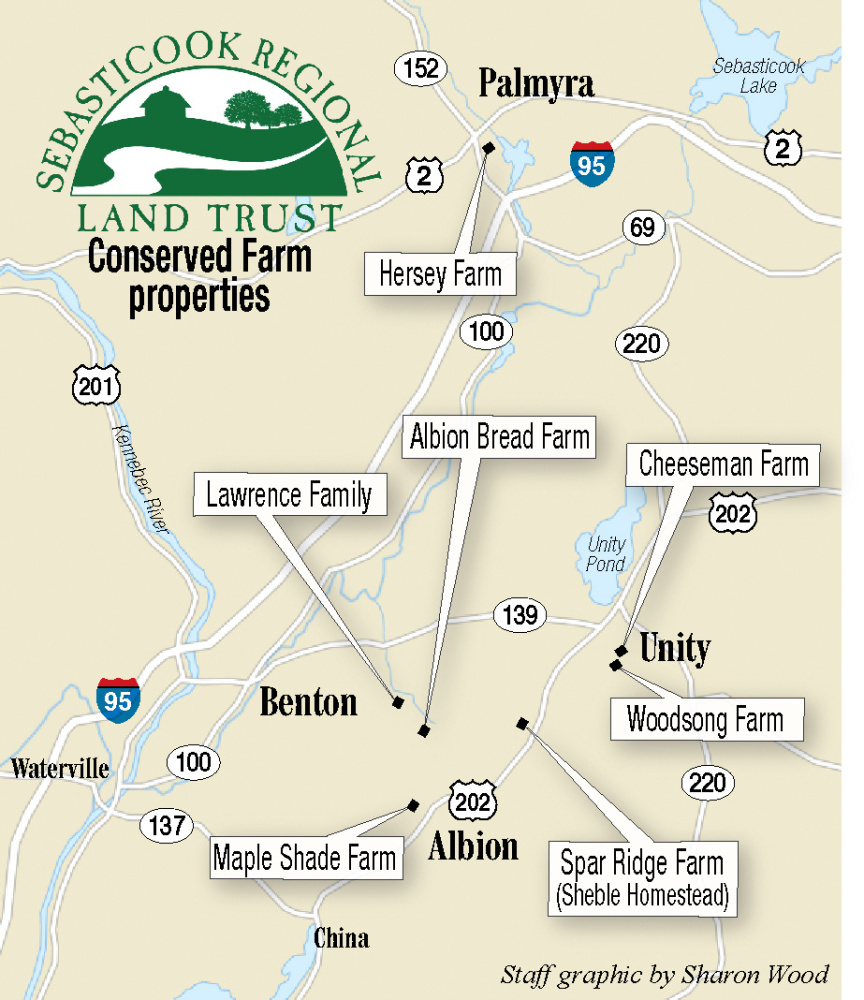

That’s the reason why Sholz chose to conserve the land with the Sebasticook Regional Land Trust in 2010, which works to conserve and restore land and waters within the Sebasticook River Watershed area. The land trust works with landowners who volunteer to conserve their land, so far conserving 1,800 acres that are owned privately and another 2,200 acres of “community lands” owned by the land trust itself. So far it’s placed seven pieces of farmland under easements.

Supporters of these conservation easements say they’re necessary to prevent developers from stealing Maine’s farmland away, while the state says too many farms could hurt the economics of the industry.

The number of farms in Maine is trending stable in recent years — hovering over 8,100, according to 2012 U.S. Census of Agriculture data, which is up by 1,000 farms since 2002 — even as the pace has slowed over the last 30 years of agricultural land being converted to developed land. A recent report by the Maine Forest Products Council estimated there are 17.6 million acres of land forested in the state, which is 89 percent of total land.

Mandating that land be farmed under an easement comes at a price: Maine farm wages have been stable over the last decade, but costs continue to increase. And while an easement has provided many landowners with the peace of mind that their land will always be protected from becoming another housing development, cul-de-sac or strip mall, the arrangement also can leave some in a tough position when they want to sell.

Just ask Annie Sheble, who bought land to create Spar Ridge Farm in Unity in 2004. By 2006, the land was conserved with an easement, though now she regrets agreeing to restrictions that came along with that deal.

Sheble said she became familiar with the Sebasticook Regional Land Trust and its mission after moving to Unity and decided to conserve her property to keep it intact. The owner of a large number of acres in the area was “clearly subdividing” his property, of which Sheble bought 45 acres.

Originally, in the 1930s, the land had been used as a bean farm. It wasn’t broken up until the 1980s, when someone bought it and started to rebuild the old farmhouse on the property. The land already has been divided into five parcels, Sheble said.

Most of Sheble’s acreage is woodland, which she wanted to conserve. She first went to Maine Farmland Trust, which wasn’t able to secure grants for the property, and then the Sebasticook land trust.

About a quarter-acre is used for gardening and growing fruit trees, 5 acres is designated as the “homestead” and is allowed one house, and the rest is woodland that could be logged responsibly under the easement. Sheble doesn’t live at the farm currently but has tenants who farm there.

While she originally signed on to the easement without any real worries and without wanting more than one house on the property, Sheble said that life circumstances have left her in a tough position.

“Had I known I might really want to sell it 10 years later, I might have refrained,” she said. Now her tenants want to build a small house on the property for themselves and buy it from her, but the easement won’t allow a second house. Sheble has an understanding with the person currently living in the main house, though there aren’t any legal documents involved.

Jennifer Irving, the Sebasticook Regional Land Trust executive director at the time, spoke with the lawyer about the possibility of a variance, but changes in easements can’t “impact conservation qualities.”

Irving said this is why they try to have a lot of discussion before agreeing to an easement. “We don’t want to be the reason a choice is eliminated,” she said.

While Sheble said she is happy that the land won’t be subdivided further, she is frustrated that it is going to be more difficult to sell and wishes she had more options to give people interested in being stewards. She admits she may have gone into the process wearing “rose-tinted glasses” and didn’t think her situation would change as much as it has.

She likes the innovative ways younger people are living together, building separate houses on one property but sharing gardens and farmland for example, she said. That can no longer be done on her property, even though the 5 acres would be enough, she said.

PROTECTING THE LAND

There are a number of land trust organization throughout the state of Maine and the rest of the country. The Maine Farmland Trust, the only statewide organization, says its goal is to protect farmland and aid farmers. The cause for concern over farmland is partly a result of changing demographics, Ellen Sabina, MFT’s outreach director, said in an email.

“The ownership of up to 400,000 acres of our best farmland will be in transition within the decade, as many current farmers reach retirement age,” Sabina said. “A lot of that land could be lost to development unless it’s protected.”

Maine is considered the oldest state in the nation, not because it currently has the highest percentage of seniors, but because it has the highest median age of any state — 44.5, according to an estimate by the U.S. Census Bureau. This means that half of all Mainers are older than 44.5. The national average median age is 37.8.

Baby boomers are hitting retirement age in the next few years, and the farming industry isn’t safe from this trend. A large number of Maine’s farmers are in the 45-to-74 age group, according to 2012 data from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service.

As land changes hands, some say it’s more likely to be developed. An agricultural easement requires whoever buys the land to keep it the way it is — essentially, a land trust buys the developer’s rights to the property.

That’s how Deb Dutton and David Smith saved 260 acres in Unity that nearly had been lost.

After the area, made up of both hayfields and woodland, went up for sale, a developer bought it immediately to build 15 house lots. In 2007, the Maine Farmland Trust stepped in to negotiate with the developer and approached Dutton and Smith about stepping in as “conservation buyers,” Smith said.

The couple bought the property at full cost — which included extra money for the developer’s lost profits — and the Maine Farmland Trust, along with the Sebasticook Regional Land Trust, secured grant funding to pay them back by purchasing the developer’s rights. In the end, the couple saved some money from creating an easement, Smith said.

The process for them was quick, in part because there was “no question that it was endangered by development,” Dutton said, so securing grants took less time. Their participation was mostly just waiting.

Besides the cost savings, the couple decided to purchase the land, now called Woodsong Farm, to save something that they thought was a symbol of their town.

“We’ve been seeing a lot of prime farmland being carved up into house lots,” Smith said. “A big part of the character of Unity is farming, is its agriculture, its fields and views.”

Dutton and Smith’s easement also saved valuable community attractions. Part of the Hills to Sea Trail that runs through Unity, along with a snowmobile trail, goes through their woodland.

“I think it’s critically important for people to appreciate the open space we have and the community we have,” Smith said.

MILLIONS OF ACRES

Back in the late 1800s, Maine had 6.5 million acres of farmland. Today, Sabina said, the number has dropped to about 700,000 acres.

Of the lost acreage, about 1.3 million acres, or 22.4 percent, were developed.

Most of the lost farmland turned to forestland, especially in northern Maine, according to Walt Whitcomb, commissioner of the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry.

“The bigger conversion is simply abandoned farmland,” Whitcomb said in an interview. As Maine developed and farming became less and less profitable, trees filled in the fields.

For the state, Whitcomb said they have to focus on the “many pieces” of farming — meaning they have to try to help farmers survive. The department tries to help market local food and support farmers financially.

“One of our concerns is keeping people in business so individuals … want to keep farming,” he said.

The department does its part to help keep farming in Maine financially viable through marketing promotions, such as the recent “Get real Maine” promotions program, and pushes to export trendy products such as cheese. But ultimately, the choice is up to the consumers, Whitcomb said, and eating locally sourced food costs more money.

“It’s a constant effort to be in the marketplace,” he said. “We wouldn’t still be losing farmland to bushes if people were getting rich from farming.”

According to 2012 USDA Agricultural Census data, 3,148 of the 8,173 farms in Maine made $2,500 to $24,999 in sales. About another 3,000 made less than $2,500. Only 1,746 made $25,000 or more.

The average net cash income of a Maine farm in 2012 was $20,141, down from $20,609 in 2007.

While incomes for farmers don’t seem to be increasing, costs are still going up. In Maine in 2007, the average production expenses per farm were $60,680, according to USDA data. In 2012, costs had increased by more than $18,000 to $78,996.

However, Whitcomb said the data does show some positives. The value of crops increased by about 25 percent between 2007 and 2012, he said, so farmers don’t need as much acreage to turn a profit.

Still, getting people to buy local food from smaller farms is the difficult part of the equation, Whitcomb said.

“If you go to the market, it doesn’t look like there’s a shortage of food,” he said. Because of that, people aren’t conscious of the losing economics farmers face and the threat that poses to the country.

Increasing the amount of farmland in the state might not be good for the environment either, Whitcomb said. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the government paid people not to farm because land was sliding away because of Maine’s rocky and steep geography, he said. In the early 1800s and 1900s, “you could just see cleared land,” which wasn’t environmentally smart, he said, because of problems such as runoff.

However, the commissioner did say he sees some room to grow if farms can find ways to be profitable.

As of now, the state has organizations that, in certain areas, are “competing against each other to help farmers, and that’s a good thing,” he said.

FARMS FOREVER

The Sebasticook Regional Land Trust was founded with the mission to “conserve the working landscape” of the area, according to Irving, now a project manager at the land trust, which recognized that it had such a rich ecosystem of land around it in part because of the cultivation of the land by past farmers.

“We’re continuing the farmland tradition because it is a good stewardship move,” Irving said.

The process for placing an easement on a piece of farmland is typically long and laborious, she said. The organization likes to “spend a lot of time at the kitchen table” discussing the property owner’s visions for the farm and what the key parts of the land are to protect. For Sholz and the Albion Bread Farm, the process began in 2006 and ended in 2010.

Then, when an agreement is finally made, the Sebasticook Regional Land Trust sometimes go out to find funding through federal or statewide grants. Other times, farmers donate an easement to the land trust.

Putting an easement in place can cut down the selling value of the property, though not its taxable value, because it takes away a future buyer’s ability to build or develop the property — essentially, the land has less potential.

When Sholz conserved his property, it cut the value nearly in half, he said, which he got back when the land trust purchased the developer’s rights from him. The Sebasticook Regional Land Trust also provides the legal assistance necessary to create and maintain an easement.

Dutton and Smith, of Woodsong Farm, don’t see their property as having lost value from the easement, though.

Smith said there is some evidence that shows placing an easement on a piece of land doesn’t always hurt its selling price down the road. A lot of people like larger properties, he said.

After the land changes hands or the owner dies, the land trust is forever responsible for maintaining the easement, Irving said.

It’s possible that new landowners will make a violation, but if that happens the land trust can correct the problem. Irving said she doesn’t know of any case in which the Sebasticook Regional Land Trust failed to fix a violation.

Once an easement is placed on a property, it is nearly impossible to change, she said.

For Sholz, an easement was the right choice. He said he saw new farmers struggling to find land and realized that what he had was invaluable.

“This is something that can’t be replaced in any short or foreseeable amount of time,” he said.

Madeline St. Amour — 861-9239

mstamour@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @madelinestamour

Send questions/comments to the editors.